courtesy of the MoneyMuseum, Zurich

translated by Teresa Teklic

Why was the human head the motif on coins for centuries, no, for millennia? And why did that change in the last 200 years? Ursula Kampmann is looking for answers to these questions in her book “Menschengesichter” (“Human faces”), from which the texts in this series are taken.

Julius II, real name Giuliano della Rovere, Pope (1503-1513). Giulio, Rome. Bust portrait of the Pope to the right. Rv. Saint Peter with keys and book in frontal view, below the keys, trident as symbol for the Fugger family in Augsburg, who managed the papal mint. © MoneyMuseum, Zurich.

“Il ponte terribile” is what his contemporaries called Giuliano della Rovere, who took office in 1503 as Julius II. His short period of office only lasted ten years, but as a tourist in Rome you will find traces of this influential historical figure everywhere.

“Out with the Barbarians,” was one of the Pope’s maxims, a Pope who was just as adept at handling a sword as he was at handling his ferula. He personally led the campaigns which won back the cities Bologna and Perugia for the Papal States and expelled the French king from the country.

Raphael, portrait of Pope Julius II, 1511-1512. Source: Wikicommons.

But offensive warfare was costly. And so were the many artists employed by Julius and paid with money from the papal treasury. Michelangelo created the frescos in the Sistine Chapel, his Moses and the Pièta, Raphael painted and Bramante began rebuilding the St Peter’s Basilica in 1506, a project that the Pope couldn’t really afford. So he sought new ways of generating income and found them in the sale of indulgences.

Originally, this special way of confessing followed a straightforward logic: in exchange for repentance and a good deed the sinner could expect divine forgiveness. This deed could for instance be a donation, made towards a project of the Church, such as the construction of the St Peter’s Basilica.

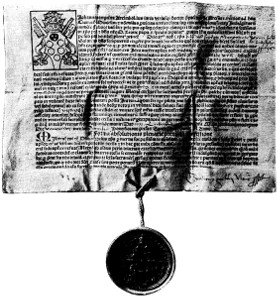

Letter of indulgence, issued in the name of Leo X, 1515. Source: Wikicommons.

Over the years, however, this simple financial transaction had been somewhat complicated. After all, the Pope needed the money immediately, which is why he took it out from a bank first. In exchange, he transferred the right to sell indulgences to the bank, which it did professionally and according to the latest insights into finance management. Only a set percentage of the revenue went to the Vatican. It was still a large enough sum that the Fugger trading company, which was managing the sale of indulgences in the Holy Roman Empire, had been able to set up a branch in Rome as early as 1495. The Fugger family ran their business so successfully and efficiently that Julius II even leased the Roman Mint to them in 1510.

The coins from that time – just like our coin here – exhibit the Fugger trademark, a trident. So not only does this coin bear witness to the great Pope Julius II, it is also a symbol of the increasing interconnectedness of economy, religion and politics that was so typical of the Renaissance and so fiercely criticised in Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses.

In the Early Modern Period, powerful women were everything but common and even less commonly were they eternalised on coins. One exception is Isabella I of Castile. Our next episode is all about her.

You can find all episodes in the series here.

A German edition of the book “Menschengesichter” is available in print and as ebook on the site of the Conzett Verlag.