translated by Christina Schlögl

In the first part, we told you why Erasmus of Rotterdam had medals with his portrait made and that these medals are still on display at the Historisches Museum Basel. That is the case because he designated the Basel citizen Bonifacius Amerbach as his heir and executor of the estate.

Bonifacius Amerbach. Painting by Hans Holbein Junior. Kunstmuseum Basel. Source: Wikipedia.

Memorabilia

Bonifacius Amerbach was a loyal executor. He sent bequests to the designated heirs, he administered the fortune of Erasmus worth 5,000 guilders, and he used it to pay the annual support for the poor and the grants for students. But he also defended himself against the illegitimate claims of everyone Erasmus had not remembered in his will. And he especially tended to the objects he had inherited himself after Erasmus’ death.

Erasmus-chest. Basel, 1539 (dated). 1870.911. Historisches Museum Basel, Photo: P. Portner.

He had a new chest made for them, which is part of the permanent exhibition at the Historisches Museum Basel. It was specifically made to store the estate of Erasmus. This is already expressed by the design of this gorgeous piece. At the very left, we can see Erasmus’ portrait in a medallion. There are three more busts in similar medallions, which do not have any notations but can be identified as the big scholars of the Greeks (Aristotle), the Hebrews (Salomon) and the Romans (Virgil). There is a matching Latin inscription: For myself and in memory of the greatest in the circle of scholars, I had this made.

Was Erasmus a collector?

We know for sure that Erasmus owned ancient coins: He had a gold stater of Koson, an aureus of Trajan and a solidus of Gratian. But is this enough to call Erasmus a collector of ancient coins? Probably not. He had gotten these coins more or less coincidentally as gifts and he kept them as valuable possessions. Basilius Amerbach however was more than willing to systematically buy objects from his deceased friend’s estate. Thus he paid Aurelius Erasmius Froben two guilders and a table knife, because it had “belonged to D. D. Erasmj”.

Covered cup, made by Jakob Stampfer (1505/6-1579), Zurich ca. 1550/1552. © Historisches Museum Basel. 1882.103. Historisches Museum Basel, Photo: P. Portner.

The collector

But this was not all, Bonifacius Amerbach accumulated. He bought beautiful, precious objects like the marvellous covered globe for 124 guilders in the year 1555, made by Jakob Stampfer, …

Taler of the League of God’s House n.y. (1565). Mint master Jakob Stampfer. From sale LHS 94 (2005), 3617.

… whom most coin collectors will rather know as the artist who designed the dies for the most beautiful coins of Switzerland.

Unicorn-relief. Oberrhein (?), ca. 1500. Walrus tooth. 1884.142. Historisches Museum Basel, Photo: P. Portner.

He was also fascinated by things, we would probably categorise as curiosities, like a matchbox-sized, carved piece of a walrus tooth, which in the 17th century was thought to be the magical tooth of a unicorn. This piece was listed in Bonifacius Amerbach’s coin index in 1552: “And a horn of a unicorn. cost 10 batzen.” This brings us to the coin collection of Bonifacius Amerbach. He possessed more than 252 coins total: 103 original and 6 casts of ancient coins of non-precious metal, 81 real silver, 10 gold and 50 “new” pieces.

Cabinet of curiosities

This was nothing, compared to what Basilius Amerbach, the third child and the only son of Bonifacius would gather later on. Just to name one example, the inventory of his prints mentions around 4,000 woodcuts, copper engravings and illustrated books. And that was only one of the many fields Basilius was interested in. Just like his father, he was professor for jurisprudence at the University of Basel. In the span of three weeks, at less than thirty years old, he lost his wife in childbed, the son she had just birthed and his own beloved father. It was a tragic break in Amerbach’s life. He retreated to his study, renounced domestic bliss and tried to find comfort in the well-organised world of his constantly growing collection.

He took it to his house, called “zum Kaiserstuhl” (“at the emperor’s seat”), which was located in Kleinbasel at the Rheingasse. When the rooms he called “mine Stuben” or “studierstuben” (“my study”), were not big enough anymore, he built his own cabinet, the “nüwe Cammer” (“new chamber”) to optimally store the objects. It was not a princely chamber and not meant for visitors, but a middle-class-practical one, which is attested for by a small coin cabinet, the only piece of furniture we still have today.

Coin box of Basilius Amerbach. Basel, ca. 1578. 1908.16. Historisches Museum Basel, Photo: P. Portner.

