On January 31, 2019, auction house Künker will hold their Auction 316 in the context of the World Money Fair. One of its highlights is found in the “Russia” section. A complete set of Russian platinum coins from 1839 will be on offer. What is special about them is their origin. All three coins were once part of the Great Prince Georgy Mikhailovich Collection and the Emeryk Hutten-Czapski Collection.

Russia. Nicholas I, 1825-1855. 12 rubles platinum 1839, St. Petersburg. Featuring collector’s mark by Hutten-Czapski. NGC Grading (photo-certificate) PF 64 Cameo. Including expertise by Schiryakov & Co., Moscow. Proof, slightly touched. Estimate: 250,000 euros.

Three platinum coins

Between 1828 and 1845, die Russian government had more than 1.2 million platinum coins worth a total of 4,251,843 rubles minted from 14,665 kg of platinum. The idea was to define a reasonable purpose for the platinum that had been manufactured industrially since 1824. It was the Russian minister of finance, Georg von Cancrin, born in Hanau (Germany), who convinced Czar Nicholas I to grant permission on April 25, 1828 to have platinum coins to the value of 3 rubles minted. In 1829, coins to the value of 6 rubles were added. From September 1830 on, 12 rubles coins were also struck.

Russia. Nicholas I, 1825-1855. 6 rubles platinum 1839, St. Petersburg. Featuring collector’s mark by Hutten-Czapski. NGC Grading (photo-certificate) PF 64 Cameo. Including expertise by Schiryakov & Co., Moscow. Proof, miniscule signs of touch. Estimate: 150, 000 euros.

The production of the necessary alloy was extremely complicated back then. Due to its high melting point of 1,768 degrees, it was not possible to melt platinum as easily as gold (1,064 degrees) or silver (961,8 degrees). It had to be extracted chemically. The processing of the raw material, the so-called “platinum sponge”, into a blank required a lot of effort and took several days.

Russia. Nicholas I, 1825-1855. 3 rubles platinum 1839, St. Petersburg. Featuring collector’s mark by Hutten-Czapski. NGC Grading (photo-certificate) PF 64 Cameo. Including expertise by Schiryakov & Co., Moscow. Proof, slightly touched. Estimate: 100.000 euros.

Despite the effort that was put into their production, the coins were not popular among the Russian population. It was much too easy to confuse them with silver coins. As platinum was rated higher in other countries, many of the coins found their way across the Russian border. Hence, the czar prohibited the export of platinum coins in 1845 and ended their production in June of the same year.

75-77% of the coins were then collected, exchanged for gold and silver coins, and melted. That is the reason why platinum rubles are so rare nowadays, especially the ones in the perfect condition Künker can offer in this auction.

In this context, the year 1839 is particularly rare. According to the mint’s records, only two complete sets of this year of issue were struck. However, it is said that novodels were later made using the old dies. Dr. Igor Shiryakov, the director of the coin cabinet at the State Historical Museum in Moscow, believes that the pieces offered in Künker Auction 316 are such novodels. This practice was abandoned in 1890, by the way – on the orders of Georgy Mikhailovich of all people.

Great Prince Georgy Mikhailovich. Photo: Library of Congress. Digital ID ggbain. 16954.

The collector Georgy Mikhailovich

The Russian Great Prince Georgy Mikhailovich is probably one of the most renowned collectors of Russian coins. Not only because he compiled an important collection, but also because, as the grandson of Czar Nicholas I, he was part of the Romanov family.

Georgy Mikhailovich was born on August 23, 1863. His father, Great Prince Michael Nikolaevich, held the office of Governor General of Caucasia at the time. Georgy’s mother was from Germany. Cecile, who adopted the name Olga Feodorovna in Russia, was from Baden and had become famous because of her sharp tongue and iron hand.

Hence, young Georgy and his brothers were all raised in a spartan manner. He slept on a cot, had to wake up at 6:00 in the morning, and take cold baths. Tutoring lessons were held from 8:00 am to 11:00 am and 2:00 pm to 6:00 pm. Anyone who miscalculated something, had to kneel for an hour. Anyone who misspelled a word, was not allowed to have dessert.

A meeting of the Romanov family: f. l. t. r.: Czar Nicholas II, Great Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich, Great Duchess Maria Pavlovna, Great Prince Sergei Alexandrovich, Great Prince Michael Nikolaevich, Great Prince Georgy Mikhailovich, and Great Prince Sergei Mikhailovich. Photo from the 1890s.

Was Georgy Mikhailovich upset about the fact that a severe leg injury limited his fitness? In any way, he was not entrusted with administrative or military tasks. Instead, he was assigned to work in the field of cultural policies. Luckily, one might say. He is more widely known nowadays – at least in the world of numismatics – than all other great princes.

In 1895, Czar Nicholas II made him director of the newly established Russian Museum. This was very much in accordance with what Georgy Mikhailovich was interested in. He had shown interest in numismatics as a 14-year-old already.

The Mikhailovich Collection

As was his contemporary King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy, Georgy Mikhailovich was an important numismatist. He wrote ten numismatic works, including his catalog of coins of the Russian Empire 1725-1891 consisting of 12 volumes which, to this day, is one of the most important works on Russian numismatics.

On the side, Georgy Mikhailovich also compiled arguably the most significant collection of Russian coins and medals ever to have existed. They say that at least one specimen of every coin type that ever circulated in Russia found its way into his collection. In 1909, he decided to move his own collection to the Russian Museum for research purposes.

And then the revolution began. Georgy Mikhailovich was taken captive on April 3, 1918 and shot alongside his brother on January 28, 1919. At that point, his coin collection had already been packed in boxes and taken outside of the country, so that his window could manage it. The exact circumstances of the relocation cannot be reconstructed anymore. Today, large parts of the collection are kept at the Smithsonian Institution.

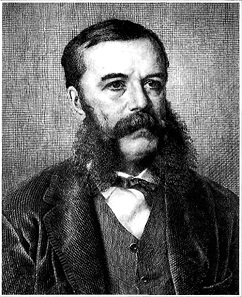

A portrait of Emeryk Hutten-Czapski (1828-1896).

The Hutten-Czapski Collection

The Mikhailovich Collection is also important because the great prince managed to acquire the Russian coins of Count (and numismatist) Emeryk Hutten-Czapski. The Polish nobleman built a career in the Russian administration. At that time, he had compiled an impressive collection of extremely rare Russian coins, which he sold to Georgy Mikhailovich between 1882 and 1884 in order to be able to expand his own specialized field of collection Poland.

In 1894, Hutten-Czapski moved from St. Petersburg to Krakow, which was also called the Polish Athens back then. His collection can still be viewed there today. His widow gave the collection to the city in 1896. That is the reason why the numismatic museum of Krakow is called “Emeryk-Hutten-Czapski-Museum”.

The three objects offered at Künker are not only extraordinary examples of a very special episode of Russian monetary history. They are also a testimony of the work of two outstanding numismatists: Great Prince Georgy Mikhailovich and Count Emeryk Hutten-Czapski.

You can find the auction catalog on the Künker website.