by Andreas Udo Fitzel

Around 1590, a boy was born in Lower Bavaria whose baptismal name was “Johann Hameran Hermannskircher“. His last name already indicates that his family originated from the small hamlet Hermannskirche near Landshut. He probably grew up in Abensberg, south-west of Regensburg, where his father worked as court procurator.

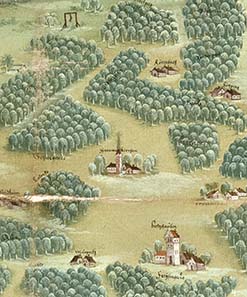

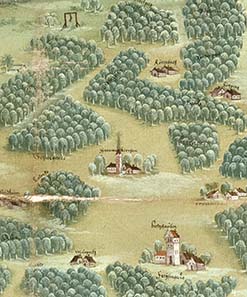

Hermannskirchen (in the middle of the picture) near Landshut on a map from 1584.

In 1604, Johann was sent to Munich to receive training as a goldsmith. His teacher was the influential gold smith master Gerhard Lindenburger whose workshop was located in the Dienersgasse near the Marienplatz. His training ended in 1610, but Johann couldn’t stay in Munich for long. After a quarrel over a young lady, Johann and his opponent had a duel. Johann suffered a heavy injury on his forehead and subsequently killed his rival. As a result, the young gold smith had to escape. Over the Alps he went first to Venice – after that, there is barely anything on record about him.

Saint Peter’s Square in Rome around 1710.

In 1615, Johann appears again in Rome. The Eternal City with its 100,000 inhabitants had only recently arrived in “Baroque times” (which, after all, had been “invented” there) and the place was overrun by artists, architects and artisans…

Johann got himself an appointment with a Roman gold smith. He fell in love with his boss’ daughter and married her in 1619. Already in 1620, he was born a son called Albert (Alberto).

Johann moved into a small house in the “Via del Pellegrino”. Before long, his middle name, “Hameran”, became the new family name: Hamerani.

Possibly through his father in law, the young Bavarian soon gained access to commissioned work for the Papal Court. Johann likewise worked in the Papal Mint as coin engraver where soon his colleagues nicknamed him: “il sottile” – fuss-pot…

His wife died around 1632. In 1635, Johann married a second time. In 1644, Johann was in Livorno on official business where death befell him.

Clement IX. Medal 1669 by Alberto Hamerani on the redesigned Ponte Sant’Angelo.

Johann’s son Alberto followed in his father’s footsteps. He made the medal dies which are the first ones preserved of the Hamerani family (since 1647). He moved into a house with additional workshop in the “Via dei Coronari” which he and his descendants after him populated for roughly 100 years.

Portrait of Giovanni Martino Hamerani from 1705.

With Alberto’s son the family slowly moved up the ladder to the highest circles in Roman society:

Giovanni Martino Hamerani was perhaps the most famous member of the family. Already during his lifetime, he was considered a magnificent artist who produced extraordinary coins and medals.

Innocent XI. Scudo 1676 by Giovanni Martino Hamerani.

The grandson of the Bavarian gold smith was appointed several high offices. In 1679, he was appointed medallist of the Papal Mint. Eventually, Giovanni Martino Hamerani became a close confidant and friend of Pope Clement XI.

Clement X. Medal 1673 by Giovanni Martino Hamerani on the grain supply to Rome.

The medals Giovanni created depict political, cultural and secular events and hence are unique testimonies not only of the Roman, but the entire European high Baroque.

Giovanni Martino had three skilled children who followed him in the art of die cutting: his daughter Beatrice could only create a few medals before she passed away at the age of 29, only a year after she had married. His son Ottone wanted to become a drawer and painter at first, but he reconsidered and produced medal stamps. In 1734, he was appointed “Master of the Papal Mint for Life”.

Clement XI. Medal from 1720 by Ermenegildo Hamerani on the enlargement of the University of Bologna.

The third son of Giovanni, Ermenegildo, was artistically almost as skilled as his father. The influential art expert Cardinal Alessandro Albani referred to him once as “the most talented man in Italy…”

For many years, the brothers Ottone and Ermenegildo Hamerani held a sort of monopoly position at the Papal Mint in the 18th century. Ermengildo was even “on loan” once to the Viceroy of Sicily who had transported him to Palermo by ship …

At the end of the 18th century, a certain Johann Wolfgang von Goethe visited Rome during his “Italian Journey” and came to appreciate the medals of the Hamerani. Later, Goethe had a collection of Hamerani medals assembled by Ferdinando Hamerani (the son of Ottone)…

The last member of the Hamerani family was Giovanni (“Giovanni III“, Ferdinando’s son). He lived in turbulent times. The Papal States collapsed and Napoleon seized the Eternal City which nevertheless outlived him. Giovanni continued to create coins and medals for the Popes until about 1810.

He was the last representative of the Hamerani family and died in 1846. His epitaph is preserved until the present day in the church “San Carlo ai Catinari“. It was donated by his daughter Maria Veronica whose story is buried in the dungeons of history.

Anyone interested in the intriguing history of the Hamerani family is kindly asked to have a look at a booklet of this article’s author. It can be ordered on the internet for 10 Euros with additional postage. To write an email to place your order, please click here.