translated by Annika Backe

Immediately after the death of Wallenstein, Archduke Ferdinand was given supreme command of his army. The commanders Matthias Gallas and Octavio Piccolomini were his direct subordinates. That made two Catholic armies. The one Wallenstein used to lead, now under the command of Archduke Ferdinand, and the army of the cardinal-infante who advanced from Italy, accompanied by 20,000 soldiers. The other side had three Swedish armies at their disposal, one led by Gustav Horn, the other by Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar, as well as a joint army led by Landgrave William of Hesse-Kassel. Furthermore, there were the military forces of John George of Saxony under the command of Arnim.

Portrait by an unknown painter depicting the Swedish military commander Gustav Horn (left-hand side) and Bernhard of Weimar as military commander. In the background the city of Würzburg with Marienberg Fortress to the left and Breisach am Rhein to the right. Copper engraving by Johann Dürr (Augustanus), sketched by Christian Richter. From the so-called Electors’ Bible, published by Wolfgang Endter in Nuremberg in 1641. Source: Wikicommons.

On July 12, 1634, Gustav Horn joined his forces with the ones of Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar, to annihilate the troops of inexperienced Archduke Ferdinand before he, in turn, could join the cardinal-infante. The two commanders did not get along very well because both hoped to be given supreme command over the joint military forces of the Swedes.

Minden. Klippe worth 8 groschen, struck during the siege, 1634. Auction sale Künker 87 (2003), 4205.

In the wake of what happened during the Thirty Years’ War, the siege of Minden was taking place, laid on the city by the troops of Duke George of Brunswick-Lüneburg from July 24 to October 24, 1634. Neither the Habsburgs nor the Swedes had an interest in participating in that rather local affair. After a three-month siege, then, the imperial occupying troops, under the top one of those of Waldeck, surrendered their city to the duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg.

Back to the main events: both commanders, Gustav Horn and Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar deemed the moment opportune. They had learned that the Saxon army, led by Arnim, had invaded Bohemia. They hoped that the archduke would retreat to Bohemia in order to protect his country. But although Arnim was standing at the city walls of Prague, the future emperor was not willing to turn around. He continued marching towards Regensburg and recaptured the city that had been lost only recently. On August 16, 1634, the troops crossed the Danube River not far away from Donauwörth. It took the archduke only a couple of days to retake that city as well.

Germany. Würzburg. Reichsthaler n. y. (1633/1634). Under Swedish Lord High Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna. Auction sale Künker 208 (2012), 7544.

The triumphal march of the young archduke added spice to the discussion the members of the Heilbronn League were having during their meeting in Frankfurt. They had been highly suspicious of the suggestions coming from Oxenstierna before. The Protestant prince electors were upset by the fact that he had ceded demesnes on German territory to numerous soldiers in the service of the Swedes – for example, Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar’s request for Franconia was granted. It seemed that the Swedish chancellor conferred German demesnes at will – just like the emperor used to do. The French envoys took advantage of the participating prince electors being uneasy. They offered lavish subsidies for as long as the war would take and demanded the fortress of Philipsburg as security. In 1622, Philipp Christoph had fortified Udenheim, near the city of Speyer, for which Philipp served as eponymist. That fortress likewise harbored the recently established mint (operating between 1623 and 1632) and the bishop in those uncertain times. The Swedes as occupying troops, however, were not inclined to give the fortress of Philippsburg away.

Diocese of Speyer. Philipp Christoph Freiherr von Soetern. Gold gulden, 1632, Philippsburg. Auction sale Künker 234 (2013), 3991.

After Donauwörth had been lost, though, the allies made Oxenstierna sign a treaty on August 26, 1634, stipulating the surrender of Philippsburg to France, in return for corresponding subsidies. As his commanders and generals, Oxenstierna was perfectly aware of the fact that he could only remain in control in the Heilbronn League as long as the Swedish troops were on the front foot. Hence, Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar and Gustav Horn had no choice than to try to relief the city of Nördlingen which, in the meantime, the joined troops of the cardinal-infante and Archduke Ferdinand had begun to besiege.

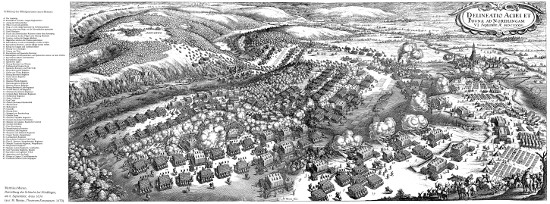

Matthäus Merian der Ältere, depiction of the Battle of Nördlingen, on September 6, 1634, 1670. Source: Wikicommons.

September 6, 1634, was the day of battle. In the end, the Swedes had to accept a crushing defeat. Together with 4,000 soldiers, Gustav Horn was taken prisoner. 17,000 mercenary soldiers lost their lives. Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar had to surrender his only recently gained rule over France. He withdrew from Württemberg. All Swedish garrisons were ordered to proceed to the Rhine River to hold the Rhine boundary at least. By that, the front line had moved backwards by 240 kilometers. The Battle of Nördlingen resulted in the Swedes losing their leading part in the war. That made France, and the Bourbons along with it, the key figures in the fight against the Habsburgs.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Victory of the Two Ferdinands, 1634/1635. Source: Wikicommons.

After the Battle of Nördlingen the two young military leaders of the Habsburgs agreed on going separate ways again. The cardinal-infante still intended to recapture the Netherlands, while Archduke Ferdinand’s plan was to tidy up Southern Germany first. And that was what he did, successfully almost everywhere. On September 15, 1634, he took Göppingen, on September 16, Heilbronn, on September 18, Waiblingen, and on September 20, Stuttgart.

The cardinal-infante, in turn, went north. The cities that surrendered to him were Rothenburg on September 18, 1634, Nuremberg on September 23, Aschaffenburg on September 30, Schweinfurt on October 15, and Würzburg on October 21.

Frans Luycx, Portrait of John George of Saxony, 1652. Source: Wikicommons.

As was to be expected, the military weakness of the Swedes caused many of their allies to turn to the emperor again. The leading role was assumed by John George of Saxony. The two parties, the emperor and the powerful prince elector, made a serious attempt to establish a basis for peace. Ferdinand II was even inclined to let go of his most important project, the Edict of Restitution, to finally generate a sound basis for a truce. The peace treaty was signed on February 28, 1635.

Read in the next episode how clever Cardinal Richelieu supported the enemies of the Habsburgs in his attempt to weaken Ferdinand.

All parts of the series can be found here.