translated by Annika Backe

No matter what Irish coin of modern times you have at hand, every single one of them features the coat of arms of Ireland, the gold harp on a blue field.

The Irish 1-euro coin. Photo: EZB.

With this harp, Jarlath Hayes who designed the motif of the Irish euro coins, embraces a symbol that is linked to the Emerald Isle since the Middle Ages.

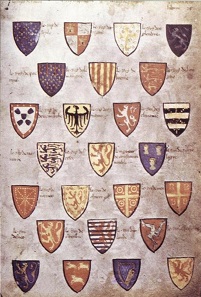

The Wijnbergen Roll, an armorial from the High Middle Ages.

The harp

The oldest extant source of the gold harp as the Irish coat of arms dates from the 13th century. Known as Wijnbergen Roll to academics, the armorial was made around 1280. Today held in The Hague, it bears a description of the very coat of arms as being the one of the Kings of Ireland.

Thus, the harp stands out from all the lions, eagles, falcons and castles, placing Ireland in a special position. Heraldics only knows one other coat of arms that consists of a harp prior to the 19th century.

Tristan and Isolde. Oil painting by Edmund Leighton, 1902.

Why is the harp linked to Ireland so strongly? Some scholars think literature responsible: One possible explanation centers upon the poetry of a Gaelic bard speaking of a musically talented King of Thomond, or the popular medieval story about Tristan who, as the bard Tantris, comes to the King of Ireland, to ask for Iseult on behalf of his foster-father Mark.

But is there any need for reasons for choosing the harp other than the love of singing for which the Irish people are renowned for up to the present day? Why shouldn’t this national characteristic have survived until the Middle Ages?

The Brian Boru harp, currently housed in Trinity College. Photo: Marshall Henrie, CC-BY 3.0.

The Brian Boru harp

The shape of the featured harp is reminiscent of a medieval musical instrument, held in Trinity College, Dublin. It dates back to the 14th or the 15th century, which per se renders any connection with Brian Boru, High King of Ireland at the turn of the centuries, impossible. That didn’t hinder generations of Irish people from regarding the archaic instrument as the harp of Brian Boru though, the popular fighter against the Vikings. This powerful warrior not only united Ireland. He was also a great singer who is said to have accompanied himself on his harp.

When Brian Boru and his son died in the decisive, victorious, final battle against the Vikings, a battle as it was known only from the songs of heroes, three bards allegedly sang dirges at the tomb of the King for three entire days. Perhaps it is this tradition that links the royal name with one of the oldest tunes in Ireland’s traditional musical repertoire: Brian Boru’s March.

John Derrick, The Image of Ireland, published in 1581. The chief of the Mac Sweynes seated at dinner.

Part of the English coat of arms

Strictly speaking, it had been Henry II who had begun to make the Emerald Isle subject to his rule in 1169. He successfully installed his thanes in the eastern part of the island. Therewith, Henry Plantagenet reached the height of his power. And he intended to subjugate the whole of Ireland to Norman control. His sons, Richard the Lionheart and John Lackland, though, were not of the same caliber. Adding to this, the Irish caused trouble. They had developed their own forceful identity from quite early on, and at the first sign of weakness on the part of the London-based ruler, the proud Irish reclaimed their liberties.

The Hundred Years’ War in which the English King fought in France, and then the dreadful Wars of the Roses banished Ireland to the margins of public interest.

Henry VIII, 1509-1547. Groat no date (1534-1540), London. The crowned monograms of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour on the right and the left of the Irish coat of arms. From Künker sale152 (2009), No. 5279.

This only changed when Henry III faced an open rebellion by the Fitzgeralds. The Fitzgeralds were one of the most powerful Irish families. Some of their members had even acted as royal deputies and married into the royal family. They rivalled with the Ormonds in a bitter dispute. One of the Ormonds had gained the favor of Henry VIII and thus was in the position to publicly accuse his old enemy. The head of the Fitzgeralds had to justify himself in London. He was thrown into the Tower, while at home rumors were spreading that he had been executed – a fate all members of the family would be facing. The Fitzgeralds started a rebellion. That didn’t receive enough support from the population, though, to prevail against the troops of Henry VIII. Henry turned out victorious, and he decided to bring the entire island under his control, once and for all, to prevent it from becoming the point of origin of a hostile invasion.

In 1541, Ireland was officially incorporated into the Kingdom of England. Some coins of Henry VIII, known to numismatists as ‘harp coinage’, bear testimony to this.

James I, 1603-1625. Crown no date (1604/5), London. From Künker sale 254 (2014), No. 2206.

James I officially integrated the Irish harp into the English coat of arms – and for this we also enough numismatic evidence.

Coat of arms of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Source: Wikipedia / Sodocan. CC-BY 3.0.

Until the present day the official coat of arms of the United Kingdom proclaims that Ireland forms a part of this union of countries.

Copper pattern for 1/2 crown 1927. From Künker sale 183 (2011), No. 1750.

When a part of Ireland became independent in 1922, the Irish Free State proudly adopted the old harp as their emblem. And right until the present day many people still link Ireland with its music, the multitude of songs, although it’s likely that people in modern-day Ireland do not sing much more often than people living in other countries.

If you want to listen to Brian Boru’s March as plaid on the harp, just click here.