Spain prepared a military action against the United Netherlands and Ferdinand II – thanks to the lack of an election rival – managed to get elected King of Bohemia. That was the point of departure. When the mainly non-Catholic subjects of Bohemia felt neglected by their new and over-Catholic ruler they searched for an opponent and found him in Frederick V, Elector Palatine, who immediately sent his military commander Mansfeld.

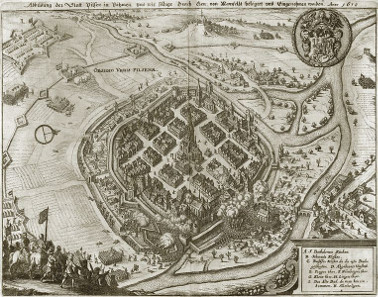

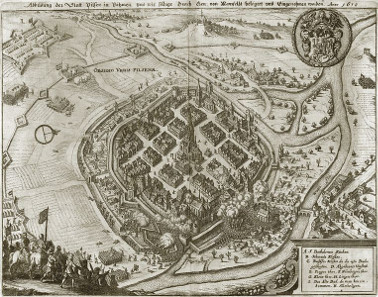

Matthäus Merian, seizure of the city of Pilsen by an army of the estates commanded by Mansfeld on 21 November 1618, prior to 1635. Source: Wikicommons.

The troops of the House of Habsburg went for Budweis while Mansfeld besieged Pilsen and finally took it on 21 November 1618. Thus, the Spanish troops were trapped in Budweis and Bohemia was saved from the Habsburg grip – for the moment at least.

After Ferdinand, in his function as Bohemian king, had run into opposition to such great an extent, Fredrick V, Elector Palatine, hoped positively for the Bohemian crown. In order to make sure of the support of the Protestant estates, he called a gathering of the Union whose leadership he had inherited from his father. The Union was an informal coalition of the Protestant states of the empire. Frederick V in all probability presented them the prospect of the huge possibilities for the common goal once the Bohemian crown had been won: after all, the German emperor – just like the Bohemian king – was chosen in an election. Seven prince-electors were charged with the task of electing him. Three of them, the archbishops of Cologne, Mainz and Trier, were Catholic ex officio and were highly likely to favor an emperor of Catholic faith.

The count palatine of the Rhine, i.e. Frederick, was Calvinist, just like the margrave of Brandenburg. In addition, there was John George I of Saxony, who was of Protestant faith. That made three reliably Catholic prince-electors against three reliably Protestant ones. Hence, it was the king of Bohemia to tip the scales – he used to be a Catholic Habsburg but when he, Frederick, would be elected king of Bohemia, there was some likelihood that this relationship might turn and a Protestant prince might get the chance of becoming the next emperor. Despite of that tempting speculation, the Union advised Frederick V to reach an agreement with Ferdinand. So, that party would provide no support for winning Bohemia. Nevertheless, the Bohemians favored the elector palatine as new king. They relied on the magnificent international connections their pretender to the throne possessed. He was the son-in-law of the English king and enjoyed the financial backing from the Dutch who hoped for the Palatine, who was ruled by him, acting as a barrier for the Spanish supplies.

Margraviate of Moravia. Moravian estates. Kipper-12 kreuzer, 1620, Olmütz. HALACKA 597. From auction sale Busso Peus Nachf. 394 (2007), 3871.

The death of the old emperor Matthias on 20 March 1619 resulted in a radicalization of Bohemia – and disturbances in other Habsburg lands. There was an open revolt in Moravia; rebellions were simmering both in Upper and Lower Austria as well as in Carinthia, Carniola and in Styria. The troops of the Bohemian estates first cleared Moravian of all sympathizers of Ferdinand, to turn towards Vienna afterwards. In the meantime, an open discussion had begun about the question whether or not Ferdinand, who was the one responsible for the revolt in Bohemia, was suited for Holy Roman Emperor at all.

Abraham Hogenberg, Battle of Sablat, 1619. Hogenbergsche Geschichtsblätter, around 1630. Source: Wikicommons.

