by Sebastian Steinbach

King Louis’ I “historic thaler” made impression in Russia and left it’s marks. Tsar Nicholas I struck similar coins with his family on the reverse. How this happened and why there are five different types you can read here.

In September 1835, Russian Ambassador Prince Grigory Ivanovich Gagarin sent a coin from Munich to the Russian Minister of Finance, Count Yegor Frantsevich Kankrin, to complete the coin collection in the St. Petersburg Hermitage. The coin the ambassador was so thrilled about had been issued by Bavarian King Louis I (1825-1848) in 1828.

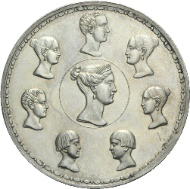

Bavarian model: historical thaler “Segen des Himmels” (‘blessings of heaven’) minted by King Louis I (1825-1848). AKS 121; Dav. 563, Kahnt 83; Thun 56. Künker 169-173 (Osnabrück 2010), no. 3605.

It was one of the “historical thaler” of the king with the ruler’s portrait on the obverse and a depiction of his family (his wife and his eight children) on the reverse – called by the inscription “Segen des Himmels” (‘blessings of heaven’). Since the 10th anniversary of the Tsar’s rise to power was approaching, Count Kankrin decided to commission a similar coin. With this “family rouble” one of the most coveted rarities of the history of Russian coinage came into being, which, by the way, was the only contemporary coinage that showed the facial features of the ruler …

A Russian-German coin story

Although he wasn’t destined for the succession to the throne at first, Nicholas I had shaped an entire era of Russian history and given it his name. During his age the sciences flourished, it was a time of Tsaristic splendor but also a time of war and sometimes imposed domestic stability. A major part of the profound changes in the Russian Empire in the first half of the 19th century rooted in the nature of the Tsar and his childhood.

Nicholas was born on June 25, 1796 in Zarskoje Selo near St. Petersburg as third son of Grand Duke Paul Petrovich and his second wife Maria Fedorovna. Only 5 months later his father ascended to the throne as Tsar Paul I (1796-1801). In contrast to this two elder brothers Alexander and Constantine who had been raised mainly by their grandmother, Tsarina Catherine II “the Great”, young Nicholas was shaped by his father’s passion for the army.

Nicholas already wore a uniform when he was only three years of age and rather lived in the army than study foreign languages and complex sciences. He found a kindred spirit in Prussian Princess Friederike Luise Charlotte Wilhelmine, daughter of King Frederick William III (1797-1840), who shared his fondness for the military. Frederike’s childhood had been influenced by the impressions of the Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815). When her mother, famous “Queen of the Hearts” Luise (1776-1810) died unexpectedly, Charlotte, only 12 years of age, became first lady at the court and had to fill the representative gap.

After the engagement of Napoleon on the island of Elba in April 1814 and in preparation of the Congress of Vienna, Grand Duke Nicholas, together with his brother Michael, resided in Berlin where he became acquainted to the young princess. It is said that already during their first visit negotiations had been conducted about a marriage between Charlotte and Nicholas.

In June 1817, two years after her engagement with Nicholas, Charlotte, accompanied by her brother William (later to be Emperor William I, 1861-1888), traveled to St. Petersburg where she converted to the Russian-Orthodox faith and assumed the name Aleksandra Fedorovna. On her 19th birthday, on July 13, 1817, she got married to Grand Duke Nicholas Pavlovich and hence became Grand Duchess. The young couple preferred the privacy and conducted a life pretty much secluded from society and politics on Peterhof Palace at the Gulf of Finland – approximately 30 km distant from St. Petersburg.

Russia. Alexander I, 1801-1825. Silver medal 1825, from A. Klepikov, on his death. Bust r. with laurel wreath, surrounding ouroboros // radiant all-seeing eye. 68.13 mm; 116.19 g. Diakov 429.2 (R2). Künker 174-179 (Osnabrück 2010), no. 8361.

The reluctant Tsar

On November 19, 1825, Nicholas’ brother, the great Tsar and victor over Napoleon, Alexander I (1801-1825) died unexpectedly during a recreational holiday in Taganrog near the Sea of Azov (fig. 2). No official arrangements had been made as to his succession. His wife dying shortly after him without leaving any heir, Constantine, his second younger brother, ought to have ascended the throne. Constantine, however, had entered a marriage with the Polish Princess Joanna Grudzinska, which wasn’t befitting his social standing, and had abdicated the throne already in a small circle of family and friends, so that Alexander I had invested his brother Nicholas with the succession in a secrete manifesto in 1823. Despite his mother’s intervention, Nicholas accepted the undesired succession only when Constantine renounced the throne officially.

