by Univ-H.Prof. Doz. DDr. Helmut Rizzolli, President of the Stiftung Bozner Schlösser

translated by Teresa Teklic

The coin history of the historial Tyrol region begins with the circulation of coins from Celtic tribes. Tyrol as a region was an important part of the Celtic world as Celtic tribes would constantly cross it on their way to other destinations. Between the 5th – 1st century BC Celtic tribes migrated to Eastern France, Western and Southern Germany, the British Isles, Southern France, Spain, Northern Italy, Bohemia, Noricum and as far as the Black Sea. Wherever they went, they sold their military skill to foreign armies. You could say they were the “mercenaries of Antiquity”. The money that Celtic mercenaries returning from the Mediterranean carried with them when moving north probably started the use of coins in the Alpine region and Southern Germany.

In the Alpine valley Etschtal, two major Celtic currency zones collided: Northern Italian restrikes of the silver drachms from Massilia (today: Marseille) and the so called Bavarian rainbow cups, ca. 7.5 g heavy gold staters.

Although the rainbow cups discovered in Brentonico in 1827 were lost, the myth that they were created by rainbows survived. Source: Bürgerblog Brentonico.

According to popular belief, rainbows left a piece of gold – the rainbow cups – behind where they had touched the ground. Gold coins like this very often surfaced on fields after heavy rainfalls.

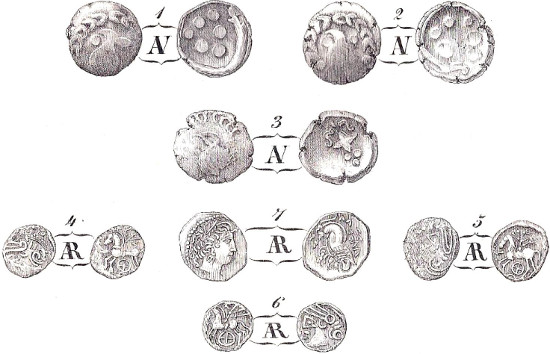

In 1871, Gian Battista Noriller made drawings of some of the coins found in Brentonico. Numbers 1-3 refer to Southern Italian Celtic rainbow cups, 4-6 to Gaulish coins from the Lingones, number 7 depicts a Celtic Massilia-restrike from the Po Delta.

Similar circumstances also led to the discovery of three Celtic rainbow cups in Castello, near Brentonico (Rovereto), back in the year 1827. The coins were found together with several other Celtic Massilia-restrikes and another six silver coins of the Aedui or Lingones (Kaletedu-type). The coins were acquired by Giovanni Battista Noriller (1789-1872), an attorney, who described and illustrated them in his book “I Lavini di Marco” (Rovereto, 1871). In 1834, another thousand Celtic drachms of the Massilia type were discovered, three of them with the inscription P I R A K O S. In 1854, 250 Padanian drachms were found on the same excavation ground.

Museum pays his heating bills with Celtic gold coins

In 1923, the Noriller collection and the Brentonico coins ended up in the collection of famous archaeologist Paolo Orsi and were then exhibited in the Museum in Rovereto. 15 years ago, two of the Brentonico rainbow cups suddenly appeared on the Veronese coin market.

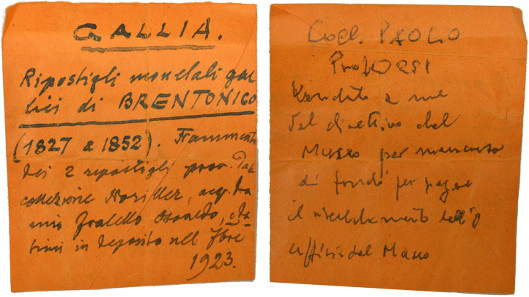

This document tells us that the coins were given up for sale by the Museum in Rovereto in order to pay for heating bills. The document was found among the Celtic gold coins at an auction a few months ago.(Coll. Paolo Prof. Orsi. Venduto a me dal direttivo del museo per mancanza di fondi per pagare il riscaldamento dell’ufficio del museo).

It is only from this old document found with the third gold coin, which was auctioned in Munich a few months ago, that we know why the museum in Rovereto, which possesses large parts of the Paolo-Orsi inheritance, does not have the Brentonico gold coins anymore. The museum sold the coins in the 1920s in order to pay for the heating costs of the museum’s office rooms. Turns out, even museums cannot guarantee safe storage anymore, at least not in times of need!

