On August 5, 1850, Queen Victoria signed a law allowing extensive areas around Melbourne to become independent from the Australian province of New South Wales. When this independence took effect on July 1, 1851, a mere 77,000 people were living on an area of 240,000 square kilometers.

Gold nugget at a weight of over 150 g (= approx. 5 oz.) from a gold mine near Ballarat, Victoria. Photo: Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com / cc-by-sa 3.0.

How do you populate an empty province?

77,000 people really can’t be called a state. They needed more. But how do you populate an empty province? In the middle of the 19th century, every local politician had an impressive example in mind: The California gold rush had turned a deserted territory into a fully functioning federal state within three years. Australia wanted to imitate that. And the fact that there was gold in Victoria had been known to the locals for a while.

Thus, a group of important businessmen and politicians from Melbourne founded the Gold Discovery Committee. It promised a reward of 200 English pounds to everyone who found gold within a radius of 200 miles. Hundreds of prospectors then set out to search for it – and found some of the richest goldfields of the world.

And these attracted thousands of people. Whereas the 77,000 inhabitants of Victoria in 1851 had equaled 18% of all of Australia’s people, the province counted 538,628 people ten years later, making up 47% of Australian inhabitants. Municipalities like Melbourne, Castlemaine and Ballarat were booming. And in 1854, the Gold Discovery Committee could proudly declare: “The discovery of the Victorian Goldfields has converted a remote dependency into a country of worldwide fame; it has attracted a population, extraordinary in number, with unprecedented rapidity; it has enhanced the value of property to an enormous extent; it has made this the richest country in the world; and, in less than three years, it has done for this colony the work of an age, and made its impulses felt in the most distant regions of the earth.”

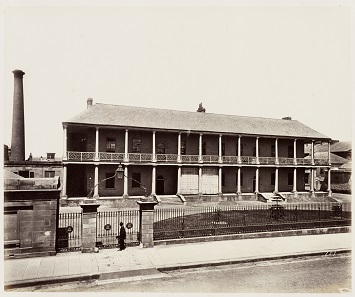

The mint in Sydney. Photo from 1872. State Library of New South Wales, PXD 524.

A mint for Australia

At this point, the British government had long since set the monetary course. Since 1851, the parliament of New South Wales had been sending petitions to London asking for the establishment of their own mint.

Gold in the Sydney mint. State Library of New South Wales, IE1798510.

The plentiful gold – in 1852 alone, 174 tons of gold had been mined in Victoria, at the time worth about 14 million pounds – made it quite annoying for the Australian economy, which suffered from an extreme shortage of cash, that the raw material had to be sent around half the globe to England in order to be refined and minted.

The Sydney mint, at the time on the outskirts of the city. State Library New South Wales, IE1771401.

As early as August 1853, the British government had decided to send equipment and staff to Sydney in order to establish a mint there. Edward Wolstenholme Ward (1823-1890) was appointed deputy-master.

He decided to set up the mint in an empty building on the outskirts of the city, which had originally been built as a hospital. After all, gold would be refined there in large quantities, and because of the fire hazard, it made sense to be working outside of town.

The first coins were ready on June 23, 1855. In October of the following year, the mint was already able to strike 14,000 ounces of gold in a week!

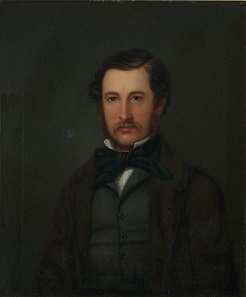

Capt. E. Ward. Oil painting by J. Anderson, Sydney 1859. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales IE3218437.

The director of the mint: Edward Wolstenholme Ward

The director of the Sydney mint, Captain Edward Wolstenholme Ward, was a typical specimen of British colonialism. He was born in Calcutta, India, to a Bengali civil servant. He received his education at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich and at the University of Chatham, where he studied engineering and architecture. He worked on Bermuda before returning to Great Britain. After further education at the London Royal School of Mines, he started his career at the Royal Mint.

It had been his assessment that convinced the British government to establish an Australian mint. Thus, it was only logical to make him the director right away. He was given a couple of highly competent people to accompany him, like the economist William Stanley Jevons, who would later become well-known and whose name lives on in the Jevons paradox.

However, we are much more interested in how Jevons characterized his boss. He described him as “a military man, very determined and arbitrary”, who was “generally civil and attentive, but very distant”.

Besides being a pioneer of the Australian sport cricket, Ward became one of the most important representatives of the British administration in Australia. He would also set up the Melbourne branch of the Royal Mint, which opened in 1872, before retiring in 1876. By that time, he had remarkable assets. His Australian estate was valued at 16,890 pounds. On top of that, he owned a villa in the French city of Cannes, where he spent his retirement and passed away in 1890.

Australia. Victoria, 1837-1901. Pattern for the Sovereign 1855, London. Proof. PCGS PR 65 CAMEO. Estimated price: 125,000 euros. From Künker auction 316 (January 31, 2019), No. 869.

Patterns for the sovereigns

In 1853, it had been decided that a mint would be established in Sydney. In the same year, the London mint produced the first patterns for sovereigns and half sovereigns, with the old portrait of Queen Victoria by William Wyon.

His son, Leonard Charles Wyon, who had taken over his father’s position at the Royal Mint in 1851, created the portrait for our pattern, of which only three specimen exist in private ownership. It will be offered at the upcoming Künker auction on January 31, 2019, at an estimated price of 125,000 euros.

In the years 1853, 1855 and 1856, patterns with both obverse types were issued. They were all struck with the same reverse die which would become the model for Australian sovereigns between 1857 and 1870, showing a wreath of laurels surrounding the word AUSTRALIA.

New South Wales. 5 Shillings (Holey Dollar) 1813. Estimated price: 100,000 euros. From Künker auction 316 (January 31, 2019), No. 881.

New South Wales. 15 Pence (Dump) 1813. Estimated price: 30,000 euros. From Künker auction 316 (January 31, 2019), No. 882.

Above that, we see a crown surprisingly similar to the one that was featured on the dumps in circulation in New South Wales at the beginning of the 19th century.

Originally, the coins were exclusively designated for New South Wales. But in 1857, the British Treasury declared the coins from the Sydney mint to be legal tender in all colonies of Australasia. Very much to the annoyance of the local politicians of Melbourne and Adelaide, who were hoping to be allowed to set up their own branches of the Royal Mint in their respective towns. Subsequently, someone spread the rumor that the sovereigns from Sydney were made of low-quality gold.

The following inspection then revealed that, on the contrary, the Australian sovereigns contained a higher percentage of gold than the English ones. By that time, sovereigns from Sydney were already in circulation in Newfoundland and India. Thus, it was only consistent that, in February of 1866, they were given the status of legal tender throughout the United Kingdom as well.

In 1926, the Sydney mint was closed. Today, it is registered in the New South Wales State Heritage Register and can be visited as one of the Living Museums.

Many pictures from the minting facilities are available on the website of the Sydney Mint Museum.

You can learn much on Australian numismatics on this website where you will also find a short summary of the Sydney Mint’s history.

And here you may read a biography of the Sydney Mint’s first deputy-master.

Go to the Künker website if you want to browse through the online auction catalogue.