By

With the kind permission of the MoneyMuseum

Our series ‘The People of Zurich and their Money’ takes you along for the ride as we explore the Zurich of times past. This time, you’ll get a chance to read about two men chatting with one another at the customs station of Turicum at the end of the 2nd century AD. Much like a good DVD, this conversation comes with a sort of ‘making of’ – a little numismatic-historical backdrop to help underscore and illustrate this conversation.

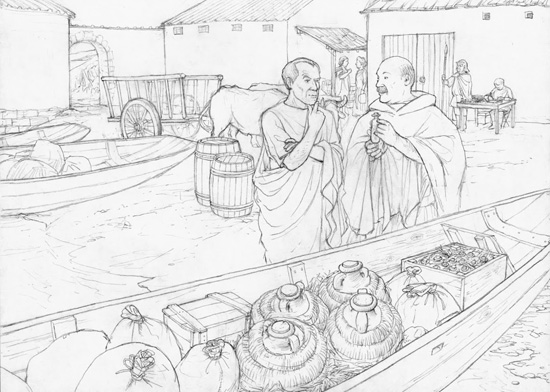

The end of the 2nd century AD. Marcus, a Roman trader, is declaring his cargo at the customs station of Turicum and gets into a conversation with Unio, the Roman customs official. Drawn by Dani Pelagatti / Atelier bunterhund. Copyright MoneyMuseum Zurich.

Marcus: Hallo Unio, how are you?

Unio: Hallo Marcus, good to see you. You’re travelling to the North?

No, I’m not going to Colonia Agrippina this time. I’ll bring my freight to Lugdunum.

Nevertheless, you have to pay your duty. Both Colonia and Lugdunum are located within the Gallic customs district.

That’s right. You Roman officials always want to take care of us – (laughs) and of our money.

Listen, the Roman administration does a lot to deserve your duties. Didn’t you travel on well kept roads?

Yes, but…

Did brigands or barbarians attack you?

No, but…

You wouldn’t be able to carry on trading, if the emperor didn’t take care of the security of the roads.

Yes, you’re right, but most of my money is spent in Rome. I have to work hard and the emperor uses my duties to feed and to amuse some indolent Roman citizens. The whole Roman tax system is made to stuff the city of Rome.

Those days are over. Today the emperor really takes care of the Roman provinces. Just think of…

(interrupts him) All right, all right. I’ll pay the 2.5 percent duty for my goods.

So, what do you bring with you?

The usual: 1,000 modii of grain and 100 modii of olives. Some incense: 100 pounds of the cheapest, the middle and the best quality. Besides that I have 150 phials of perfume from Sardeis with me.

Genuine Lydian perfume? That’s expensive.

Not at all. It’s in very small phials.

You just want to bargain! Let me work it out: 1,000 modii of grain – does it contain the spelt?

No.

That comes to 48 asses selling-price per modius, altogether 3,000 denarii. Then 20 amphorae of olives? Normal quality?

Yes.

So that makes 125 Denarii. 100 pounds of cheap incense comes to 300 denarii, of the middle quality to 500 and of the best quality to 600 denarii.

For the perfume you have to quote 2 denarii per phial at the most.

Listen, I’m married man, I know what perfume from Sardeis costs.

It’s filled in really small phials!

Show them to me. That’s what I thought, the phials are five times as large as usual. I’ll have to calculate 10 denarii per phial.

Blood-sucker!

That comes to 3,000 denarii for the grain, 125 denarii for the olives, 1,400 for the incense and 1,500 denarii for the perfume. That’s 6,025 denarii altogether. You have to pay a duty of 150 denarii and 2 sesterti.

