By

Everybody who has travelled to Greece once was in all likelihood amazed at how proud the Greeks are about their past. A taxi drive, for example, informs the traveler that it was one of his ancestors that had invented the alphabet, and a landlord elaborates on how the Greeks had saved the Western world from the Persians. With more conviction than factual knowledge about history, anyone waxes lyrical about the past to deliberately deceive oneself that the glorious times when Greece was the point of origin of culture, are long gone.

Likewise on the new euro coins, Greece refers to his past with several subjects. The 1 cent piece depicts a trireme, i.e. that type of ship the Athenians owed their rise to a major power to; that type of ship which the Greeks used to defend their country against the attack of the Persians.

Herm of Themistocles. Source: Wikicommons.

The year is 480 B. C. The 300 ships of the Greek fleet lay near Salamis in the Saronic Gulf, incapable of saving the city of Athens from being destroyed by the approaching Persians. It is night, and there is a heavy quarrel going on at the ship of the Spartan naval commander Eurybiades. The general as well as most of the inhabitants of the Peloponnese would like to pull back the fleet in order to contain the Persians a little further in the South, at the new wall near the Isthmus of Corinth. But the Athenians under the command of Themistocles reject these plans. They have a major say in these matter because the city of Athens, with its 200 ships, provide the fleet’s lion share. But apparently the Spartan general doesn’t allow himself to be convinced. The Athenians leave the ship, disappointed. It seems that the Greek mainland and Athens with it is lost. Themistocles, however, isn’t a man to give up that easily. He devises a plan. A small rowing boat leaves the trireme that is commanded by Themistocles on the quiet. Inside sits a slave with meticulous instructions as to what he ought to tell the Persian King of Kings. And while Themistocles waited, he might have reflected upon how it could have become possible that the Persians were about to destroy his beloved home town and now threatened the entire Greek civilization.

Map of the military operations during the Ionian Revolt which will lead to the Greco-Persian Wars. Source: Eric Gaba / MinisterForBadTimes / http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

It all had started not in Greece but in Asia Minor where Croesus, King of the Lydians, was ambitious to expand his dominion. He invaded the Persian Empire, was defeated and lost his own country. That made several Greek cities that used to pay tribute to Croesus become subject to the rule of the Persians. For nearly 50 years, everybody was content, until disturbances arose. Herodotus records why the Greeks suddenly couldn’t stand the Persian control anymore: Aristagoras, the leader of Miletus, had made a fool of himself in a military operation and was afraid of rendering an account to the King of Kings. That was why he was said to have established a democracy in Miletus whose popular assembly did what he hoped for: in 500 B. C., they cut themselves off from the Persians.

Other cities joined in and all of a sudden the whole of Asia Minor was in rage. The cities in the mainland were asked for help. But only Athens and Eretria promised to provide support – albeit not free from selfish motives but because Athens, depending on the supplied of grain from the Black Sea region, feared for the safety of its trading routes. It withdrew its help as early as 498 B. C. As a result, the Athenian ships were spared the crushing by the Persian fleet. Miletus was razed, its citizens were sent to exile to Mesopotamia.

It took some time for the mainland to notice the repercussions of the Ionian revolt. But in 491 B. C., representatives of the King of Kings showed up ordering the Greeks to submit. Athens and Sparta refused to comply but many other Greek cities, particularly those in the north, allowed the Persians to intimidate them. They supported the Persians upon their army landing near Marathon in September 490 B. C. to make Athens see reason. The army wasn’t big, though. To the Persians, that campaign was minor border warfare of no essential importance. On the other hand, it was important enough to become a threat to Athens, especially as it turned out that the other Greek cities wouldn’t be much of a help.

Only Plataea sent 1,000 men to assist the 10.000 hoplites from Athens. And then the incredibly happened: the phalanx of Athens had the edge over the Persian army. The Athenians proved victorious and as of then could boast of themselves as spearhead of Greece against the barbarians. This is the context which the (unhistorical) marathon runner belongs to that is said to have informed the city of Athens about the victory.

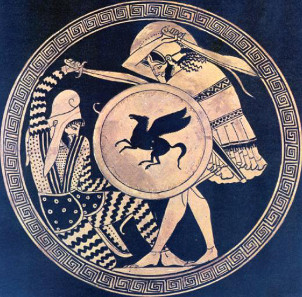

Greek hoplite and Persian warrior fighting each other. Attic red-figure kylix, 5th cent. B. C. Photograph: Wikicommons.

From that moment on, the politicians in Athens were constantly aware that the Persians would take revenge at some point in the future; and they would come not just with a small army, but as a massive invasion. Indeed, Xerxes systematically planned this campaign against the Greeks. A channel was dug through the island of Chalkidiki for the fleet; troops in the entire empire were concentrated. Of course, the Greeks got wind of that. In the popular assembly, Themistocles moved for the surplus of the rent of the Laurion mines to be spent on the construction of a fleet.

