by courtesy of the IBSCC

Part 4: Transfer die forgeries

Fakes coming from transfer dies are so dangerous, because these fakes have neither the characteristics of casts nor the characteristics of coins that have been struck with newly cut dies. You neither can recognize them by looking for casting holes, nor by comparing the style with a surely original coin. You have to apply a different method in order to detect transfer dies: the die study, the comparison of all known specimens that were struck with the same die. Doing a die study is a hard and lengthy business, but it is no witchcraft. You will need a good library containing as many auction catalogues as possible and you have to spend a lot of time in order to collect as many specimens of the same die as the questioned piece as possible. The die studies that have been done by scholars mainly for Greek cities are useful, but they are not sufficient, since many do not include the coins that have been recently on the market; yet those pieces, especially, are very important for discovering the truth. As the fake that was made by a transfer die must have the same characteristics as its “mother piece”, it becomes possible to detect these fakes as soon as there is known either a brother or the mother. And as most counterfeiters do not produce only one fake, but a series, detection of this special group of fakes is possible. These explanations sound rather theoretical: here is the example.

Fig. 1: Forgery of a solidus of Basil I.

Fig. 1 – unfortunately a very poor photo – shows a solidus of the Byzantine emperor Basil I, who ruled from 867 to 886. This very piece was sold at an auction sale held in London, and before it came to the IBSCC there had been a long discussion between experts over whether this piece was fake or genuine. It was obvious that the coin was struck. And on first sight our solidus did not differ from the style of solidi of the same time.

A die study was done which is the lengthiest method we have to detect forgeries. All known coins from the same type have to be collected.

Concerning Basil it was very simple for the IBSCC. We knew a collector scholar who has published in the meantime a study of the Byzantine gold coins minted during the 9th century. At that point the die-study was already nearly finished. Therefore the experts could refer to his exhaustive and up-to-date die-study including all solidi of Basil of this very type that had been on the market until now.

Fig. 2: Detail from the die scheme the scholar had made for the gold coinage of Basil I.

Fig. 3: Forgery of a solidus of Basil I offered in a US auction sale.

Fig. 2 shows the part of the material that was die-identical with the questioned piece. There were two other die-identical coins that are not shown here in this figure. Illustrated is one coin that is now in the Dumbarton Oaks collection and was sold in 1960 at Numismatic Fine Arts; the other piece was sold at Bonham’s in London in 1981. The collector could also supply photos of a coin from the ANS and another coin that was sold in the States in 1998 (fig. 3).

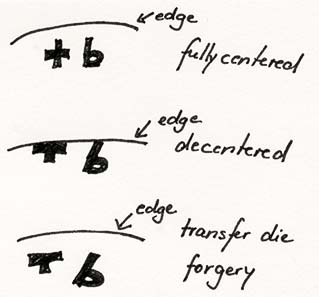

Fig. 4: Drawing of the change in the obverse legend that has caused the conclusion that the coin must be a forgery.

When we compare the obverses of the two coins (fig. 2) carefully with the questioned coin (fig. 1), we will see that the coins are from the same die, but they differ in an essential detail at the left side of the obverses. On the left centered piece that has been known since 1960 you will see clearly the beginning of the inscription: You will recognize a cross. If you look to our coin (fig. 1) which is also well centered, you will not find this cross, you will see the letter T. How could something like that happen?

There is a simple explanation. The right piece, which is a little bit off-center on the left part of the obverse, was abused by a counterfeiter to make a cast which was transformed into a die. Because of the off centering the cross at the beginning of the legend looked like a T. And on all products from the new die you now have the T, not the cross!

Based on this examination we could spot another fake that had not been questioned until then, the fifth piece that was part of the die study, which came to the market approximately at the same time as the IBSCC piece (fig. 3).

Unfortunately counterfeiters have tried to fool coin collectors as long as coin collecting exists. But on the other hand there have always been collectors who were clever enough to decide whether the coin offered was genuine or not. Learning to detect forgeries is no witchcraft, but needs a lot of experience. And those who want to collect not only coins but also experience have to accept that they sometimes will pay dearly for their wisdom and that they sometimes will find out about a coin that it is fake after having bought it. The only possibility to avoid learning about fake coins in the hard way is to buy at a coin dealer who guarantees the authenticity of the coins he sold. Sometimes a coin may be more expensive at the specialized dealer as it is on the Internet. Therefore those who like to gamble and those who think to have enough knowledge to detect all fakes themselves should not hesitate to buy there. Others should think about where they buy, before they buy.

| IBSCC is the abbreviation for the International Bureau for the Suppression of Counterfeit Coins. It was founded in 1975 by the the International Association of Professional Numismatists (IAPN), a non profit organization of the world’s leading professional numismatic firms with 112 members from 23 countries. IAPN members unconditionally guarantee the authenticity of the coins they sell. |