translated by Annika Backe

The death of Gustavus Adolphus could have been another chance for peace. Furthermore, not only two weeks after the Swedish king had died, the one figure passed on because of which the Thirty Years’ War had broken out in the first place: Frederick V succumbed to the plague at Bacherach am Rhein.

Three parties, however, considered their war objective not yet achieved. The Dutch hoped for bigger territorial gains along the Rhine River as long as the Spanish Habsburgs were that weak. The Spanish Habsburgs, in contrast, were not inclined to start peace negotiations, being in a weak position. In addition, Swedish chancellor Axel Oxenstierna was horrified by the prospect that he was compelled to show up in the parliament at Stockholm, to provide a justification of the high sums of money and the incredibly number of lives the war in Germany had cost Sweden. He needed greater successes in order to end the war with a victory.

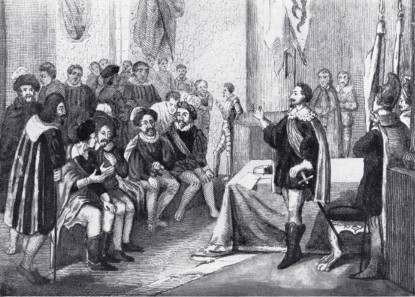

Axel Oxenstierna negotiating with representatives of the Heilbronn League on April 23, 1633. Colorized lithography, around 1842, after a contemporary copper engraving. Source: Wikicommons.

But first of all, Axel Oxenstierna had to make sure that his allies would support him even though Gustavus Adolphus was dead. He gathered the allies of Sweden at Heilbronn, on March 18, 1633. They appointed him commander of the military actions of the newly established Heilbronn League. At that congress, France managed to become acknowledged as protector of the Protestant cause. Apart from that, Oxenstierna had to accept the fact that France was paying its subsidies no longer into Swedish state coffers but to the Heilbronn League instead.

Gaspar de Crayer, portrait of Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand of Spain as cardinal and archbishop of Toledo, 1639. Source: Wikicommons.

In Spain, at about the same time, the office of governor of the Netherlands was conferred upon a man who was young and fresh. Ferdinand was the third son of the Spanish king who wished him to make an ecclesiastical career. He was thus anointed cardinal, which is why contemporary sources refer to him as ‘cardinal-infante’. In a triumphal procession and together with his army, this cardinal-infante wanted to return to the Spanish Netherlands that had lost many of their territories to the successful United Netherlands.

Stadtholder of the Northern Netherlands. Frederick Henry of Orange. Silver medal, 1632. On the capture of Maastricht. Auction sale Künker 247 (2014), 5379.

Venlo, Roermond and Maastricht had fallen in 1632 and the young man intended to patch things up. He imagined it to be a relatively easy task. A big army was to be assembled in Northern Italy. According to his plans, the army would then march northwards along the Rhine River and invade the Spanish Netherlands. This would make a good opportunity to likewise liberate the territories seized by the Protestants.

Naïve though that plan was, the cardinal-infante was nevertheless backed by his brother-in-law, Ferdinand who, as Ferdinand III, was to become Holy Roman Emperor later. To avoid any confusion with so many Ferdinands involved, we would like to say Ferdinand II when referring to the emperor from now on, Archduke Ferdinand when his son, the future emperor is meant, and cardinal-infante when we speak about the Spanish Ferdinand.

Anonymous court painter, equestrian portrait of the archduke of Austria as Ferdinand III, 17th century. Source: Wikicommons.

At the royal court, Archduke Ferdinand was leading the party that was hostile towards Wallenstein. These were his plans: in order to come to the rescue of his brother-in-law, the cardinal-infante, he needed an army, which, however, the court could not fund at that time. That was why the unreliable Wallenstein had to be stripped of office so that he, the archduke, could take over his army. Archduke Ferdinand never doubted his ability to lead his army to victories for a second.

In all likelihood, Archduke Ferdinand would not have been able to form a sound coalition to support his plans had it not been for Vienna’s general impression that the general had become a loose cannon. The request of the emperor notwithstanding, Wallenstein refused to aid Maximilian of Bavaria. All he did was to send observers to Eger that were to report to him when something happened in Bavaria.

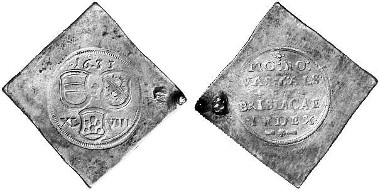

Germany. Breisach. Klippe of 48 kreuzer, struck during the siege, 1633. Auction sale Künker 84 (2003), 3667.

When Breisach as the most important fortress at the Rhine River, securing the way north for the Spanish troops, was threatened by the Swedes as well, the emperor and his Spanish allies saw no other option than to neutralize Wallenstein and to begin negotiations with Wallenstein’s field marshal Aldringer. He promised to raise a contingent of troops, against his supreme commander’s express will. On September 29, 1633, Aldringer joined forces with the Spanish army near Ravensburg. On October 3, the besieged city of Constance was freed, and on October 20, Breisach was relieved.

The crushing defeats at the Rhine River and Lake Constance made the Swedes proceed to Bavaria again. They advanced towards Regensburg, the important fortress located at the connecting line to Austria. Again, the emperor turned to Wallenstein and begged for help. And again, all he received in turn were cynical replies of the exhausted and gout-stricken military commander who nevertheless was bound and determined to not change his mind. On November 14, 1633, Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar, ally of the Swedes, invaded Regensburg. Six weeks later, on December 31, 1633, Vienna made the decision to get rid of Wallenstein. On January 24, 1634, the emperor signed a patent removing Wallenstein from office. He did not send it to his commander. Instead, he wrote to Mathias Gallas and ordered him to consult with Octavio Piccolomini in order to devise a plan how to relieve Wallenstein of office without causing the army to revolt. After all, Archduke Ferdinand needed the troops in full strength to assist his brother-in-law, the cardinal-infante, in re-capturing the Spanish Netherlands.

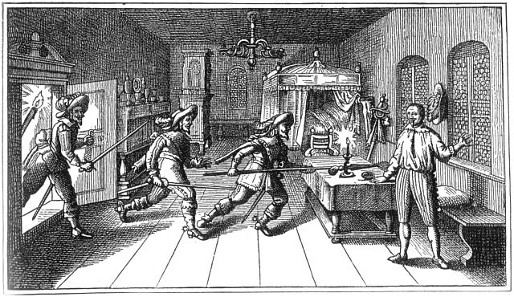

The assassination of Wallenstein at Eger, after a contemporary copper engraving. Source: Wikicommons.

We do not want to recall what has been told any number of times before. On February 22, 1634, Wallenstein fled from his own army whose loyalty he could no longer take for granted. On February 25, he arrived at Eger and was killed by the commander of the fortress and a Colonel Butler whom he had compelled to accompany him on his escape. Curiously enough, the army was not shaken by his assassination. All of Wallenstein’s soldiers, except for only a very small number, declared themselves loyal to the emperor. Ferdinand II did not even have to extend the punishment of Wallenstein to his family. He left Wallenstein’s heirs with his estate, hoping for the organization, which generated so much means for funding the army, to remain intact.

In the next episode you are going to read how the tide is turning and how the Swedes are driven back steadily.

All parts of the series can be found here.