by Hertha Schwarz

Among the most beautiful and expertly-crafted medals celebrating the end of the second Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1683, one would most certainly name the creation of Nuremberg goldsmith and medalist Johann (Hans) Jacob Wolrab: a medal of 64.7 mm in diameter, designed in silver and in bronze, which shows, on one side, the highest-ranking princes of the relief battle fought at Kahlenberg Mountain on 12 September, and on the other side, the battle itself.

Gorny & Mosch, Auction 213 (2013), No. 4088; Dm 64.7 mm, 85.02 g, silver.

Kara Mustafa, Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed IV, had been occupying Vienna with around 170,000 men since 14 July, 1683. Yet, with only 15,000 men and employing all civilian forces, the imperial military commander Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg succeeded in defending the city until the arrival of the German-Polish relief troops. Finally, on 12 September, the relief forces reached Vienna.

A truly international confederation against the Ottomans

They consisted of imperial forces under imperial Lieutenant-General Charles V, Duke of Lorraine; troops of John George III, Prince-Elector of Saxony; Bavarian Prince-Elector Maximilian II Emanuel’s forces; imperial troops of Franconia and Swabia under Field Marshal Prince of Waldeck; as well as the by numbers largest contingency of John (Jan) III Sobieski, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, who had the overall command over the entire army. Jan Sobieski was able to lead about 65-83,000 men with approximately 150-179 cannons.

The alliance was supported by Pope Innocent XI and the Republic of Venice, which was fighting the Turks on the Peloponnese. If there ever was a European endeavor across ethnic and denominational boundaries worthy of that name, it is the relief of Vienna in 1683: The soldiers and officers of the army came from all over the German Empire (Holy Roman Empire), because the Emperor could recruit soldiers anywhere except in the electoral territories. In addition, there were the soldiers from the Habsburg Hereditary Lands, which were not part of the Empire, as well as supporting troops from Venice and Spain. The Polish army in turn, besides Polish and Lithuanian soldiers, even featured Cossacks. Innumerable noblemen from all over Europe made themselves available for the Emperor; a significant number of Frenchmen defied the prohibition made by their King Louis XIV – who had the nickname “most Christian Turk” in the German Empire – and joined the imperial forces.

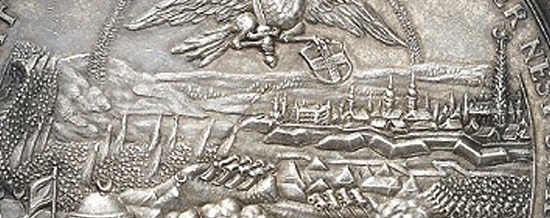

Details of the reverse with view of the city of Vienna and its immediate surroundings: in the back on the right Vienna with St. Stephen’s Cathedral and the Leopoldstadt district, on the left Kahlenberg Mountain.

Vienna in detail

On the side that has traditionally been identified as the reverse, Hans Jacob Wolrab’s medal shows fortified and besieged Vienna, up to the location of St. Stephen’s Cathedral; far in the background lie the Leopoldstadt district and the land east of the Danube. The characteristically high tower of the Cathedral still carries the old weather vane, the so-called moonlight – a crescent with a star –, that had to be removed after the end of the siege, since it was now equated with the Turkish crescent, which, after 1683, people associated with nothing but death and endless suffering.

Opposite the besieged city, on the left edge of the image and geographically north of Vienna near Nussdorf, Kahlenberg Mountain rises up.

An endless procession of foot soldiers with waving regiment flags comes pouring down the mountainsides, charging towards the two batteries, each consisting of four cannons, in the center of the image. The Ottoman chronicler of the Siege of Vienna describes that, on Sunday, 12 September, “the giaours (the infidels, i.e. Christians; author’s note) … (appeared) on the slopes with their units like storm clouds, rigid with dark-blue ore. One flank touching on the Danube bank opposite the Vlachs and the Moldovans, the other flank reaching all the way to the outermost units of the Tatars, they covered mountain and fields and formed up in crescent-shaped battle array. It was as if a flood of black pitch came rolling down the mountain, crushing and burning everything in its way. That is how they attacked, with the vain intention of encircling the fighters of Islam from both sides.”

Detail of the medal showing imperial and Bavarian troops charging the main Turkish position before Vienna.

