translated by Christina Schlögl

February 9, 2017 – where is the Joanneum? This question cannot be answered as easily as a clueless tourist during his or her first visit to beautiful Graz would think. The Joanneum is not located in one site but in 12(!).

A glance into a small part of the armoury, which is spread across several floors. Photo: © UMJ.

It starts with the armoury of the state (Landeszeughaus), a former collection of armour, rifles, canons, melee weapons and pole weapons (in plain language sabres, halberds and such stuff. By the way, if you should ever find yourself at the Joanneum, lost among all this “stuff”, you can still sound like an expert by using the German word for “stuff”, which is “Zeug”. Even though “Zeug” now simply means “things”, in Early Modern German, it was used to describe all sorts of equipment, one needed for the noble art of warfare. The change in meaning might be an indicator of people’s opinion on the matter…). Anyway, with 32,000 exhibits, this part of the Joanneum is the biggest preserved historic armoury in the world. And that is only a small part of the whole museum. There is also the Joanneumsviertel with the New Gallery and the natural history museum.

Ducal hat, ca. 1400, cast silver, forged, gilded; pearls in enamelled leaves, ermine and mouse weasel tail from 1766. KHS, Inv.-Nr. 12127, Photo: © UMJ.

At a distance of around 500 metres by foot, you will find the magnificent Palais Heberstein, where the historico-cultural objects are, including the famous Styrian ducal hat, which still crowns the Styrian coat of arms…

Charles II, Archduke of Austria. Taler-klippe 1586, Graz. From the Coin Cabinet of the Joanneum. Inv.-Nr. MK 55.075. Exhibition catalogue 78. Photo: © UMJ.

…and has been in coin effigies several times. The metal parts – especially the prominent prongs of the ducal hat, which are easily noticeable in the effigy – trace back to the times of Ernest, Duke of Austria (1377-1424), fourth son of Leopold III, who died at Sempach.

View on the museum of art. Photo: KW.

There is also the House of Art (Kunsthaus Graz), whose modern architecture cannot be overlooked among the cityscape. Not to forget, the Steirische Volkskundemuseum (Styrian Museum of Popular Art), which is located at the foot of the Schlossberg.

Eggenberg Palace. Photo: © UMC.

And we have not even come to the highlight, which is located in a beautiful park just outside of Graz on the edge of town. It is Eggenberg Palace. The Palace and the old town of Graz share the status of World Cultural Heritage.

RDR Friedrich III. (V.), 1439-1452-1493. Penny 1458 Graz. From the auction Auctiones AG 29 (2003), 1312.

Eggenberg Palace, as the name suggests, was built by the Eggenbergs, who could never be left out when talking of Austrian numismatics. Their rise to power goes back to Balthasar Eggenberger, who made his life’s fortune with coin minting – much to the annoyance of the general public. He reduced the silver content of the Graz pennies to such an extent, that it reduced their purchasing power dramatically. Or, as a Salzburg (!) chronicle from the year 1459 noted: “At that time, Emperor Frederick had a bad coin minted, which the people called Schinderling. (From the German verb “schinden”, which means avoiding to pay for something or trying to get the most out of something by letting other people do the work and not helping yourself.) This coin got lighter every day and that lasted until people did not want to accept it anymore, since it only consisted of copper. No one could buy a pair of shoes for 180 pennies!”

A glance into the first exhibition room. Photo: KW.

It is this very penny and the inflation it caused, which the first room of the exhibition of the Eggenberg Coin Cabinet is dedicated to. It is included in all guided tours of the palace, as no other exhibition works better to explain where all the money came from, which made the Eggenbergs so rich that they could join the game of big politics and finance the undertakings of Frederick III as his bankers.

RDR Friedrich III. (V.), 1439-1452-1493. Kreuzer 1458 Graz. From the auction Rauch 93 (2013), 2552.

As a beneficiary, the emperor did not protect the public against the coin forgery that was going on. Instead, in addition to the right to mint pennies, the bankers were granted the privilege to issue kreutzers that were equally low-quality in 1458. What happened then, is summarized by the chronicler Jakob Unrest as follows: “It was at that time, the mint masters and coin privilege holders became the great lords.”

Hans Ulrich von Eggenberg. Tenfoldducat 1629, Prague. From the Coin Cabinet of the Joanneum. Inv.-Nr. MK 3833. Exhibition catalogue 83. Photo: © UMJ.

