translated by Annika Backe

Emperor Ferdinand had chosen the city of Magdeburg to illustrate that he was ready to do everything necessary to implement his Edict of Restitution. Magdeburg was located at the Elbe River, the then main traffic artery connecting the Habsburg territories and the North Sea. There, Ferdinand could not only set an example but, at the same time, assure his position of power.

Magdeburg. 1 groschen, 1629. Coinage struck during the siege. Auction sale Künker 237 (2013), 2301.

The city fathers of threatened Magdeburg immediately started to frantically search for allies. The Swedish king was asked for help, while a son of the neutral, though influential, elector of Saxony was appointed protector.

In the meantime, the emperor tried to appease at least his most important allies, like the duke of Bavaria, by promising him and his family the dioceses of Verden and Minden as long as he, in turn, would accept Leopold, Ferdinand’s later-born son, taking over the dioceses of Magdeburg, Halberstadt and Bremen.

Maximilian did not accept yet, by then, it was all the same to the emperor. The shock and awe approach of Wallenstein’s army proved quite effective in implementing the Edict of Restitution.

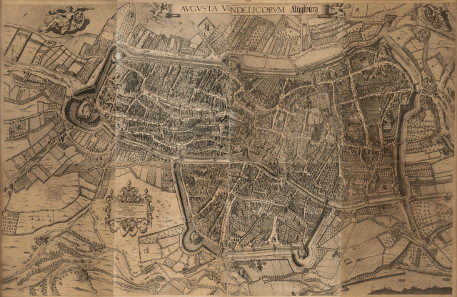

Wolfgang Kilian, city map of Augsburg, 1626. Source: Wikicommons.

In Augsburg, for instance, the entire Protestant clergy was expelled from the city on August 8, 1629, without Ferdinand having to enforce his law by military means. The free imperial city of Augsburg sent 8,000 citizens into exile for fear of the emperor’s military power.

Ferdinand thus enjoyed a position of power like no other German emperor before. Everything seemed possible. Perhaps Germany would soon become an absolutistic state, with the Catholic faith as state religion and the emperor at the top. It was international politics – once again – that crossed Ferdinand’s path.

Sweden. Gustavus II Adolphus. Silver medal, n. y. (1630). On the departure from Stockholm to Germany. Auction sale Künker 249 (2014), 314.

The two beset cities of Stralsund and Magdeburg had asked the Swedish king for his help. Gustavus Adolphus, the “Lion from the North”, as he was nicknamed due to his blond facial hair, was inclined to provide his help – and to expand the territory of Sweden a little bit further. On May 29, 1629, he left Stockholm by ship, after having prevailed in battle against Sigismund III of Poland.

After Christian of Denmark he was the second king from the North who dared to interfere in German matters. Ferdinand could not take this new opponent serious. At that time, he preferred to focus on another territory which the Spanish Habsburgs had an interest in.

It was Northern Italy, the rich territory, where, as it had become tradition, Spain and France were fighting for control – and what was more important: for the revenues. Mantua, for example, was ruled by a French duke. The Spanish, too, would have loved to get their hands on that city. So they asked Ferdinand for his assistance. After all, the Holy Roman Emperor likewise ruled over Northern Italy, nominally at least. That messy situation had a complex background.

In December 1627, Vincenzo II Gonzaga had died, thus terminating the reigning line of the great ruling dynasty.

Charles of Nevers as Duke Charles I Gonzaga, around 1620. Source: Wikicommons.

The Frenchman Charles of Nevers became his successor who, in order to assert his claims, had married the daughter of the penultimate duke to his eldest son in the chamber of the dying duke, only four hours before his death.

Casale Montferrato. Charles I Gonzaga. 20 fiorini, 1630. Auction sale Künker 175 (2010), 2321.

Immediately after the duke had died, Charles had himself proclaimed ruler and asked the emperor to acknowledge the last will of the late duke. Ferdinand II, however, rather pursued his own interests. He was married to Leonora, a daughter of Vincenzo I Gonzaga and intended to exercise his imperial right to seize a terminated imperial fief and to allocate it just as he pleased.

Casale Montferrato. Charles I Gonzaga. Scudo, 1628. Struck on a billon planchet during the siege of the War of the Mantuan Succession. Auction sale Künker 116 (2006), 4122.

Both Mantua and Casale were strategically very important to Northern Italy. As a result, the duke, coming from France, experienced serious difficulties already upon his arrival. Yet Richelieu hoped for the newly-minted duke of Mantua to become a useful ally and provided the financial means necessary to hold the city against the Habsburgs. Late in May 1629, the Habsburg army approached, consisting of 30,000 infantrymen and 6,000 cavalrymen. The siege took 10 months. It ended on July 17, 1630, with the city being sacked. Charles of Nevers managed to escape.

