The Spanish Habsburgs had begun to secure the way along the Rhine, which made the United Netherlands feel threatened. After all, in a fight about the Netherlands supplies would have been delivered from north to south rapidly that way. That was why Maurice of Orange decided to support the new Bohemian King Frederick, Elector Palatine.

And so the war continued. Meanwhile, it had moved to Upper Palatinate where Maximilian stormed the city of Cham on 23 September 1620. Mansfeld was forced to flee with his troops.

Frankenthal. Uniface klippe of 15 batzen, 1623. Ehrend 9. From auction sale Künker 131 (2007), 5088.

He went for Rhenish Palatinate and passed – without intervening at all – Frankenthal on 25 October 1621, where the English troops under Sir Horace Vere were beleaguered by the Spanish. He intended to take up winter quarters in wealthy Alsace. And there he waited for Frederick V to form a new army with the help of the Netherlands.

Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Principality. Christian, Bishop of Halberstadt. Reichsthaler, Lippstadt, 1622 (so-called Pfaffenfeindthaler). Dav. 6320. From auction sale Künker 237 (2013), 2654.

As a matter of fact, Frederick had found himself a number of new allies. One was Christian of Brunswick, administrator of the Bishopric of Halberstadt, younger brother of reigning Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. He seemed to have been an ardent religious warrior who was completely unpredictable when it came to the Protestants’ matter. His unconventional fanatism brought him the nickname ‘mad Halberstadter’. Albeit he didn’t have enough means to form and maintain an army. It was the war that nourished his mercenaries. Thus, the Libori shrine and other religious equipment he got his hands on when Paderborn was sieged on 30 January 1622 was melted down and coined. The motif on the coins – and its radical propaganda was actually a true novelty – interprets the action of the military commander: against the official church, for the good of those who want to turn to God directly. Already the contemporary writers discussed and commented on the coin themes of the ‘Pfaffenfeindthaler’, and when Christian of Brunswick lost his left arm in the Battle of Fleurus the Catholics considered it God’s vengeance. The propagandistic success of the ‘Pfaffenfeindthaler’ was huge; as a matter of fact, it was so big that Christian continued minting these coins long after he had already run out of silver he had gained from melting down the Libori shrine.

Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Principality. Christian, Bishop of Halberstadt. Reichsthaler, Lippstadt, 1622 (so-called Pfaffenfeindthaler). Dav. 6322. From auction sale Künker 116 (2006), 4510.

With almost absolute certainty he was the one responsible for the draft of the second thaler type that expresses the concern of the ‘mad Halberstadter’ even more drastically. On that type, the biretta as the head gear of the Jesuits is speared with the sword. There are, however, only a few contemporary patterns of that type extant. The majority is likely to date to later times: in 1670/71, Christoph Bernhard of Galen, Prince-Bishop of Münster, could accuse Rudolph Augustus, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, of deliberately producing ‘Pfaffenfeindthaler’ restrikes to stir up confessional hatred. Restrikes were produced right into the 18th century.

Baden. Baden-Durlach, Margraviate. George Frederick. Reichsthaler, 1622. Dav. 6045. From auction sale Künker 95 (2004), 3273.

George Frederick, Margrave of Baden-Durlach, became his second ally and he brought his army with him so that Frederick finally had as many as three armies at his disposal: Mansfeld in Alsace, Christian of Halberstadt with Frederick V in Westphalia and George Frederick in Baden. The three armies, however, were located at places far too far apart from each other to operate efficiently. Thus, the first aim was to unite. The first aim of the Catholic troops commanded by Tilly then became crystal clear: they had to try to prevent that union.

Pieter de Jode II after Anthony van Dyck, portrait of Johann t’Serclaes von Tilly, around 1630. Source: Wikicommons.

When the Neckar was crossed, there was first contact with the enemy. Mansfeld managed to get to the other side of the river with his troops. George Frederick of Baden-Durlach, on the other hand, faced Tilly which resulted in a battle. Prior to the fight, Margrave George Frederick had been of idealistic nature and never needed to face the real events of such butchery. His defeat wasn’t that overwhelming. He could have tried to recollect his forces to try his luck a second time. But George Frederick wasn’t willing to shed the blood of his natives for the cause of the Protestants. He retreated, being utterly disillusioned, and henceforth eschewed war-related events. It is tempting to reflect upon which course the Thirty Years’ War might have taken if more rulers had prioritized the good of the citizens entrusted to them over their own dynastic plans.

That made only two armies remaining for Frederick V he could make use of in order to regain the Palatine: the troops of Mansfeld and the soldiers of Christian of Halberstadt. Consequently, Tilly and Mansfeld had a race going on: Mansfeld wanted to unite his army with the one of Christian, while Tilly intended to defeat one of the two enemy armies before they would have the edge over Christian’s troops thanks to their power being united.

Tilly won the race. His well-organized army was quicker than the ill-disciplined troops of Mansfeld that were in constant need of finding fodder during the march. The Catholic army was provided by Christian of Halberstadt when he crossed the Main.

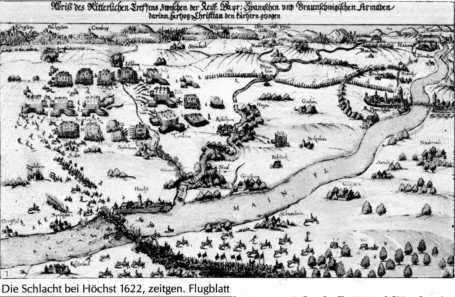

The Battle of Höchst in a contemporary depiction, 1622. Source: Wikicommons.

Not far away from Höchst a battle was fought in which Tilly managed to cause the troops of the ‘mad Halberstadter’ a great number of casualties. What he didn’t achieve, however, was to stop the Protestant army. Christian of Halberstadt crossed the Main and met Mansfeld a little bit later. The forces united and, after passing Landau, turned towards Alsace.

Prior to this campaign, Frederick V, too, had envisaged the war to be somewhat different. The actual occurrences, the lootings and rapes, the atrocities and the killing of innocent people, the starvation and the despair of the ones left behind, the ruins of the houses burned to the ground and the corpses that were soon lying unburied everywhere in the country horrified the Count Palatine to such an extent that he terminated the contract with Christian of Halberstadt and Mansfeld for the retrieval of his lands on 13 July 1622. Without an army, Frederick V retreated to his uncle, Duke of Bouillon, to Sedan.

In the next episode you will read about the circumstances of the rise of one of the best-known protagonists of the entire Thirty Years’ War: Wallenstein.

You can find all parts of our series here.