Amidst all that turmoil, in all those ruins of his policy collapsed, Ferdinand was only one who remained calm. Seemingly devoid of all emotions and full of confidence he waited for the change fate would certainly bring. And change there was. In the Battle of Sablat, on 10 June 1619, Mansfeld suffered defeat with his army that Ferdinand had financed, and the council of the estates ordered the troops in front of Vienna to return to Bohemia at once.

That happened just in time, because at the end of July, the elector princes met in Frankfurt to elect a new German king. That event triggered feverish activity in Prague. Ferdinand had to be unseated before he would cast a ballot at the election of king in that function. On 31 July 1619, Bohemia united with Lusatia, Silesia and Moravia to form an alliance. On 19 August, the estates of the allied territories declared Ferdinand’s election as King of Bohemia null and void.

Gabriel Bethlen, Prince of Transylvania, 1613-1629. Ducat 1622, Nagybanya. Künker 239 (2013), 5483.

On 20 August, an agreement was signed between Moravia and Bethlen Gabor. This Bethlen Gabor, a militant prince in Transylvania, had attacked another ancestral homeland of the House of Habsburg before, i.e. Hungary, and had been quite successful there.

Finally, on 26 August 1619, Frederick was elected Bohemian King with 100 votes against John George of Saxony who won only 46 votes. Two days later, the German king was elected – and Ferdinand participated, despite the strong protest of the Bohemian estates not only as candidate but as elector palatine because Frederick V hadn’t assumed office yet. Hence, Ferdinand was sure of his own vote, and in addition he got the votes of the arch bishops of Cologne, Mainz and Trier. King John George of Saxony likewise voted in favor of Ferdinand, just like the representatives of the margrave of Brandenburg. That made the representatives of Frederick as elector palatine the only ones who hadn’t balloted yet. At first, they tried to bring another candidate into play, Maximilian of Bavaria. But when Maximilian withdrew in favor of Ferdinand the representatives were left no choice as to give the Palatine vote to the one and only candidate, hence Ferdinand.

Frankfurt. Medal on Ferdinand II being elected German emperor. Förschner 48. From auction sale Künker 242 (2013), 3508.

By that, the ironic situation had arisen that Frederick V competed with a man for the Bohemian crown that had got elected German emperor thanks to his ballot.

Bohemia and Moravia. Friedrich V, Elector Palatine. Silver medal, 1619. On Frederick being crowned King of Bohemia. Doneb. 2029. From auction sale Künker 228 (2013), 3407.

On 28 September 1619, Frederick V accepted the Bohemian crown and, in doing so, dashed all hopes for an accommodation for the time being. At the top of his troops he went for Bohemia and left his ancestral homeland in the Palatine completely defenseless. In autumn 1619, things in Bohemia still looked good for him: Bethlen Gabor had united his forces with the Bohemian ones and had taken Pressburg. The Habsburg troops were forced to retreat over the Danube, and the allied forces commanded by Gabor started a second march towards Vienna. Several foreign powers, including the United Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden and Venice, recognized Frederick V as King of Bohemia.

Saxony. John George I. Silver medal, 1619. Merseb. Coll. 902. From auction sale Künker 242 (2013), 3613.

From the Protestant Union came no support whatsoever – John George of Saxony even assured the emperor and the Bohemian king of his backing this breach of the imperial constitution. Frederick likewise hoped in vain for the assistance of his father-in-law. And soon, it became more and more difficult to finance the payment of the army of mercenary soldiers led by Mansfeld. The 50,000 gulden per month that the United Netherlands paid as subsidies were a mere drop in the bucket. As if that weren’t enough already, Bethlen Gabor was forced to abandon the siege of Vienna because he received word about riots in his native country Transylvania.

When Bohemia ran short of money, it seemed that Ferdinand had been victorious and the war terminated. The questions of power, however, had become much too muddled, and all of a sudden Ferdinand’s ally Bavaria turned into an obstacle, and likewise the other Protestant powers didn’t back down that easily…

You can find all parts of our series here.