The Eggenbergs stayed in business. Hans Ulrich (1568-1634) was part of the infamous Prager Münzkonsortiums (Prague coin consortium), which starter the Kipper and Wipper in 1622/3 in order to finance the war of Ferdinand II. While the economy of the Holy Roman Empire was failing, men like Hans Ulrich von Eggenberg, Albrecht Wallenstein or Karl von Lichtenstein made a fortune and were even honoured by the pope. Hans Ulrich received the barony Crumlaw in Southern Bohemia, and the title of imperial prince, which he celebrated by rebuilding Eggenberg Palace, the ancestral seat of his forefathers, into a proper palace. After the murder of Wallenstein, Hans Ulrich retreated to Graz and died shortly after.

Johann Anton von Eggenberg. Gnadenpfennig 1639. From the Coin Cabinet of the Joanneum Inv.-Nr. MK 43.749. Exhibition catalogue 84. Photo: © UMJ.

Let´s go back: The patriarch of the family is nothing more than a successful coin forger – albeit with imperial backing. Five generations later, the emperor sends his descendant to Rome in order to officially confirm the accession to the throne of the Pope. People were still talking about the wealth Johann Anton presented there, even decades later…

Johann Anton wanted to meet the standard of the old aristocracy. That included a bride that befitted his class. Margrave Christian of Brandenburg in Bayreuth and Kulmbach offered his oldest daughter. And even though she was protestant and, with her 30 years, somewhat old and practically without a dowry, she was the granddaughter of an elector after all. Virtually ideal! The gnadenpfennig with a weight of 31.28g, which we are showing here, was most probably issued on occasion of their wedding.

Johann Christian and Johann Seyfried von Eggenberg. Tenfold ducat 1652, Crumlaw.34.61 g. From the Coin Cabinet of the Joanneum. Inv.-Nr. MK 3853. Exhibition catalogue 85. Photo: © UMJ.

When Johann Anton von Eggenberg died, he was only 39 years old. He left two sons at the age of nine and five. And they started fighting, once they were of age. The younger son, Johann Seyfried, insisted on getting a part of the inheritance, even though his father had actually wanted to introduce primogeniture. Thus the rich Bohemian assets came to the older son, Johann Christian and Johann Seyfried became lord of the property in Styria and with that Eggenberg Palace, which he had decorated into a magnificent baroque palace with around 600 mural- and ceiling paintings in only 7 years.

The famous Planetary Room of Eggenberg Palace. Photo: KW.

The furnishing of Eggenberg Palace is one of the most impressive instances of baroque interior architecture. Looking at these paintings, one sinks into the baroque world of thought. Alchemy was not an exotic-deviant idea but instead it was well-known body of thought. Knowing about it which was part of the bon ton of the aristocracy. In the Planetary Room, the painting revolves around the seven alchemistic metals and the planets, which are associated with the seven great properties of the family and with the most important family members.

The Porcelain Cabinet. Photo: KW.

During a later restauration in the style of Rococo, three East-Asian cabinets were installed in Eggenberg Palace, two of which were equipped with precious porcelain…

Cabinet with silk painting. Photo: KW.

…while the other one is decorated with a Japanese folding screen that is cut into eight panels.

After the Eggenbergs had died out, Eggenberg Palace came to the Herbersteiners in 1774 and it stayed in their possession until it was sold back to the state of Styria in 1939. Therefore Eggenberg Palace is the site for the most important collection of the Joanneum, which includes the Coin Cabinet without a doubt.

Memorial for the archduke John of Austria in front of the town hall of Graz. Photo: KW

The archduke John of Austria (1782-1859), who is omnipresent in Styria, had founded the Joanneum as an “Innerösterreichisches Nationalmuseum” (domestic Austrian national museum) together with the status groups of Styria. “Domestic coins from all kinds of metal” were already named as one of the seven historic collections of the museum in the founding statutes.

A glance into the Coin Cabinet, where the treasures of Styrian numismatics are presented. Photo: KW.

Today, roughly 2,200 Styrian coins and medals are kept in the Coin Cabinet. It is an impressive number, which has accumulated, because coins have been systematically bought since the founding of the museum. Joseph Wartinger, who was director of the coin- and antiques cabinet from 1817 until 1850, wrote in his annual report from 1817 that “rare coins, especially Styrian coins of all kinds of metal should be bought or traded by the institute”. Which Coin Cabinet still invites collectors, when they want to sell (sic! not give away!) these coins, to “let the institute have them”.

