If you think that the Thirty Years’ War was a German affair, you are wrong. Germany was just the battlefield on which the rulers of Spain, France, Denmark and Sweden pursued their ambitions. An international front was formed at the Rhine. The Protestants and Catholic France stood on one side, and the Catholics around the Habsburg emperor and the Spanish on the other. It was all about the Netherlands. Those who controlled the Rhine were able to use or block the Spanish supply line between northern Italy and the Netherlands.

The envoys of the German states were merely tolerated spectators at the negotiations leading to the Peace of Westphalia. The fundamental decisions were made by the French, Swedish, Spanish, Dutch and imperial envoys. And it was they who decided that, after 30 years of war, Germany finally had a prospect of peace, and that the 80 Years’ War waged by the Netherlands against Spain was thus over, too.

The Interests of William II of Orange

Someone was not at all happy about the peace: the young and dynamic Stadtholder of the Netherlands, William II of Orange. However, when he took over the reign from his father on 14 March 1647 at the age of 21, there was nothing he could do despite all his efforts. The Netherlands signed the Peace of Westphalia. This was annoying for him. After all, he was married to a Stuart whose brother would have been the English king if Cromwell had not had Charles I executed. William needed soldiers in order to enforce his dynastic interests against Cromwell and Spain – but now, due to the peace treaty, the Netherlands wanted to reduce the size of his army and their tax payments.

William II refused to accept that and took violent action against the city of Amsterdam, where his loudest opponents resided. He had them imprisoned and ordered an attack on the city. Although the attack failed, the city fathers gave in: they preferred to fund William’s army than to engage in an even more costly conflict with him that would have been detrimental to trade.

Thus, there would have probably been a new season of the Eighty Years’ War against Spain had William II not been infected with smallpox. He died on 6 November 1650.

Sebastian Dadler’s Medal Commemorating the Death of William II

We do not know who commissioned the medalist Sebastian Dadler, who lived in Hamburg at the time, to create a medal that interpreted the death of William II as the fortunate intervention of a divine power. But we do know that there was a large Dutch community in Hamburg and that Hamburg had close trade ties with Amsterdam. Hamburg merchants, just like their Amsterdam counterparts, probably appreciated peace as the basis of their business and thus gladly acquired a medal that depicted their view on the matter.

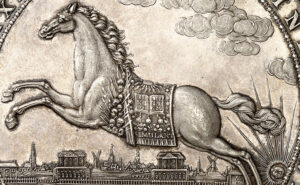

In order to comment on the death of William II on a medal, Dadler drew on well-known myths from ancient times. Thus, the obverse alludes to the Trojan horse, which carried ruin to Ilion in its belly.

On the obverse we see a large horse in front of the city view of Amsterdam. The horse is decorated with a magnificent saddle blanket. It features a sealed treaty with the inscription UNIO (= union) and RELIGIO (= denomination / faith). The saddle blanket represents the official propaganda of William II. He invoked his office as Governor General of the United Provinces of the Netherlands and propagated Calvinism as the religion that had to be protected everywhere.

What Dadler and his clients thought of this is expressed by the word SIMULANT, which is Latin for “they deceive, pretend”. This statement is illustrated by the soldiers hidden under the saddle blanket.

The legend comments the scene with a line from Virgil: From the one crime recognize them all as culprits. This refers to the arrest of hostile Amsterdam politicians by William II and his attack on Amsterdam – both happened on 30 July 1650, the date mentioned in the inscription. In other words, one should not pay attention to the propaganda of William II but to his deeds.

Detail of Sebastian Dadler’s medal commemorating the death of William II.The inscription in the exergue – he only did reject the war – is also from the Aeneid and compares the “crime” of the city of Amsterdam to that of Palamedes, who tried to convince the Greeks to call off the Trojan War. His desire to make peace was punished with death.

The reverse depicts the procession held on the occasion of the funeral service for William II. Courtiers with long coats and hats accompany the catafalque of the deceased Stadtholder pulled by eight horses in front of the scenery of The Hague.

But this funeral procession is virtually pushed aside by Dadler’s comment on the event. Again, it comes from Greek mythology: Dadler associated the young William II with Phaeton, who asked his father to let him steer the chariot of the sun. Apollon granted him his wish, but the boisterous driver was not up to the task. He got too close to the earth and started a great fire. In order to save the world, Zeus had no choice but to kill Phaeton by his lightning (or smallpox).

“He failed daring greatly”, reads the inscription on the reverse. It quotes a line of the epigram that is said to have been on Phaeton’s tomb. The date associated with it – 6 November 1650 – was the day William II died.

Sebastian Dadler signed this work twice.

PR Experts

Anyone who consults the relevant encyclopedias today will find that the young William II still enjoys the reputation of having been an inexperienced hothead who wanted to continue the Eighty Years’ War for selfish motives. We used these encyclopedias for the historical introduction.

The problem with this is that we are doing nothing less than adopting the excellent propaganda of the citizens of Amsterdam, who spread their view of things effectively by means of prints, copper engravings, paintings and medals. Sebastian Dadler also continued the myth of the peaceful and freedom-loving Dutch citizens with his medal. While doing so, he shows off his artistic talent in such a way that we are inclined to adopt the opinion of Amsterdam for the mere beauty of this piece.

However, present day teaches us that no party can always be right, and none can always be wrong – and that might have been the case in the 17th century too. William II simply didn’t grow old enough to propagate his position with a lasting effect.

This medal is on sale in Künker’s anniversary auction sale 350 from 29 June to 1 July 2021. You can find all coins of this auction online.

In this time the medals of Sebastian Dadler were very popular, learn more about a medal with the cityscape of Hamburg or a medal on the funeral of the Swedish King Gustavus II Adolphus at Riddarholm Church.

Read more about William I of Orange and the Dutch war of independence.