In March 1788, a police unit of the Westminster community stormed a locked room in London. They had been tipped off that two people committed a crime in that house that was forbidden under penalty of death: false coining. The policemen, under the command of Edward Treadway, apprehended two persons red-handed: 19 year-old Christian Murphy and his accomplice Catherine Heyland.

Sixpences from 1708, 1731 and 1787 – most probably it was coins like these that were counterfeited by Christian Murphy and his accomplice Catherine Heyland. Source: Baldwin’s Auctions, London 52 (2007).

In the counterfeiters’ workshop

The civil servants collected carefully every piece of evidence they could find in the room. On the windowsill, for example, a saucer with wet sand stood. A handful of old sixpences lied on top and two fresh counterfeits next to it. During the search the following things turned up as well: a file, a bit of sandpaper, a cork, some “black stuff” and a pair of tweezers. Even more suspicious were a melting pot and, well hidden between ceiling and the roof in front of the window, an “iron flask”. On the mantelpiece a phial with “Aqua fortis” (nitric acid”) stood, plus a vessel for pouring the metal in the mould, a scale and white arsenic. The civil servants identified all that as classic equipment of a counterfeiters’ workshop. The last piece of evidence was provided still during the search: a man brought suspect Christian Murphy a couple of shirts – in one of these shirts counterfeited money was found. During a carful body search the police seized two further pouches with counterfeit money. They had found it in Catherine’s bodice.

Court room in Old Bailey, photograph from 1895.

In court

Thanks to the report of the proceedings we have a detailed explanation as to what purpose our forgers used the different tools that were found during the search. John Nicholls, then director of the Royal Mint in the Tower, appeared in person in court in Old Bailey in April 1788 to enlighten the judge and the jury on that. He explained that the iron flask the two suspects had hidden so carefully outside the room, was a die with which to make an impression of both sides of a coin in the sand-filled vessel. The first impression was made with coarse sand, which was smoothed with finer sand to avoid “small, irregular holes in the cast work piece”. Afterwards, the sand mould dried above a fire. Subsequently, the metal for the cast had to be melted. By adding arsenic, the copper appear a shade lighter and hence similar to silver. John Nicholls called this mixture “East Indian copper”. The nitric acid had a similar effect after the cast. If there was any trace of silver in the mixture it would appear at the surface at the counterfeit when doused into nitric acid. After the sixpence piece cooled down it was worked on with file, sandpaper and cork. In summary, John Nicholls explained to the High Court, Christian Murphy und Catherine Heyland had “full equipment for false coining” in their possession and surely made use of it.

Although the young counterfeiter gallantly rallied to his companion and did everything he could to clear her of blame the court didn’t believe him. Both were sentenced to death due to false coining. But what did that mean in those times? Christian Murphy had to expect the gallows. His female companion surely didn’t get off that cheaply. For her, it would be the stake and being burnt alive.

The burning of Ann Beddingfield in 1763; the court had showed her the mercy to be strangled before the burning.

Three executions

It wasn‘t that that back then, one year prior to the French Revolution, nobody had considered if that was legal. That simply was how it was. And not really seldom, by the way. You see, in April 1788 our two defendants were the only ones sentenced due to false coining. Another couple, Jeremiah Grace und Margaret Sullivan, had confessed in court in the same month and, together with our protagonists, waited on Monday, June 23, 1788, in the court room to be informed about the date their execution would be carried out. The two men were to be hanged on Wednesday, Margaret Sullivan to be burned that very day. Catherine wasn’t to die with the other three. She had a high-ranking civil servant convinced that either she wasn’t guilty or at least not so guilty that she deserved such a savage penalty. Sheriff Bloxham, a very decent and dedicated man, was to come through for his protégée again and again. In this session, on June 23, 1788, he successfully got the court to suspend Catherine’s punishment at least for a month. Bloxham hoped that common opinion would speak up for the young lady. And indeed, the Times wrote the following on June 24, 1788: “Must not mankind laugh at our long speeches against African slavery (…) when (…) we roast a female fellow creature alive, for putting a pennyworth of quicksilver on a half-penny worth of brass.”

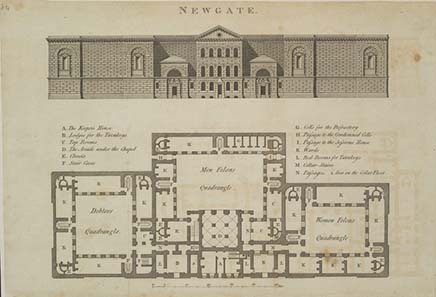

And the day came, June 25, the date Christian Murphy, Jeremiah Grace und Margaret Sullivan were due to die. Already in the early morning, the curious onlookers crowded in front of the Newgate Prison where all executions took place since 1783. The audience watched the unpleasant building made of coarse stones that had been built only six years ago. There the prisoners were kept, in front of its walls they would die – not a very enjoyable prospect. In the 18th century, hope was invested in the deterrent effect – a public execution acted as deterrent, all right, even though such an “event” was an amusement for the people rather than a moral correction.

In the meantime, the viewers fought about the best places to stand and watch. Young men climbed on the balconies of the surrounding houses. The pubs in the vicinity made record sales and small souvenir gallows became bestsellers.

