courtesy of the MoneyMuseum, Zurich

translated by Teresa Teklic

Why was the human head the motif on coins for centuries, no, for millennia? And why did that change in the last 200 years? Ursula Kampmann is looking for answers to these questions in her book “Menschengesichter” (“Human faces”), from which the texts in this series are taken.

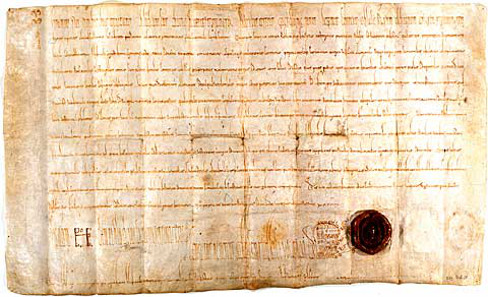

The document by which Louis the German founded the Fraumünster in Zurich for his daughter Hildegard on July 21, 853. Source: Wikicommons.

In 853, Louis the German founded a new convent in Zurich, which would be presided by his daughter Hildegard. The foundation of convents was a common practice at the time to ensure unmarried women from ruling families could lead a life befitting their social status and at the same time, to exert influence over strategically important territories through a member of the family. Of course Hildegard did not inspect her estates on horseback herself and of course she did not lead her army in person. For that she had her ministeriales. On the other hand, she was the only person they would take orders from. And so Hildegard, and after her many abbesses, ruled over a territory that was among the most influential in the Holy Roman Empire.

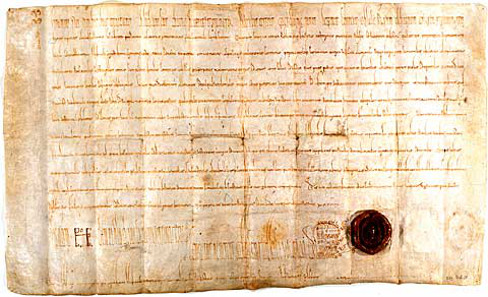

Fraumünster Abbey, Zurich. Beginning of the 14th century. Inscription “ZVRICH”, frontal view of the head of the abbess of the Fraumünster with hood.© MoneyMuseum, Zurich.

It was impossible to ignore a woman as powerful as the abbess. The German Emperor, who possessed the right to institute her, relied on her loyalty. Henry III for instance, who was also Duke of Swabia and in this office a common visitor in Zurich, recognised the abbess as important ally and made her the ruler of Zurich by investing her with the rights to levy customs, hold market and mint coins.

But already under his son, Henry IV, the imperial privilege of investiture became an issue of debate and by the end of the 12th century the convent was electing its abbesses independently. This development only made it even more important for the Emperor to secure the loyalty of this powerful woman by granting her special privileges. Frederick II for instance, who stopped in Zurich on his way from Italy to Germany, bought the convent’s support by granting it imperial immediacy: this meant that from the year 1218 onwards, no one but the Emperor himself was to give orders to the abbess.

So the abbess occupied one of the Empire’s most influential positions and proudly presented herself as such – as the abbess of the Fraumünster – on her coins since the early 14th century. Which abbess exactly ordered the minting of the coin depicted above, we’ll never know. Once more, the individual disappears behind its position. Once more, it is not the person which counts, but the office she occupies and the power she holds. Interestingly, this particular self-representation of the abbess emerges just at that point in time when the power of her real model was already on the wane.

In the next episode, you’ll learn how the relics of Saint Stephan of Halberstadt saved a diocese from its closure.

You can find all episodes in the series here.

A German edition of the book “Menschengesichter” is available in print and as ebook on the site of the Conzett Verlag.