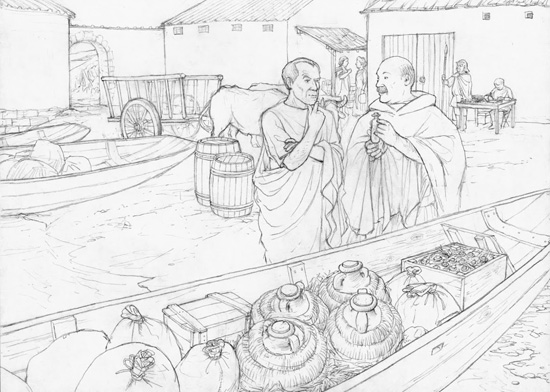

A replica of the Roman gravestone on Pfalzgasse in Zurich, found in 1747 on the Lindenhof. It features the oldest reference to the Latin city name “Turicum” in the form of the adjective Turicen(sis). The original is in the Landesmuseum (Swiss National Museum). CIL XIII, 5244. Source: Roland zh / Wikipedia.

Making of:

On May 18, 1747, the gravestone of Lucius Aelius Urbicus was found in Zurich. It had been erected by his father, an imperial freedman named Unio Aelius Urbicus, who acted as head of a customs station. As such, he was responsible for collecting the Quadragesima Galliarum, a 2.5 % tax imposed by Rome on all imported goods crossing the borders between the Illyrian and Gallic customs regions. The Illyrian region comprised Noricum and Pannonia, while the Gallic region consisted of the four Gallic and the two Germanic provinces. Raetia was shared between the two areas. It was forbidden to cross over this border illegally. To prevent any illicit activity, military posts with policing functions monitored the streets for traders who might attempt to find clever ways to bypass and elude the customs station. There were official customs offices in Acaunum / St. Maurice VS, Genava / Geneva and in Zurich, then called Turicum.

The inscription on the gravestone dates back to around the end of the 2nd century AD. At that time, Turicum was little more than a modest garrison where various merchants, craftspeople and, above all, service providers in the transport industry had settled. This was because Turicum was where goods that had been shipped via Lake Walen and Lake Zurich had to be reloaded for transport by land. Its strategic location was also why the Roman administration maintained a customs station here – it was easier to monitor the turnover of goods at locations that merchants could only avoid at great expense of time and money.

Anything that promised to turn a good profit was dealt in and traded. Experienced merchants preferred to deal in mixed cargo, thus keeping their risk of loss to a minimum through a broad distribution of offers. Bulk goods like grains, which formed the basis of the Roman diet, were also transported. Since not all cities generated enough grain on their own to feed their citizens, the grain trade offered a relatively secure potential for profit. Frankincense was also a highly in-demand commodity, as everyone needed it for their daily incense offering to the gods.

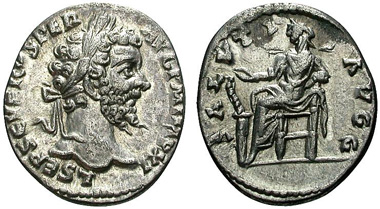

Septimius Severus, 193-211. Denarius, Eastern Mint (“Laodikeia”), 198. BMC 281, 629. RIC 159, 497a. C. 642. From Münzen und Medaillen auction 30 (2009) 1315.

Although the customs officer in the dialogue is still extolling the virtues of the safety of Roman roads in the far-lying provinces, the fact is that the ‘golden age’ of the 2nd century AD was drawing to a close. The first offshoots of the Migration Period were affecting the borders of the Roman Empire. The Civil War of 197 had already negatively impacted the western provinces – the decisive battle between Septimius Severus and Clodius Albinus took place at the final destination of our fictional trader, at Lugdunum, now Lyon. The first clashes with the Alemanns began around 213 AD, which obviously adversely affected long-distance trade. While our fictional merchant was able to move about the Roman Empire casually and carefree, his descendants would have to wait another one and a half millennia to be able to do the same.

Next time, we’ll listen in on the market in Zurich during the 13th century to get an idea of the problems that exchanging money caused in those days.

You can find all other parts of the series here.

The texts and graphics come from the brochure of the exhibition of the same name in the MoneyMuseum, Zurich. Excerpts with sound are available as video here.