Russia. Key of the Chamberlain designed during the reign of Nicholas I. Künker 188-192 (2011), no. 8782.

Being afraid of the omnipresent nightmare of an imminent revolution, the ‘reluctant Tsar’ was willing to correct the defeats in the country – but only with patronizingly reforms. He therefore had the 15 volume “Collection of Laws of the Russian Empire” (Svod Zakonov) prepared without compromising the privileges of the nobility. Against the wish of his Minister of Finance Kankrin he pushed the expansion of the Russian railway through and inaugurated in 1851 the connection between Moscow and St. Petersburg, later to be called “Nicholas Railway”. The Tsar’s thoughts weren’t all towards economy. He rather wanted a chance to deploy his troops to their places of action much quicker in the future.

Russia. Nicholas I, 1825-1855. Silver medal 1835, from A. L. Held, on the troop inspection near Kalisch. 33.81 mm; 14.13 g. Diakov 524.2 (R1); Marienb. 3832. Künker 169-173 (Osnabrück 2010), no. 7402.

The army with its display of splendor generally played a decisive role during the reign of Nicholas I. That became particularly apparent in the Prussian-Russian troop inspection of Kalish, which was depicted in numerous contemporary paintings and on medals, too. More than 60,000 soldiers with 136 cannons and 7,000 horses participated in this exercise from September 12 to 22, 1835. The Prussian troops were commanded by Crown Prince William, the Russian ones by the Tsar himself. The maneuver was concluded by a huge military concert with more than 2,000 musicians and impressive fireworks, which allegedly cost more than 100,000 thaler. In the same year the first test strike of the family rouble was produced.

A rarity in the history of coinage – the family rouble

As early as ancient times, famous rulers had themselves depicted in impressive images on coins and medals. Wealthy Tsar Nicholas I wasn’t satisfied with that: he wanted to see not only himself but likewise his family minted in metal forever. As already mentioned, the present of the Bavarian historical thaler “Segen des Himmels“ (‘blessings of heaven’) by the Russian ambassador to Minister of Finance Kankrin initiated that. The latter commissioned the young but very skilled die cutter Pavel Petrovich Utkin with the production of the dies, who was working as a medalist at St. Petersburg Mint only since 1835.

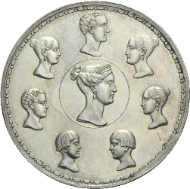

In the strict numismatic sense, the term “family rouble” isn’t quite correct because the minted nominal value rather is 1 1/2 rouble or 10 zloty. Circulation coins of the same Russian-Polish denomination were manufactured under Nicholas I in the Mints of St. Petersburg and Warsaw already since 1833 and 1835, respectively. In regard to the portraits of the children of the Tsar, Kankrin suggested copying them from the tobacco tin of Count Golicyn. Depicted are the following ones (clockwise, beginning at 12 o’clock):

- Alexander (II), April 17 – March 1, 1881 (Tsar 1855-1881).

- Maria, August 6, 1819 – February 9, 1876 (married to Maximilian Josèphe Eugène Auguste Napoléon de Beauharnais, Duke von Leuchtenberg 1817-1852).

- Olga, August 30, 1822 – October 18, 1892 (married to King Charles I Frederick Alexander of Wuerttemberg 1823-1891).

- Constantine, September 9, 1827 – January 13, 1892 (Grand Duke of Russia).

- Nikolas, July 27, 1831 – April 13, 1891 (Grand Duke of Russia).

- Michael, October 13, 1832 – December 5, 1909 (Grand Duke of Russia).

- Alexandra, June 12, 1825 – July 29, 1844 (married to Landgrave Frederick William (II) George Adolph of Hesse-Kassel-Rumpenheim 1820-1884).

At the beginning of December 1835, Utkin presented the first draft (type 1), which, in contrast to its Bavarian model, had a very short inscription. The coin showed neither the title of the monarch nor a statement referring to the occasion of its being issued (the 10th anniversary of the beginning of his rise to power). Instead, only the year, 1835, and the nominal value (1 1/2 rublja. – 10 zloty (Cyrillic)) as well as the full name of the die cutter (R. P. Utkina (Cyrillic))were stated on the coin’s obverse and reverse. The signature on the reverse, in addition, wasn’t entirely correct since the family name lacked the grammatically required hard sign “A“.

