by courtesy of the Berlin Coin Cabinet

on the occasion of its exhibit “Gold Giants”

Caracalla (reign A. D. 211–217) is the only one of Roman emperors who is represented on coins in a special way and personally related to the figure of Alexander. Apart from two bronze coins from Caesarea in Cappadocia and Heliopolis in modern Lebanon, which show the cuirassed bust of the emperor with a depiction of Alexander as emblem on Caracalla’s shield, only the Berlin Abukir medallion (and the specimen Dressel S which is identical in regard to the motive but differs in the die) represents the emperor in such a programmatic way.

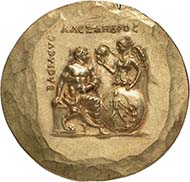

Caracalla, Gold medallion from Abukir, 1st half of the 3rd cent. A. D. Gold, 65.12 g, 48 mm, 1 h. Berlin Coin Cabinet, from the Abukir find, Berlin Coin Cabinet object no. 18200021.

This special Berlin Abukir medallion, therefore, is a magnificent visualization in gold of the historically attested Alexandermania of this ruler who wanted to align himself with his famous model in his actions, demeanour and appearance. Both the mentioned civic coins and the Abukir medallion are a reaction to the Imperial preference; the gold medallions which were created after the death of Caracalla have to be seen in the light of his role as alleged ancestor of the then reigning Emperors Elagabalus and Severus Alexander.

The appearance of Caracalla with the emotive form of the bust aims at expressing momentum and power. Models for this can be found already in the coinage of the Bactrian rulers in Hellenistic times and likewise in many portrait busts of Caracalla and his father in the civic coins of the provinces.

The depiction on the reverse of the gold medallion is equally spectacular. Alexander is depicted with a shield showing a famous scene of the Trojan War: the Queen of the Amazons, Penthesilea, is being killed by the Greek hero Achilles. Hence, the reverse (like Dressel C) depicts a shield Alexander himself had worn and not, as on the obverse, a shield with the image of Alexander in the hand of the emperor. We know, however, that Alexander had visited Troy and the tomb of Achilles, and that he had changed his own weapons for ones from the Sanctuary of Athena. That ›sacred shield‹ was to be carried in front of him in battle from then on. Years later, it indeed saved the King’s life.

How important this motive was in antiquity can be discerned from the fact that this special shield representation likewise appears on late antique contorniates. The motive’s history, however, was not concluded by that: when the so-called Tomb of Philipp was discovered in 1977 in Vergina a chryselephantine shield was found which depicted precisely this scene of the Amazon Queen being killed in battle.

This gold giant can be viewed in the exhibit of the Berlin Coin Cabinet bearing the same title. For more information click here.