translated by Christina Schlögl and Annika Backe

in memoriam Georg Baums

War was still dominated by comparatively small mercenary armies. The famous battle of Pavia, for instance, “only” saw about 25,000 men fighting on each side. During the Thirty Years’ War, the famous field commander Tilly was of the opinion that any battle formation with more than 30,000 people could not be commanded any more. In this episode, you will read how siege warfare lost its importance due to the deployment of bigger armies.

During the famous Escalade in Geneva in 1602, the Savoyards tried to sneak into the city with two ladders. Switzerland, 5 francs, commemorative coin of 2002. Photo: Swissmint.

Siege war since the regular use of firearms (1500-1650)

It should take many more years until a field commander could be certain, he would inflict serious damage at the opposing army. In our regarded period from 1500 until 1650, war mostly meant raiding small, unsecured parts of the enemy’s territory, occupying and plundering them. The numerous smaller cities were ideal prey, as plundering them promised more profit than raiding the villages. Practically every city of the Early Modern Age was fortified and therefore war automatically meant siege war.

There were several ways to storm a city. Certainly the best method was one that would minimise losses on the intruder’s side. Consequently the most popular option was strategy or ‘ruse de guerre’. Sturdy soldiers would disguise themselves as citizens of the town, traders on their way to the market for instance, or even women. They would hide in carriage loads or between animals in a herd that was granted access to the town.

Frederick IV of Denmark. Medal 1700 on the besiegement of Tönning. Both sides clearly show that bombards were used, which could shoot behind the city walls. From Baums Collection, Künker sale 116 (2006), No. 4636.

If strategy did not suffice any longer, the only option left was violence. If one had a suspicion that the fortress had too many people with too little food in it, one could simply cut the city off the enemy’s supplies and start a formal occupation that lead to surrender of the starving people of the city. Certainly one could also just storm a city. But this was rarely successful. Thus most field commanders counted on a combined method: They locked the city, tried to stop supplies and started to tire the garrison out and discourage the population with small attacks. Constant fire would do the rest and clear the way.

The attackers knew two fundamentally different kinds of bombardment. Firing directly at the city walls with canons and firing past the walls into the city using a bombard. They used it to cast tape records and other things deep into the city. They hoped to cause as much damage as possible with their uncoordinated shots and hoped it would demoralise the citizens.

The Prince of Orange commands the attack on the city of Hulst from his temporary fortress. Medal from 1645, Jan van Loof. From Baums Collection, Künker sale 116 (2006), No. 4247.

In order to conduct a siege, the field commander would first build a fortified camp to protect the army against counterstrikes from the fortress. A trench was dug and the arising soil was used to build a breastwork, maybe even protected with a palisade, where the invaders could retreat to in case of a lunge from those under siege. Chevaux de frise were erected and trapping pits were mustered, deep, partly covered ditches in which a sharp stake was put to impale anyone falling into the pit.

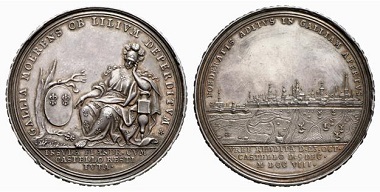

This medal from 1704 on the capture of Landau clearly shows the wickerwork baskets that were used as protection for the canons. From Baums Collection, Künker sale 116 (2006), No. 4556.

Canons were protected by wickerwork baskets filled with soil. This was extremely important, as a targeted shot from the city walls at the gunpowder supplies could do serious damage!

The communication trenches in front of the city are clearly visible. Medal from 1708 on the capture of Lille. From Baums Collection, Künker sale 116 (2006), No. 4228.

The covered communication trenches, which enabled warriors to get close to the city walls safely, were a great advancement. Most mercenaries refused to be part of their construction. Consequently, so-called “Schanzbauern” had to be specially hired, soldiers who would dig ditches into the ground with spades and hacks (colle pala e zappa). These soldiers and their hacks (= zappa) also gave us the word for this technique, sapping, and the word sappers for those who built them. Mines or underground passageways, dug by learned miners underneath the city walls, were another important means to attack. The corridors were then collapsed, taking down the city walls with them.

Sieges lasted long and they were equally gruesome for both the offender and the defender. Fear, hunger, desperation, chicaneries from the soldiers, who were actually meant to protect the city – very rarely can we grasp the distress the civilian population were in. Even if the development of fortresses and siege warfare may sound rather theoretical and sterile here, and even if a shot from a canon looks somewhat decorative on a medal, one must never forget how miserable life in occupied cities was and how brutally an attacking soldier could find his death.

King Louis XIV inspecting a sap himself. From Baums Collection, Künker sale 116 (2006), No. 4047.

The siege war during the era of Vauban (1750-1790)

Until the age of absolutism, cities had taken care of their own fortification. Now, the state took over the costs and responsibility. Louis XIV was the trailblazer for this movement. By reorganising his state finances, he managed to provide enough resources for warfare to extend the power of France far beyond its former borders. His new concept entailed a belt of fortresses along the borders of the new state territory so that the advancement of an enemy could be seen long before they could even enter the actual core country. This would eliminate the danger of devastation and plundering of the most important resources.

It was not only one fortification that protected the city of Strassburg but several of these, featured on this medal from a bird’s eye perspective. From Baums Collection, Künker sale 116 (2006), No. 4049.

