courtesy of the MoneyMuseum, Zurich

translated by Teresa Teklic

Why was the human head the motif on coins for centuries, no, for millennia? And why did that change in the last 200 years? Ursula Kampmann is looking for answers to these questions in her book “MenschenGesichter” (“Human faces”), from which the texts in this series are taken.

Swiss Confederacy. 100 francs 1925, Bern. Bust of a woman in traditional rural garb facing left, against a mountainous landscape. R. Swiss cross surrounded by aureola above nominal value and year of issue, below Alpine rose branch. © MoneyMuseum, Zurich.

At the end of the 19th century, the Confederacy’s financial department decided to commission a new coin motif that would render “Helvetia accessible to a broad Swiss audience by relying on a Swiss, national motif, an allegorical or historical-symbolic representation of her” (in translation).

When the jury came together in May 1895 in order to discuss the 21 designs that had been handed in, they were unable to pick one design that fully realised all their expectations. The proposal that came closest to what the venerable members of the jury had imagined was the work of Neuenburg medallist Fritz Landry, who had modelled Helvetia as a young, pretty maiden. If he could only make her look a little more mature and maternal, the experts thought, the maiden might finally turn into a true Helvetia.

Landry got to work. He took his model’s open hair and tamed it by putting a neat braid around it. The facial features became a little bit rounder and a wreath of edelweiss around the neck replaced the rhododendron. One could almost have grown to like this version, if it had not been for a concerned magistrate, who remarked that the stray curl on her forehead gave “the wench a frivolous look”. And this was, quite obviously, absolutely not befitting for a figure representing the dignity of Switzerland.

So the curl disappeared and the new “Vreneli” was finally on its way. Do not believe, however, that the experts on this topic were happy about such a beautiful new coin motif. On the contrary, it was criticised that the homeland was, in fact, a maternal and nurturing figure. Hence it should only be represented by a mother in the years between her youth and ripe age. Also, one was of the opinion that the coin would only reinforce a prejudice widespread among tourists that Switzerland was a country made up of mountains and the Swiss people a nation solely made up of shepherds and hoteliers.

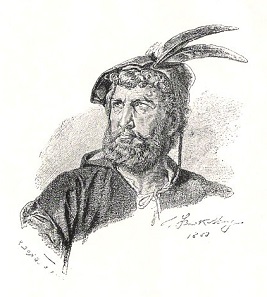

Ernst Stückelberg, William Tell. Illustration, 1880. Some critics would have liked to see William Tell on the new coins rather than the Vreneli. Source: Wikicommons.

The Schweizer Numismatischen Rundschau (“Swiss Numismatic Review”) wrote at the time (in translation): “Our country would have been better represented by William Tell or the Three Tells.” And this is what actually happened in 1955. The golden 50-franc pieces with the Three Tells, or oath takers, and the 25-franc pieces featuring William Tell, also made of gold, were kept in the National Bank’s vault until a mandarin of the Swiss National Bank decided to have them melted down.

Nevertheless, whatever the experts said, the Swiss loved their “Vreneli”, as the lady on the 10-, 20-, and 50-franc pieces has affectionately been called since World War II.

The next episode will centre on the freedom fighters of the Spanish colonies in South America and it will tell you how Bolivia got its name.

You can find all episodes in the series here.

A German edition of the book “MenschenGesichter” is available in print and as ebook on the site of the Conzett Verlag.