Looking closely: The army in action

In the foreground, in front of this “pitch flood” of the infantry, saber-swinging cavalrymen jump onto the scene; a large, crescent-bearing tent has already been run over by them, and through a cloud of dust they go after the enemy who is fleeing on horseback as well as on foot, across the bodies of the fallen lying on the ground.

According to the positioning of the imperial troops as described in the reports, the Saxonians under the command of their Elector John George III can be seen on the left in the back of the picture, right at the foot of the mountain, being the first to push back the Turks. The Bavarian troops led by their Elector Max Emanuel, together with the other German forces, made up the center of the front. Even though, initially, they could only make slow progress due to the impassable terrain, they were the first to reach the main Turkish position.

In the medal’s image, this is probably depicted by the camp of tents which is secured on both sides by a battery of four cannons each. Finally, the horsemen in the very foreground of the medal would be the cavalry led by Jan Sobieski, going directly for the Ottomans’ holy flag and essentially contributing to the victory with their powerful attack.

Independent confirmation from Turkish sources

It is absolutely impossible that Hans Jacob Wolrab had seen the Turkish report of the Master of Ceremonies, and still, his medal “reads” like a literal depiction of the latter’s words: “Then, the giaours started an assault and pushed our men out of their positions; subsequently, our men counterattacked and drove the giaours back up the hills. Eventually, the giaours, infantry with chevaux de frise (portable barriers/entanglements; author’s note) first and cavalry behind, charged our men like mad hogs, driving them downhill into the destroyed village (Nussdorf; author’s note). There, the battle went back and forth for a while, before the scoundrels, charging in closely-packed masses, were able to break through our lines on the left and on the right, now attacking the fighters of Islam from all sides. They carried their Sahi cannons (light field cannons; author’s note) on limbers and used them to cover the army of Islam with a storm of missiles. On the Danube bank, they hit the troops under the command of Vizier Koca Arnaud Ibrahim Pasha and made their way into the valley and towards our great army camp. … When the troops under the Grand Vizier saw the enemy charging towards them from both sides, and the army of Islam began to get ready to flee, each one of them lost their strength and will to struggle and strive and the sort of confusion arose that is always followed by defeat. … But the attacks by the giaours became stronger and stronger, the battle got more and more intense, lasting five or six hours already. The army of Islam was covered with missiles from the enemies’ cannons and guns as with rain. Thus, the Muslims realized that all was lost and the catastrophe could no longer be avoided. Fighting and fencing, the masses of warriors around the Grand Vizier turned to flee; most of them fled directly to their tents, wishing only to save their lives and belongings.”

A rainbow spans the fighting, below it sits an eagle with a sword and the coat of arms of Vienna.

Victory with God’s help

Spanning the entire scene from Kahlenberg Mountain to the land east of the Danube is a rainbow, a dove with an olive branch in its beak perched on the crown. It is not the dove of peace that would become known later, but the dove of Noah, bearing the good news of the end of the Flood with this green branch. Below the rainbow, which in Christian symbolism stands for the presence of God, and filling out its width with its wings, sits the single-headed, crowned eagle, carrying a sword and the coat of arms of Vienna in its claws. The entire image is framed by a ribbon bearing the inscription WIEN DAS ADLER NEST SICH FREUET, DAS DER TÜRKEN HEER ZERSTREUET. DANCKE GOTT O CHRISTENHEIT [Vienna, nest of the eagle, rejoices that the Turks’ forces were dispersed. Thank God, oh Christianity]. The artist’s initials – HIW – can be found on a rock in the very foreground of the scene.

The obverse depicts the four highest-ranking princes that took part in the battle. In prayer, they are giving thanks for their victory.

The Christian princes give thanks for the victory

The obverse shows the four highest-ranking princes who fought in this battle, united in thankful prayer.

The scene is not a prayer before the battle, but the act of giving thanks for the victory, which can be recognized by the Sultan lying in the dust (if it is not supposed to be the Prophet himself).

The fact that they are already thanking God for His assistance and not only asking for His help is shown by the name MAHUMED – whether it stands for the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed IV or even the Prophet himself – in the dust, with distorted letters under sword and saber by the princes’ feet, while they have turned their eyes upwards to the name of Jesus, crowned with rays.

