courtesy of the MoneyMuseum, Zurich

translated by Teresa Teklic

Why was the human head the motif on coins for centuries, no, for millennia? And why did that change in the last 200 years? Ursula Kampmann is looking for answers to these questions in her book “MenschenGesichter” (“Human faces”), from which the texts in this series are taken.

Italy. 2 euro 2002. Nominal value, in the background map of Europe. R. Bust of Dante with laurel wreath, facing left. © MoneyMuseum, Zurich.

At the end of the 2nd millennium, 15 European states were faced with one question: What motif should they pick to represent their nation on the euro coin? Which image could function as a unifying symbol that millions of citizens of the respective country would be able to identify with? How did the countries want to present themselves to their neighbouring states, where the coins would be in circulation as well?

Each nation found its own solution, determined by tradition, history, and form of government. In some cases the images were chosen by officials, in others by commissions. In Italy it was the people who voted for the images that would decorate the future euro coins during a TV show on RAI Uno, which had an incredible viewing rate. The motif that the people finally chose for the largest circulation coin was Dante Alighieri.

It may be strangely moving that a nation so extremely rich in historical personalities does not portray a Roman emperor, Pope, or politician, but a poet on its coins. The Italians do, nevertheless, pay tribute to the man who first turned Italy into a nation – on a cultural scale, if not on a political one.

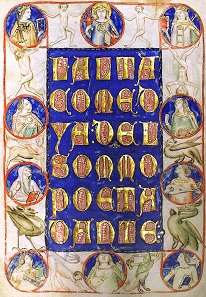

LALTA COMEDYA DEL SOMMO POETA DANTE, title of the Codex Altonensis; manuscript with illuminations, Northern Italy, around 1360. Source: Wikicommons.

Before Dante’s “Divine Comedy”, Latin was the language of the educated people, while the common folks in the streets conversed in local dialects. If you travelled, say, from Venice to Naples, you would have had a very hard time understanding the local idioms there.

In the midst of this Babylonian confusion of language, one poet wrote his work in the “volgare”, the language of the streets. And not only of the streets of his hometown Florence, which Dante had to leave at an early age, but in the dialects of all the places that he travelled through while in exile. So Dante’s “volgare” was an artificial and artful language, which, due to the popularity of his work, became the new language of the educated. Thanks to Dante, merchants from Padua were suddenly able to converse with clergymen from Rome, the Florentine dyers could communicate with their colleagues from Prato, and the commands given by captains from Genoa were understood by the sailors from Bari. Being Italian was re-defined as speaking Dante’s language and knowing the contents of his Divine Comedy.

Even today, Italy remains a nation of culture more than a political body, in which its inhabitants consider themselves responsible citizens of a country. And that is exactly why Dante, as an embodiment of what is essentially Italian, is the best motif imaginable.

You can find all episodes in the series here.

A German edition of the book “MenschenGesichter” is available in print and as ebook on the site of the Conzett Verlag.