At seven 7 a.m. sharp, William James and Jeremiah Grace were fetched from the prison. The carried black hoods on their heads, their hands were tied on their backs. The hangman put the noose around their necks while the crowd shouted “Get off the hoods!” – by that the people didn’t mean to take off the cap to show reverence in the face of death; no, the shouts were directed towards the black hoods which mercifully concealed the final facial convulsions of the condemned criminals. The preacher gave a short sermon, then, at 8 a.m. the trapdoor underneath the feet of the delinquents opened and the counterfeiters dangled in the air.

Afterwards, Margaret was presented, wearing a white penitential robe. A stake had been erected for her, in whose center she ascended a stool. Solemnly the sheriff’s men lit up the stake – Margaret burnt to death.

Moral scruples

While the mob, most probably drunk by then, watched the spectacle with excitement, the higher social strata were appalled by the hideous smell of a burning corpse. After all, one was humane, and hence The Times raised a cheer about this statement from the following day stressing that the country had been so proud about punishing offenders without the slightest cruelty: “Is the burning a woman no torture? The very savages in the wildest parts of the world, pay respect to their females, while Great Britain selects their tender bodies as the only objects for excruciating torture.”

Between life and death

While lively discussions about the gender gap were going on at the tea tables of the Empire, Catherine awaited her execution in prison. Her benefactors were on summer holidays and recreated. It seemed that Catherine’s fate was forgotten. Nothing happened and so the end of deferral was imminent which meant that the execution was due on July 21. But there was still Sheriff Bloxham. When he realized that there wasn’t going to be a second deferral, he got on his horse and rode at a full gallop to the country house of the Home Secretary. He arrived there at three in the morning, demanded that the perplex servant would lead him to his Lordship immediately. The servant complied, and one hour later Sheriff Bloxham left, holding the redeeming paper in his hand.

In the meantime, the stake had already been built in London. Like the prior month, the sanguinary crowd had gathered to watch the counterfeiter burn. Their fray most probably was so loud that Catherine was able to hear it in prison where she prepared herself for her unpleasant death, accompanied by a priest. Two hours before the execution, Sheriff Bloxham reached Newgate. He stormed the prison and got Catherine Heyland another four days. The stake was dismantled for the time being, the wood took away, only to be carried there again on Wednesday for the next stake. Finally the message arrived that suspended Catherine’s execution and hence placed it on hold indefinitely.

Map of New Gate Prison, built in 1782. Source: Wikipedia.

Captured!

The name of the counterfeiter was on the death list for almost a year, the woman waited for the date of her execution to be fixed or a reprieve for almost a year. She did that under horrible conditions. The prison cells of Newgate were arranged around three courts. Those possessing the financial means could arrange for a relatively comfortable accommodation when they paid for a private cell and got themselves food from outside. Catherine was poor. She didn’t have that option. She lived there together with 151 other female inmates in the three women’s cells in December 1788, which were meant for 70 inmates only. A window brought air to the overcrowded dormitory. There were no beds, only a ledge at one end of the room with wooden beams attached to it which served as mattress and pillow. For the privilege of sleeping there, money had to be paid weekly. A blanket made of coarse hamp cost an addition fee. Those who couldn’t afford that, had to coil themselves up on the ground that was moist (what of is an issue one rather doesn’t think about). It was said that the cells were so terribly smelly that the prison warders, when opening the doors in the morning, drank a glass of spirit to avoid passing out because “the penetrating smell and the blight” took even the most hardboiled men’s breath away. Most probably Catherine wasn’t well fed. The food ration was for the calculated 70 persons – now, all the women present had to share them. They were troubled with the incommodiousness, hunger, dirt, and, if that wasn’t enough, the fever. Additional women were thrown in the dungeons every day. Catherine lived between them all for more than a year until a little miracle happened.

George III wearing the coronation robe – an image taken in better days. It was his illness and, most of all, his recovery, Catherine owed her reprieve to. Source: Wikipedia.

The rescue

In autumn 1788, George III had become seriously ill. He suffered from a mental disease that made it impossible for him to conduct government affairs. Rumour had it that the king had shaken the branch of a tree for he believed it was the King of Prussia, and things like that. The king’s illness resulted in a serious government crisis because the members of Parliament agreed on a regent – the Prince of Wales and official successor of the king – but not if he was entitled to hold the title of a prince regent or the government had the right to proclaim him. Government affairs were delayed when the king recovered – nobody expected that happening so soon. In April 1789 it was celebrated that George III had been officially declared sane and able to govern. Great festivities were conducted throughout the country of which the poor got their share, too. And Catherine Heyland was reprieved, together with another 15 women. Their fate wasn’t to be executed but to be deported to spend a lifetime in Australia. How such a passsage to “Down Under” was like back then and what fate the ladies awaited in the new world can be read in the book of Siân Ree “The Floating Brothel: The Extraordinary True Story of an 18th-Century Ship and Its Cargo of Female Convicts“ (Hyperion Books). The author has reconstructed the individual lives of numerous convicted people on the basis of archival sources – our example, the case of the counterfeiter Catherine Heyland, is likewise taken from her interesting, well written and sometimes a bit distressing book.