Apart from that, a conference of all the Greek states that had no intention to bow to the Persians was initiated. By far, that included not every city. Many entertained good relations with the Persian King of Kings and supported him. After all, Persian dominion didn’t mean that a city was deprived of its self-administration. It was just about paying reasonable tribute and sending soldiers. As a general rule, the wars the Greeks cities fought against each other witnesses much more cruel repercussions. Be that as it may, in autumn 481 B. C., roughly 30 Greek cities stroke a league against the Persians. Today, that is often referred to as the first sign of a Greek community spirit.

First, the Greeks tried to block the pass of Tempe at the northern frontier of Thessaly. That position, however, was difficult to hold and so the forces pulled back to the front gate to central Greece, the Thermopylae. The story of Leonidas and his 300 men is common knowledge. The Greeks intended to hinder the Persian army from marching to give its fleet enough time to gain a decisive victory. But the operation failed, and Leonidas could only cover the retreat of the Greeks. 300 Spartiates, 700 Thespians and 400 Thebans lost their life in the course of events. The Persian King of Kings was deeply impressed by that. He knew then that there were Greeks willing to fight for the freedom of their native country to the last breath.

But he went on sailing. His next target, that much was clear, was Athens. So the Athenians decided to remove all non-combattants, i.e. the women, children and the elderly, to a safe place, to Troizen, Aegina and Salamis. All men fit to bear arms were ordered to go on board the battle ships to defend their home. Athens fell into the hands of the Persians. They destroyed the city.

Fleet of triremes made up of photographs of the modern full-sized replica Olympias. Source: Wikicommons.

And that takes us right back to Themistocles who is still sitting on his ship, waiting for a slave to bring him an answer. He watches the sea. Everything is calm. But suddenly, in the far distance, he spots something. Yes, he did it. The Persian fleet blocks the Greek ships’ escape route. You see, that was the message he wanted to send the Persian King of Kings: this was the ideal place for fighting a battle. The Greeks, however, were about to leave their position; that was why Xerxes rather had to hurry when he wanted to confront the fleet.

Thus, the huge fleet of Xerxes faced 300 Greek triremes in the morning. The crew was tired for the men had rowed the entire previous night to reach their new position. The Greeks, on the other hand, felt fresh and were eager to peak. And that was of the essence. In the 5th century, naval tactics were all about hitting the other ship in the flank with the ram bow located at the prow of one’s own ship. Speed of action was vital and that was something that could only be achieved when all rowers worked together perfectly. And how the Greeks had practiced! The battle took 12 hours, and finally, towards the evening, Xerxes gave up. Admittedly, he tried to take Greece after all, with the aid of his army on land, but that plan likewise failed, near Plataea. Led by Spartan Pausanias, the army of the Greek city-states defeated the Persian forces. Greece, no Athens, Sparta, Corinth and their confederates had successfully defended their freedom.

The acropolis of Athens – symbol of power and wealth. Photograph: A. Savin / http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

What happened in the aftermath of these events? Well, it doesn’t take long to tell. The Athenians made use of their military supremacy to take the place of the Persians. In 478/7, they founded the Delian League. Many cities who felt threatened by the Persians, joined in. Athens promised to organize the defense against the Persians. Wealthy cities were expected to support the Athenian fleet with ships while other cities contributed with payments. The expenses were fixed at the amount of 60 talents and allocated to the members. At first, the treasury was kept at the island of Delos, and Athens actually won the freedom for the Greek cities. Soon, however, Athens interfered in the politics of their confederates and forced them to remain in the Delian League. Wars were fought to preserve the dominating position of Athens.

In 454, the treasury was moved to Athens where the Athenians had it at their disposal. This way, the members of the Delian League for the allowances an Athenian was entitled to when visiting the jury trial. They paid for the rebuilding of the acropolis and the cult statue of Athena. They paid for the sacrificial animals on the occasion of the Panathenaea. They paid and paid. The cultural upturn of Athens in the Periclean era was financed by the oppression of the members of the Delian League. The Athenian trireme – at Salamis, symbol of Greek freedom – had turned into a symbol of oppression by Athens.

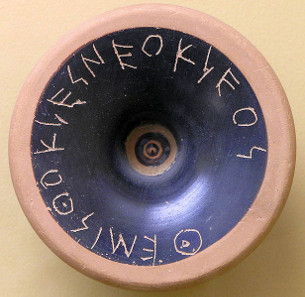

Piece of pottery from the ostracism of Themistocles. Photograph: Marsyas / http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/deed.en

What about Themistocles? Roughly ten years after his victory near Salamis, he was ostracized and had to flee from Athens. He sought refuge at the Persian King of Kings who entrusted him with the city of Magnesia out of thanks for the information Themistocles had provided him with at Salamis. The sons of Themistocles still lived peaceful and content under the rule of the Persian Great King who had proven to be more thankful and just than the dear fellow-citizens at Athens.