He was an enlightened Landgrave and of influence far beyond his realm: Louis VIII of Hesse-Darmstadt was born on 5 April 1691, as the eldest son of Landgrave Ernest Louis. He pursued his career at the service of the House of Habsburg as one of their closest confidantes and collaborators.

A Successful Commander and Enlightened Ruler

When he was still a crown prince, at the age of 31, Louis VIII entered the imperial military in 1722. This would be the beginning of a long-year, loyal collaboration with the House of Habsburg. In 1735, Emperor Charles VI named him commander of his cavalry. In this position, Louis VIII defended Maria Theresa’s rights in the First Silesian War and the War of the Austrian Succession.

The Austrian ruling couple appreciated Louis. In 1745, Francis I of Lorraine, Maria Theresa’s husband, accorded him the right to present to him the emperor’s election decree. The medal offered at Künker’s on 9 October 2019, showing the officer on horseback in commander’s pose, was likely made to commemorate this honor.

Louis VIII occupied the highest commanding posts in the Empress’ and the Empire’s army. During the Seven Years’ War, he served at the rank of General Field Marshal as Commander-in-Chief of the imperial forces – which made him the direct opponent of Frederick II of Prussia.

A great career, you see. And Louis VIII also achieved a lot for his own reign. He added the County of Hanau-Lichtenberg to his territory, as well as large parts of the Babenhausen district. He had numerous social institutions built and was considered sponsor of the arts – he was even active as a composer himself. How fitting then that he died in his box seat during an opera on 17 October 1768.

Nevertheless, whenever you read something about this ruler, the focus is on his love of hunting, as if that had been his only hobby …

Why Hunting Played Such an Important Role in the Baroque Period

Then again, Louis VIII was certainly not the only baroque ruler who went hunting. To the contrary: In his circles, hunting was every prince’s typical pastime, governed in all detail by the court protocol.

As early as the Middle Ages, hunting was divided into large game and small game hunting – the former being reserved for the nobles. It focused on red deer, fallow deer and wild boars, dangerous animals like bears, wolfs and lynxes, but also feathered game which was hunted with the help of falcons. While the common people may have caught their quarry with traps, the noble gentlemen were convinced it was solely their bravery and skill that allowed them to take down wild game.

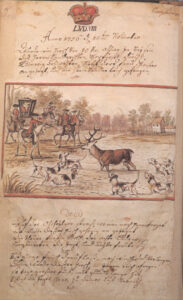

Although, they actually did have some sympathy for their noble opponent, at least in theory: On 11 November 1763, when a 32-point deer appeared during a par force hunt, it wasn’t shot but captured and presented in the Landgrave’s menagerie near Kranichstein. This event is commemorated by a medal that was auctioned off at Künker’s.

On the obverse, it shows a par force hunt held near Dianaburg, a hunting lodge built by Louis VIII. The principle of a par force hunt was the fact that, even though deer can run faster than hounds, the latter have greater stamina – thus, the hunting party had to follow on horseback along a completely unforeseeable route.

In the front, we see the stag and the hounds. Their position is being signaled by the two horsemen following directly behind, with their par force horns clearly visible in the image. These instruments, created solely for that purpose, could be carried over the shoulder thanks to their large windings, leaving the hands free during riding. Between the horn players is a piqueur, easily recognizable by his whip. His task was to drive forward the hounds. There is a fourth horseman coming out of the forest, turning around his horse.

Could this be the Landgrave? As the highest-ranking member of the hunting party, it was his right to kill the stag or, as in this case of the Battenberg Stag, to spare it.

The Costs of a Par Force Hunt

Par force hunting was expensive. When Louis VIII’s father, Ernest Louis, brought it to Hesse from France in 1708, he had to invest around 10,000 guldens. A simple livery for a hunting assistant already costed 579 reichstalers! Ernest Louis was the first to build an enclosure specifically for par force hunting. Because of the high costs, only ten German princes later copied him.

Louis VIII seems not to have done any par force hunting during his military career. We have a medal only from the year 1751 whose circumscription reads that this kind of hunting came “back from the dead” at that point in time.

How much Louis spent on this pleasure of his is witnessed by a precise testimony from 1760: 12,461 guldens. Of that amount, the chief huntsman received 300 guldens per year, the three piqueurs responsible for driving the pack of hounds got a total of 460 guldens, the hay for the 18 horses ridden by the hunting party came in at 923 guldens, the straw stood at 126 guldens. Feeding the pack of hounds alone cost Louis VIII 1,705 guldens.

19th-century literature tells about the huntsmen being very well paid, and receiving a little extra on top when the prince shot a deer. The one who had tracked down that deer received a “Hirsch-Dukaten” [deer ducat], tracking down a wild sow brought a “Sau-Dukaten” [sow ducat].

The Erotic Aspect of the Par Force Hunt

We do not know the purpose of this half taler offered at Künker’s. It is entirely possible that such souvenirs were given out to all participants of a hunt. That would fit the inscription “O wir armen Hörnerträger haben wider willen Schwäger“ [an untranslatable, ironical allusion to capons, used figuratively for men whose wives sought sexual satisfaction elsewhere, drawing also on similarities in deer with cut antlers that aren’t shed anymore]. Due to the unpredictable route the deer took to try to escape, the often over 100 participants of a hunting party were dispersed over a large area, providing time and place for a rendezvous which, in that erotic era, was practically part of the court protocol.

The medals and talers that were offered at Künker’s Auction 327 commemorate this era – and a ruler who is in fact wronged when slightly derogatorily called simply the Hunting Landgrave.

If you want to know more about baroque princes and their passion for hunting, continue reading here.

On the Künker website you can find the results of sale 327.