courtesy of the MoneyMuseum, Zurich

translated by Teresa Teklic

Why was the human head the motif on coins for centuries, no, for millennia? And why did that change in the last 200 years? Ursula Kampmann is looking for answers to these questions in her book “Menschengesichter” (“Human faces”), from which the texts in this series are taken.

Milan. Galeazzo Maria Sforza (1466-1476). Ducat. Armour-clad bust of Galeazzo to the right, above, frontal view of the bust of Saint Ambrose of Milan. Rv. Visconti coat of arms, above, crest, in the left square, staff with two buckets. © MoneyMuseum, Zurich.

Galeazzo Maria Sforza’s great-grandfather was a peasant, when his 12-year old son decided to become a mercenary.

At the time, Italy resembled one great battlefield. City states were continuously at war with one another. These cities were populated by citizens, whose crafts and trades afforded them a comfortable life and who were anything but willing to risk their lives in war. And why should they? Italy had seen the emergence of a thriving service industry specialised on such needs. Fully equipped soldiers, complete with their commanding officers, were available for rent. The contractors of war were named condotierri after the “condotta”, the contract of lease. They invested their own capital in the recruitment of soldiers, provided the soldiers’ food and pay and made a decent profit hiring them out to clients. The grandfather of the future Duke of Milan joined the army of such a condotierre.

This young man, soon nicknamed “Sforza” (ital. proud, defiant), had a natural talent for warfare. He started from scratch and less than 30 years later commanded his own mercenary army.

Like all condotierri, the first of the Sforza also dreamed of climbing the social ladder. Upward social mobility in Italy had never been greater than in the 14th century. Among the condotierri were impoverished aristocrats, run-away monks, sons of craftsmen and peasants. And every single one of them was theoretically able to acquire his own army, if he was entrusted with one by his employer or, even better, if given the chance to marry a wealthy heiress.

Bonifacio Bembo, Portrait of Maria Visconti, around 1460. Source: Wikicommons.

And that’s exactly what Francesco, the son of our first Sforza, did. As it happened, the last Visconti, the Duke of Milan, was out of money and therefore gave the by then very powerful condottiere his only, though illegitimate, daughter in exchange for military support.

In terms of strategic marriages, this was as good as it gets. His marriage provided Francesco with the necessary legal ground to conquer Milan after his father-in-law’s death. By 1450, Milan’s citizens were devoted to him and by 1454, he was also recognised by the other Italian rulers.

Bonifacio Bembo, portrait of Francesco Sforza, around 1460. Sforza insisted on being painted with the old hat he used to wear as a condottiere. Source: Wikicommons.

Francesco Sforza became a respected signore and admired by contemporaries as the “arbitrator of Italy”.

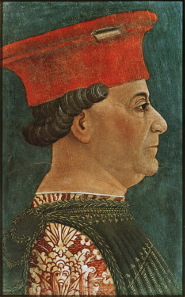

Piero del Pollaiuolo, portrait of Galeazzo Maria Sforza, around 1471. Source: Wikicommons.

Building on this legacy, his son Galeazzo Maria Sforza, minting authority of our coin and grand-grandson of a peasant and a Duke, inherited his father’s office without meeting with the slightest resistance.

Stay with us for the continuation of the Sforza family history. The next episode will focus on the assassination of Galeazzo Maria Sforza and the fight over his succession.

You can find all episodes in the series here.

A German edition of the book “Menschengesichter” is available in print and as ebook on the site of the Conzett Verlag.