Amerbach’s coin cabinet

In the centre of the room, on a base, there was Amerbachs’s coin box, free and approachable from all sides. The finely worked drawers that could be pulled out of the box from every side are veneered and protected by Nürnberg locks. The box had enough room for 3,870 coins, medals and other objects, Basilius collected especially during the last years of his life. The drawers on the right contained the Greek and Roman coins, stored in chronological order. In the back, Amerbach kept the medals. On the left, there were rarities, gold- and silver coins, pearl works, gems, cameos, cut and uncut stones and everything else that was small and remarkable.

Three ancient statues were at the front, only two of which survived. There was a Venus at the centre. Amerbach bought it between 1576 and 1578 of Demoulin de Rochfort. At her right is Mercury, whose origin is unknown. There was a statue of Jupiter in the remaining, nowadays empty compartment, a gift by the Basel doctor Theodor Zwinger Amerbach.

This small piece of furniture is one of the oldest coin cabinets that have been preserved until today. And it is almost a miracle that its contents were not scattered across the lands, but are instead still on display in the different museums of Basel.

The oldest museum in Europe

n 1591 Basilius Amerbach died without a son. He left his entire estate to the son of his sister, Ludwig Iselin-Ryhiner. He and his son kept the collection without adding anything to it, but also without taking anything from it. But when Basilius Iselin died in 1648, the last male offspring of the family was gone. And immediately afterward, a legal battle about his estate started and the Basel government heavily interfered.

Incidentally, in 1648 the Basel governor Johann Rudolf Wettstein had asserted the confederation’s disengagement from the Holy Roman Empire in the Treaty of Westphalia. And this entailed an enforced self-image of the Basel bourgeoisie. People wanted to catch up with the other princely houses, which were so proud of their collections. After all, there were collections within the city walls which could compare to some of the princely collections…

Despite the voices that would rather have alienated everything, Wettstein advocated for sustaining the original ensemble: “I would greatly regret it if the Greeks, not to say the Goths should wrest this palladium from us. We will lose it disreputably, whether people will say we lost it for want of money or out of disregard for such valuable objects, which were gathered with unbelievable enthusiasm and effort by the most exceptional men, one and a half centuries ago. What to do? Please give me some advice, dear friend.” That is what Wettstein wrote in a letter from 1 March 1650.

But who should actually buy the expensive collection? No one could be found in Basel, so that Wettstein’s son asked around in Schaffhausen and Zurich, to prevent Amerbach’s cabinet from leaving the country. In the end, it was to be feared that Matthäus Merian’s (1593-1654) account in his Topographia Helvetiae, which was published in 1654, might soon no longer be accurate: “… deß Viti Amerbachij Hauß / darinn ein ansehenlicher Schatz von allerley alten Müntzen / Kunst vnd Rariteten / zu sehen.” (“… the house of Vitus Amerbach, where one can see an extraordinary treasure of old coins, art and rarities”)

But it was only when an Amsterdam businessman made a concrete offer of 9,500 reichstalers that the council decided to take action. On 20 November 1661, they decided to buy the collection from the heirs for 9,000 reichstalers – payable at three annual rates.

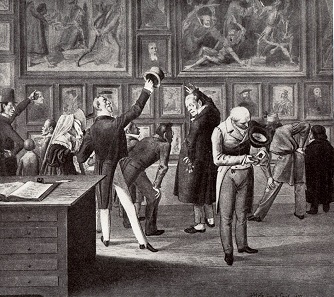

Pedell Scholer explains objects to visitors at the official Basel art collection on the foyer of the des Haus zur Mücke. Copper engraving 1837. Source: Wikipedia.

Since 1671, the collection was on display at the Haus zur Mücke, near the Münsterplatz. Initially it was only open once a week, namely on Thursday afternoon. Today, the people in Basel are proud that this was the first publicly accessible collection of a body politic.

Historisches Museum Basel. Coin cabinet. Historisches Museum Basel, Photo: Ph. Emmel.

And yes, there also was a “Cabinet d’Erasme”, where one could see the seal ring and other precious objects from the estate of the great humanist, just like at the permanent exhibit of the Historisches Museum Basel.

Historisches Museum Basel. The great art chamber. Historisches Museum Basel, Photo: Ph. Emmel.

It is well worth seeing, this permanent exhibit with the beautiful name “Wege zur Welterkenntnis” (“Ways to the perception of the world”), which does not only feature the story of the Basel collectors Erasmus of Rotterdam and Basilius Amerbach, but also the stories of Remigius Faesch, Felix Platter and many others. Next time you go to Basel, definitely pay a visit to the Historisches Museum Basel. The permanent exhibition of the coin cabinet, too, is worth one or two hours of attentive study.

You will find the first part of the article here.

The website of the Historisches Museums Basel can be found here.