Ferdinand, therefore, was asked to issue an imperial edict that declared Mantua confiscated, thus giving the Spanish a handle to conquer the city. The troops required for such an enterprise were likewise to be provided by Ferdinand.

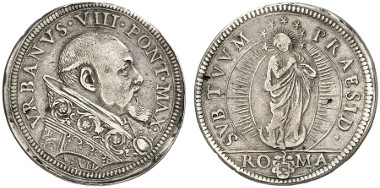

Vatican. Urban VIII. Testone, 1616/1637, Rome. Auction sale Künker 233 (2013), 1373.

By interfering in Italian affairs in such a way, Ferdinand antagonized the pope. He likewise was prince of an Italian territory after all and was afraid that the unstable equilibrium between powers might collapse if the Spanish Habsburgs, assisted by the emperor, were to get major parts of Northern Italy under their control. The pope thus assembled a coalition against Habsburg, consisting of France, Savoy and Venice. That all of a sudden provided France with the support it needed for its project: a siege was laid on the city of Susa, and Casale was liberated.

The Spanish, on the other hand, saw their luck dwindle in Northern Italy. They could not assert themselves in military terms due to their lack of soldiers which they wanted the emperor to finally provide them with. The Spanish Habsburgs wanted to get 30,000 mercenary soldiers from Wallenstein. He, however, refused to send them. According to his enemies amongst the historians, he refused because he did not want to share his power, while his friends believe that he assessed the danger posed by Gustavus Adolphus correctly. What both the emperor and the Spanish Habsburgs realized was that Wallenstein was not the useful tool his employers took him for.

That was the military situation in Northern Italy when the emperor sent an invitation around for a diet, to be held at Regensburg in March 1630. Theoretically speaking, there was peace in the empire in the summer of 1630. That peace, however, was highly deceptive. As top item Ferdinand put the conflict in the Spanish Netherlands on the agenda in which the empire should interfere, as far as the Spanish Habsburgs were concerned. There, too, the Spanish Habsburgs got into dire straits more and more.

Cast silver medal 1630 by A. van der Wilge on the captures of Grol (1627), Wesel (1629), S’Hertogenbosch (1629) and Pernambuco (1630) by stadtholder Frederick Henry of Nassau-Orange and his assistance in capturing the Spanish silver fleet in Matanzas Bay, Cuba. Auction sale Künker 261 (2015), 5802.

On August 19, 1629, Frederick Henry of Orange captured the important border fortress of Wesel, a city that was part of the Holy Roman Empire. A month later, he took the important city of Hertogenbosch. At that time, some adventurous buccaneers managed to capture the ships that transported the pay intended for the Spanish soldiers. Yet no mercenary soldier was willing to continue fighting when he was not being paid. And so the Spanish Habsburgs suddenly found themselves on the defensive. Their relative in Vienna was to bail them out by getting the German electors to declare war on the United Netherlands as a consequence of the frontier violation during the capture of Wesel.

That was not the emperor’s only objective. He planned to talk the elector princes into electing his son Holy Roman Emperor. He, in turn, agreed to dismiss his insubordinate military commander Wallenstein. On August 24, 1630, he sent Wallenstein the discharge papers. It was not possible for him, however, to get his son elected because the prince electors additionally demanded the Edict of Restitution being cancelled which Ferdinand refused steadfastly to do.

The gathered parties likewise did not comply with the Habsburg wish in the Dutch matter. They merely agreed upon Cleves and Jülich becoming a neutral zone from which the emperor and the United Netherlands were to withdraw troops.

But still, Ferdinand managed to negotiate a compromise for Northern Italy which his relatives in Madrid accepted. The status quo from the time prior to the Spanish attack on Mantua was being restored:

Casale Montferrato. Charles I. Silver medal (by J. Warin), n. y. (1630). On the truce negotiated by Papal Legate Cardinal Jules Mazarin. Auction sale Künker 247 (2014), 5301.

By then, the Spanish controlled captured Mantua and returned the city to Duke Charles of Nevers, and were given Casale and Perolo by the French in return.

To the emperor, however, all these problems in foreign countries had more or less begun to take the back seat. Gustavus Adolphus had arrived in Germany and did not prove as benign as he had been taken for.

Read about the intervention of Swedish king in the next episode.

All parts of the series can be found here.