Ferdinand II. Threefold taler 1625, Graz. From the Coin Cabinet of the Joanneum. Inv.-Nr. MK 2954. Exhibition catalogue 87. Photo: © UMJ.)

His successor, Carl Schmidt von Tavera (curator 1857-1860), somewhat limited the collecting activities. From now on, Roman, Greek and Styrian coins should be considered. On a small scale, coins from the Habsburg and Austrian territories should also be collected. Of course one would still accept foreign mints if they came as gifts.

Big magnifying glasses not only enable visitors to get a larger image of the coins in the vitrines, but they are also presented with additional information of a screen. Photo: KW.

Basically, collecting – and exhibiting – is still the same today. It is mostly Styrian coins that make up the exhibition…

Denarii and antoniniani from the treasure of Mürzzuschlag, lost after 241 AD, refound 1834. exhibition catalogue 54. Photo: © UMJ.

…and the precious treasures that are kept in the Coin Cabinet.

Karl Peitler in front of the entrance to the Coin Cabinet. Photo: KW.

Mag. Karl Peitler is the department head in charge of the Coin Cabinet and the archaeology section. He conceived the numismatic and archaeological exhibition that can currently be viewed at Eggenberg Palace.

The Most Holy Place, the actual Coin Cabinet. Photo: KW.

He guards the 70,000 numismatic objects…

Karl Peitler shows us a drawer with Styrian rarities. Photo: KW.

…which cause the Coin Cabinet of the Joanneum to be the second largest coin collection in Austria.

Decorations from the estate of John, Archduke of Austria. Photo: KW.

The collection does not only include coins and medals but also rare decorations, like these pieces from the estate of John, Archduke of Austria. In order to really appreciate this tray, one should know that a piece from the Order of the White Eagle (Russia), roughly from the same time, whose former owner was unknown, was sold for 160,000 without surcharge at an auction in 2013.

Workrooms of the numismatic department. Photo: KW.

Apart from having an extensive library…

A glance into the lecture room of the numismatic department. Photo, KW.

…the Coin Cabinet also has a big lecture room at hand, which is in regular use. Karl Peitler is very keen on building a bridge between research and collectors. Thus, he considers both activities to be important for the Coin Cabinet: scientific colloquia, the publication of the “Schild von Steier”, a specialist journal for archaeology and numismatics, and popular science lectures for collectors and friends of numismatics.

Deposit find from Schönberg near Niederwölz, 9th century BC. Photo: KW.

Oh, yes, one last tip. When you visit Eggenberg Palace, be sure to take a look at the archaeological collection. Not only because of its impressive hoards.

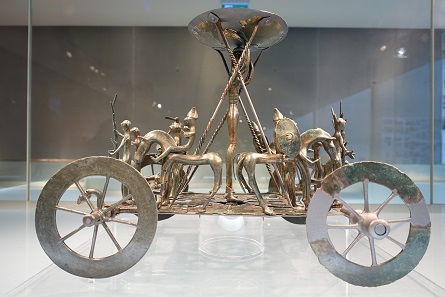

Cult wagon from Strettweg, 7th century BC. Inv. Nr. 2000. Photo: KW.

Highlights like the Celtic cult wagon from Strettweg…

Mask of Kleinklein. Inv. Nr. 10.723, 6001. Photo: KW.

…or the death mask of Kleinklein are simply unforgettable.

Let’s sum up. The Joanneum and Eggenberg Palace are not the kind of sight you visit on the go, because you are in Graz anyway. They themselves are enough reason to travel to Graz.

The best way to get more information, is of course the Homepage of the Joanneum.

The Coin Cabinet has its own homepage.

Shortly after the opening of the numismatic exhibition, Karl Peitner wrote his own article about it in CoinsWeekly.

If you would like to obtain “Schild von Steier”, you should visit the website of the publishing house Phoibos.

Graz tourism celebrates Eggenberg Palace as one of their top 10 sights. They have put together a short film on their website, which shows the baroque castle fin its best light.

By the way, in 2011, the Austrian Mint has honoured the 200 year anniversary of the Joanneum with its own coin.

Oh, and there are three coin dealers in Graz, who are members of the Verband der Oesterreichischen Münzhändler.