46 specimens were minted of this first pair of dies of which 36 were given to the Minister of Finance to be presented to the Tsar. On December 6, 1835, Kankrin presented Nicholas I with the test strikes. The Tsar approved of the idea of a commemorative coin but required that some changes were made. First and foremost he was displeased with the depiction of his 36 year-old wife since she appeared older and, to his eyes, too similar to his mother in law.

Utkin thus made a second design according to the ruler’s wishes (type 2). This draft, dating to 1836, didn’t show any medallion-shaped circles around the heads on the reverse anymore, and the wrong signature was omitted. Most striking, however, were the changes being made in regard to the Tsarina’s portrait on the reverse: the double chin was removed, and the entire character appeared “younger”. Nicholas approved of the new draft and ordered on February 2, 1836, to harden the dies for the production and to manufacture 100 pieces. The first die of this coinage, however, burst after only 50 specimens so that a new one had to be made.

On the third pair of dies (type 3) the die cutter’s signature on the obverse was again abbreviated to the initials P. U. instead of R. P. in Cyrillic script and moved from the edge on the neck truncation of the monarch. According to the wishes of the Tsar, 150 specimens were produced with these dies in three stages between 1836 and 1837. Allegedly, a gold pattern of this type was likewise being made (Bitkin 890).

Even after this official emissions on the orders of the Tsar, the mint produced the family rouble from time to time as novodel by using the original dies, to be given away as present or to be collected (type 4). In the course of time, however, the edge of the reverse die chipped, the bigger the mintage the more. By commission of private persons further restrikes were produced until a part of the edge dropped away completely. This very part of the edge of the 4th section coins was roughly mended.

Because there was a continuous demand for restrikes of the family rouble and since the mint didn’t have suitable left in 1847, a fourth pair of dies was produced (type 5). A striking feature is that this design completely omits the signature of the die cutter. A possible reason for this is that Utkin suffered from an eye illness in the last years of his life and wasn’t able anymore to make the dies himself. They were produced by another medalist (probably one of his pupils) who, out of reverence for his master, omitted the latter’s signature.

In the same year, 1847, the mintage of restrikes from the St. Petersburg Mint was greatly diminished at the request of a number of influential Russian numismatists, which is why there are only some extremely rare patterns from the last pair of dies extant. The last family rouble of this fifth type was auctioned off 80 years ago in auction Hess 204 “Dubletten russischer Museen” (Frankfurt a. M. 1931), under lot no. 979. No entire set of all five family rouble variants has been sold at an auction so far.

In the end, no more than only very few test specimens of the family rouble were made. No comprehensive emission has been produced, thus these truly rare pieces are the only coinage of the Tsar, which, apart from medals, show his portrait. All other circulation coins only depict his monogram (a crowed “N” above the Roman number “I”) and / or the Russian eagle. Not least because of this they range amongst the coveted rarities of Russian numismatics.

Tsar in turbulent times

As to the reign of the Tsar, it can be sumed up that Nicholas ultimately wasn’t successful in his attempt to break the chains his era and his character imposed on him. Urgently needed top-to-bottom reforms weren’t concluded, despite the Tsar’s open-mindedness and the omnipresent fear of a revolution. In addition, after several successful military operations like the Russo-Persian War (1826-1828) or the Russo-Turkish War (1828-1829), which brought the Russian Empire big territories, he acted quite unlucky in the “Oriental Question”.

Russia. Order of St Stanislav, 2nd model (1831-1917), cross of the first class, second type (1841-1917). Künker 174-179 (Osnabrück 2010), no. 8764.

His attempts to take advantage of the weakness of the Ottoman Empire in order to gain access to the Mediterranean Sea and to expand his influence on the Balkans, led Nicholas I into the Crimean War (1853-1855). Being completely isolated in regards to foreign policy, Russia fought a losing battle when France, Great Britain, Sardinia, Piedmont and later even Austria – a former ally of Russia – intervened in the conflict in favor of the Turks. The Tsar didn’t live to witness the end of the Crimea War involving heavy losses. He died unexpectedly on February 18, 1855, and Alexander II (1855-1881), who is likewise depicted on the family rouble, followed in line.

Without doubt Nicholas had put his mark on this era and shaped our perception of splendor and power of the Russian Empire in the 19th century to a great extent. He, on his part, regretted not being able to hand over a “peaceful, well-arranged and happy empire” to his son but at the same time gave him an advice, that fits his character so well, in case the empire got into a state of disorder: “Mount the horse at once, show courage where is it required […] and you will safe Russia!”