The princes in detail, from left to right: Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria; Maximilian II Emanuel, Prince-Elector and Duke of Bavaria; John George III, Prince-Elector of Saxony; and John (Jan) III Sobieski, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania.

In full vestment, from left to right, identified by their respective coats of arms in addition to the easy-to-recognize physical appearances, are kneeling down: Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria; Maximilian II Emanuel, Prince-Elector and Duke of Bavaria; John George III, Prince-Elector of Saxony; and John (Jan) III Sobieski, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania.

Leopold and Jan Sobieski are wearing crowns, the two Prince-Electors the electoral hat. Leopold and Max Emanuel, as a sign of devotion, have put their palms together, whereas John George is praying with his fingers interlocked, which at the time identified him as a Protestant.

While Leopold, Max Emanuel and John George have raised their hands in prayer, Jan Sobieski, the only one of the pictured princes without the full-bottomed wig and suit of armor underneath the vestment, has placed his right hand on his heart, while pointing with his left hand to the edge of the image. This is the typical offering gesture, drawing God’s attention to the offering made, in this case the defense of Christianity through the victorious battle at Kahlenberg Mountain, pictured on the reverse.

This image, too, is framed by a circumscription: WANN DIESE HELDEN SIEGEN SO MUS DER TÜRK ERLIEGEN, HUNGARN DER FRIED VERGNÜGEN [Where these heroes win, the Turk must lose, Hungary rejoice in peace], complemented by the year 1683, split in two. The medal’s raised edge-lettering – Hans Wolrab is said to have been the first in the German Empire to use milling technique for creating raised edge-lettering – specifically calls on Vienna to be thankful: WIENN BEDENCKE GOTTES GNAD * SO ER DIR ERWIESEN HAT * DANCKE IHM ALLZEIT FRÜE U(ND) SPATH [Vienna, remember the grace of God * That He has proven to you * Thank Him at all times].

A visionary medal image

The image Hans Jacob Wolrab created on his medal could, in hindsight, almost be called clairvoyant: The fleeing movement of the Turks out of the picture symbolically anticipates the gradual displacement of the Ottomans, beginning in 1683, out of Hungary and eventually all of Europe.

During the counterattack that already started in 1683, Buda was captured in 1686; a large Ottoman army was defeated near Mohács in 1687; Belgrade was conquered in 1688; in 1689, the imperial forces under Louis William, Margrave of Baden-Baden, who had already been part of the relief of Vienna, advanced all the way to Nis and Vidin; finally, in 1691, the Türkenlouis (“Turkish Louis”), as the Margrave of Baden-Baden was called, defeated the Turks so badly at Slankamen that the Turkish danger in the east was averted for a couple of years.

In 1697, Eugene of Savoy-Carignan, who would go down in history as Prince Eugene, eventually destroyed almost an entire Ottoman army before the eyes of the Sultan Mustafa II, at Zenta near the river Tisza. In 1699, the Treaty of Karlowitz, in which the Ottomans had to accept the conditions dictated by a Christian power, put an end to the Great Turkish War that had started in 1683 with the Siege of Vienna.

Hungary was reestablished and, with the exception of the Banat in the south-east, freed from Ottoman rule, and it was stronger under Habsburg influence than ever, since, after the Battle of Mohács in 1687, the Hungarian Diet had recognized the heritability of the Hungarian crown within the House of Habsburg. This is where the shaping of the Austrian imperial-royal monarchy starts that would be an essential influence on the fate of Europe for the following 200 years.

Literature:

R. Kreutel (editor), Kara Mustafa vor Wien. Das türkische Tagebuch der Belagerung Wiens 1683, verfaßt vom Zeremonienmeister der Hohen Pforte. Translation, preface and annotations by R. F. Kreutel (Graz 1955), esp. p. 106-111.

G. Gerhartl, Belagerung und Entsatz von Wien 1683 (Militärhistorische Schriftenreihe, issue no. 46, Neudorf 1982).

K.-P. Matschke, Das Kreuz und der Halbmond. Die Geschichte der Türkenkriege (Düsseldorf 2004).

In our current CoinsWeekly Special Edition on the Numismata in Munich you can read an extensive article about the medals on the victories of Maximilian II Emanuel of Bavaria in the Great Turkish War 1683-1699 (only available in German).