In Le Prestre de Vauban (1633-1707), Louis XIV found a congenial architect of fortifications who, in his capacity as Maréchal and in an incredible tour de force, designed a large number of fortifications and plans for their defense. He also came up with plans for their recapture because the new fortifications were not intended to be impregnable. Rather, the goal was to cause the enemy as great a cost and as many casualties as possible when laying a siege. According to the location relative to the frontier, Vauban distinguished 3 lines: the 1st line consisted of blockings of passes and rivers, protected by 3rd system fortifications with five or eight bastioned fronts. Behind was the 2nd line, protected by places of the 2nd system, that is fortifications with at least eight bastioned fronts. The 3rd line was located in the country’s interior. It was intended to serve as deployment zone for entire armies and included fortified cities with more than 12 bastioned fronts. In 1705, Louis XIV possessed 300 fortifications. The single defense installations of the time of the wars of mercenaries had evolved into fortification complex for an entire country.

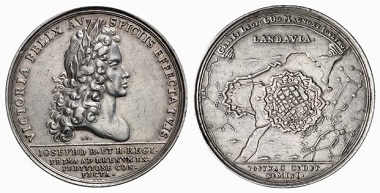

The fortress of Landau was attacked four times in the War of the Spanish Succession. From Baums Collection, Künker sale 116 (2006), No. 4554.

The new fortress required a new kind of attack which was both expensive and time-consuming: It was called a formal siege, for which a set of rules had been established by the time of Vauban. At this point, the art of warfare was a real craft that could be learned from the books. The capture of a city involved three stages: preparation, move towards the main trench, creation of a breach. After preparation was completed, everything required for the siege had to be ready at hand: the troops, the artillery, the material, entrenching tools, ammunition, and provisions. Formulae had been laid down to calculate consumption. For instance, it was believed that for every soldier two defenders were needed. At this stage, information on the fortress had to be obtained, and a map of the city had to be organized. It was deemed essential to gather knowledge about defectors, captives, and spies. Then the weakest spot of the fortification was chosen for the attack. To start a feint attack and fragment the defenders’ forces, a second spot was fired at.

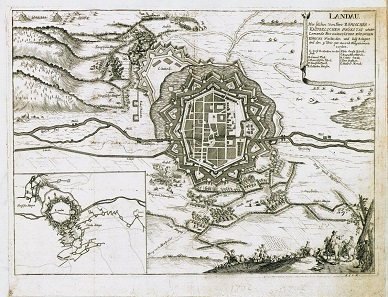

Map of the city of Landau, with the zick-zack-shaped trenches clearly visible in the foreground, dug during the attempt to capture the city. Copperplate engraving of 1702.

The second step involved digging trenches. The attacker protected his camp with two parallel lines, once facing the city to counter breakouts, the other facing outwards, serving as a wall against relieving troops. Originating from the main trench, zig-zag shaped trenches were dug, leading to the city. The first parallel was dug at a 300-meter distance from the fortress’ main trench. A second parallel with further zig-zag-shaped trenches was established up to a distance of 175 meters. Having arrived at a 30- or 40-meter distance from the city with the third parallel, the assault finally began. Meanwhile, preparation of the attack, the artillery had weakened the wall in one or more places. That was there the breakthrough was then made.

The formal handover of the keys constituted part of the ceremonies with which a city surrendered before the assault. Medal 1690 on the capture of Kanischa. From Baums Collection, Künker sale 116 (2006), No. 4410.

The final military step often did not place after all. Because it was easily foreseeable for the defender of a city at what time the assault would take place, he, for being granting free retreat, could surrender to the attacker in advance.

Besiegement in the era of the Revolutionary Wars (1790-1870)

During the French Revolution, not so much the fortifications underwent a change but the art of warfare and of recruitment, related to the French people’s army. For the first time in history, a state had so many instruments of power through the full exploitation of the national strength that it became possible to not only achieve limited war aims, but to conquer an entire country instead. The fortresses thus became less and less important. It was no longer necessary to capture them. They would surrender anyway, once the rest of country was taken. Therefore, the important thing was no longer to achieve a small success by seizing a position but by annihilating the enemy forces on the battlefield. The French were soon emulated: The Prussians and the Habsburgs, too, began to re-organize their forces into a people’s army, following the French model. With this new, powerful army the allied forces marched twice through the famous fortification lines of the city, built by Vauban, in 1814 and 1815 without any major stops.

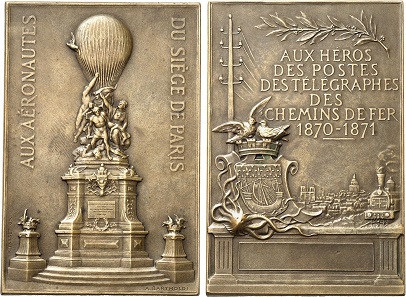

Bronze plaque no date (1906) by P. Tasset on the memorial to the aeronauts killed during the Siege of Paris. From Gorny & Mosch sale 234 (2015), No. 4546.

In the late 19th century, the golden age of the fortifications was over. It became apparent that the air force would usher in a new kind of war fare. In the 19th century, captive balloons were been used for military reconnaissance purposes. In 1870, the French, in besieged Paris, even escaped the siege, using 66 balloons. That put an end to traditional besiegement, as based on the complete blockade of a fortress – and this also concludes our short history of the art of besiegement.

To read the first part, please click here.