Now all three rainbow cups have unexpectedly reappeared. After they were lost for almost 100 years, it is fortunate that they are available again for scientific examinations such as weight and metal analyses.

Imagery of the Celtic rainbow cups: the eagle

Unlike other Celtic gold coins, whose origin can with certainty be traced to Greek coins, the imagery on the rainbow cups from Southern Germany established a completely autonomous symbolic language. That is why scholars in the 17th century believed the coins had literally fallen from the sky or sprung from the earth.

This unfamiliar, abstract and often purely ornamental imagery was often considered primitive and barbaric up until the 19th century. Today, in a time where we are used to the style of artists like Klee, Picasso or Mirò, we can appreciate the imaginative design of some Celtic coins.

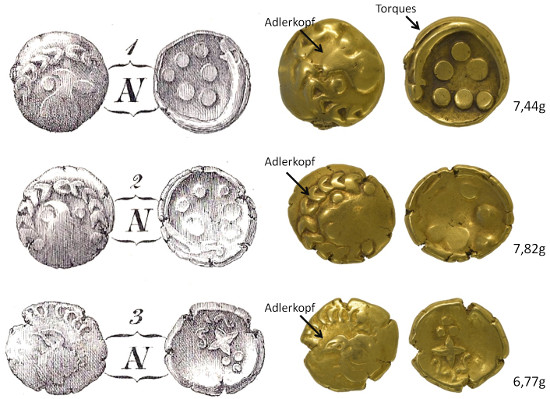

Comparison of Norill’s drawings and the rediscovered originals.

All three gold coins from Brentonico, which with regard to their weight (6.77 g to 7.82 g) nominally correspond roughly to Greek staters, depict a convex bird head with a curved beak. Two of them further show a torc and six balls inside it on the concave side. These coins also feature a ball above and below the beak. The balls possibly indicate the coin’s value in analogy to the Republican Roman As, a bronze coin with a ship bow.

The famous ‘Dying Gaul’, exhibited in the Capitoline Museum in Rome, wearing a torc.

The depicted torc is a metal ring which was worn by Celtic, or more precisely by Gaulish, warriors as necklace and status symbol, like the famous “dying Gault” in the Capitoline Museum does. However, some experts interpreted the ring as the rainbow creating the rainbow cups.

The third gold stater from the Brentonico find does not only show the usual eagle head, but on the concave side, also a four pointed star with three balls above and two volute urns filled with corn below.

The rainbow cups date back not later than mid 1st century BC. This dating relies partly on the average weight of 7.5 g and the reduced gold content of 69-70 per cent, which still needs to be confirmed. They are most often attribtuted to the Vindelici, the Celtic neighbours of the Raeti, and because of the moulds found in the Celtic city of Manching (near Ingolstadt) it is assumed that they were minted there.

Who hid the unique Celtic coin treasure in the first place?

Although there have been single finds of rainbow cups in the historical Tyrol region (Himmelreich near Wattens, Siebeneich/ Greifensteiner Hand, Sigmundskron, Berg Isel/ Innsbruck), the extensive collection of Celtic gold in Brentonico is unique. Certainly, the find belongs to the transalpine Iron Age culture of the municipality Fritzens, but the collision of Southern German, Padanian and Gaulish (Lingones) Celtic coins still requires some explanation.

In 1998, Christina Bassi suggested that the find spot, which is exposed and facing the Etschtal, had been a place of pilgrimage; weapons she found in the spot and which had been rendered useless supported her theory. In the same year, she was strongly contradicted by Giovanni Gorini who draw entirely different conclusions. Gorini believes the only plausible explanation for the Brentonico coins is as booty of Roman veterans from Caesar’s campaign against the Vindelici 59/58 and 57/56 BC, when the military leader wintered in Aquileja with his three legions.

Another connection which comes to mind is that between the Brentonico finds, which still have to be dated more precisely, and the coins finds at the Wattener Himmelreich. The Wattener Himmelreich is a Raetian settlement and the coins, including the rainbow cup, were found on a dome which used to have a fireplace for burnt offerings on it.

You can find more articles about Celtic Coins in our Archive under “Ancient Coinage/ Celts”.