On February 2, 2012, during of the Berlin auction of the Fritz Rudolf Künker all five variants of the family rouble will be offered for sale for the first time ever. Further details and the leaflet providing historical background information are available at +49 (0)541-96 20 222 or service@kuenker.de!

You will find this brochure online.

If you want to go directly to the sale, click here.

Little catalog of types of the family rouble of Tsar Nicholas I (1825-1855)

Type 1

1835

Av.: 1 1/2 rublja – 10 zloty (Cyrillic) 1835. Bust of the Tsar to the right.

Rev.: Medallion with the bust of his wife Aleksandra Fedorovna to the right with diadem, surrounded by the busts of her seven children in medallions.

Name of the die cutter R. P. Utkina (Cyrillic) on the obverse below the neck truncation and R. P. Utkin (Cyrillic) on the reverse below the medallions.

Bitkin 885 (R3); Davenport 286; Kaim K 257 – pattern; Uzdenikov 4134 (fig. 02); Severin 3114. Only 36 specimens were minted.

Type 2

1836

Av.: 1 1/2 rublja – 10 zloty (Cyrillic) 1836. Bust of the Tsar to the right.

Rev.: Medallion with the bust of his wife Aleksandra Fedorovna to the right with diadem, surrounded by the busts of her seven children in medallions.

Name of the die cutter R. P. Utkina (Cyrillic) on the obverse below the neck truncation.

Bitkin 886 (R3); Davenport 286 A; Kaim K 257, Var. 1; Uzdenikov 4137 (fig. 04); Severin 3180. Only 50 specimens were minted.

Type 3

1836 (minted in 1836/1837)

Av.: 1 1/2 rublja – 10 zloty (Cyrillic) 1836. Bust of the Tsar to the right.

Rev.: Medallion with the bust of his wife Aleksandra Fedorovna to the right with diadem, surrounded by the busts of her seven children in medallions.

Name of the die cutter abbreviated P. U. (Cyrillic) on the obverse below the neck truncation.

Bitkin 888 (R2); Davenport 286 B; Kaim K 257, Var. 2; Uzdenikov 4136 (fig. 03); Severin 3181. Only 150 specimens were minted.

Type 4

1836 (minted after 1837)

Av.: 1 1/2 rublja – 10 zloty (Cyrillic) 1836. Bust of the Tsar to the right.

Rev.: Medallion with the bust of his wife Aleksandra Fedorovna to the right with diadem, surrounded by the busts of her seven children.

Name of the die cutter abbreviated P. U. (Cyrillic) on the obverse below the neck truncation. Clearly visible die chips on the edge of the reverse.

Bitkin H889 (R1) – Novodel; Davenport to 286 B; Kaim K 257, to var. 2; Uzdenikov to 4136; Severin to 3181.

Type 5

1836 (minted in 1847)

Av.: 1 1/2 rublja – 10 zloty (Cyrillic) 1836. Bust of the Tsar to the right.

Rev.: Medallion with the bust of his wife Aleksandra Fedorovna to the right with diadem, surrounded by the busts of her seven children.

Without the signatur of the die cutter.

Bitkin H891 (R3) – Novodel; Davenport 286 C; Kaim K 257, var. 3; Uzdenikov 4138 (fig. 05); Severin 3182.

Bibliography

- Bitkin, V.: Composite Catalogue of Russian Coins, 2 vols., Kiev 2003.

- Diakov, M. E.: Medals of the Russian Empire 1672-1917. 7 vols., no place 2004-2007.

- Van Hoof, F. / Schoevaert, A.: Monnaies Russes 1700-1917. V. V. Uzdenikov, 2 vols., Moscow 1985 / RNS-USA 1988.

- Kaim, R.: Die Münzen des Zaren Nicolaus I. 1825-1855 (Russland-Serie-Spezial, vol. V), Hagen 1982.

- Kratzer, N.: Nikolaus I. 1825-1855, in: Torke, H.-J. [ed.]: Die russischen Zaren 1547-1917, Munich 2005, pp. 289-314.

- Lincoln, W. Bruce: Nicholas I., Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russians, London 1978.

- Schiemann, T.: Geschichte Russlands unter Kaiser Nikolaus I., 4 vols., Berlin 1904-1919.

- Severin, H. M.: The Silver Coinage of Imperial Russia 1682 to 1917, Basel / Amsterdam / London 1965.

- Spasski, I. G.: Das russische Münzsystem. Ein historisch-numismatischer Abriss, Berlin 1983.