by courtesy of Jürg Conzett, MoneyMuseum

Money and Currencies in history

Part III: Modern Times

Numismatics is down to specialists only! Most scholars, most coin collectors adore their tiny little subject and do not know anything about neighboring fields. But sometimes you want to have an outline of all the most important currencies that have been used. The Zurich MoneyMuseum has issued a popular booklet on this theme a few years ago. In the meantime the revised edition is ready to be published. We will present its text in CoinsWeekly by courtesy of Dr. Jürg Conzett.

Spanish Peso

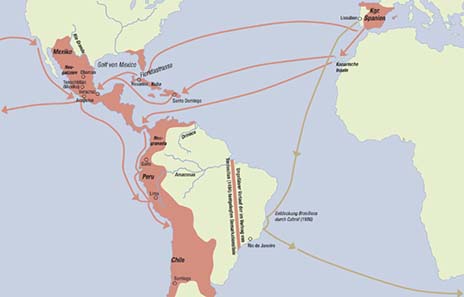

The Spanish Spoliation of America in the 16th Century

During the first half of the 16th century, a series of happy coincidences converted Spain into the richest and most powerful country on earth at the time. In 1519, Hernán Cortés conquered the huge Aztec Empire with an army of only 600 soldiers; in 1531, Francisco Pizarro succeeded in destroying the Inca Empire with 180 mercenaries.

Not the booties, however, but rather the enormous deposits of silver at Potosí and Zacatecas produced the true wealth of Spain. They allowed for incredible masses of silver to be won by the latest methods. In the thirties of the 16th century, “only” 86 tons of silver reached Spain, whereas in the seventies, silver production increased to 1.119 tons and stagnated at around 2.200 tons per decade during the first third of the 17th century.

Two great dangers threatened this wealth. On the one hand, storms and heavy see claimed their tribute: 402 ships fell victim to adverse conditions between 1546 and 1650. Bearing in mind that one ship could transport up to 300.000 reales de a ocho, it is easy to see why even today private entrepreneurs go on expeditions to salvage those wrecks. On the other hand, England, France and the Netherlands, which were at war with Spain, supplied corsairs with letters of marque in order to capture Spanish galleons. English pirates, among them the well-known Francis Drake, were temporarily able to snatch up to 15 % of the silver with destination Seville. Nevertheless, the major part of the silver reached its destination, and this meant an enormous increase in power for the Spanish king because he collected the lion’s share of this flood of silver by means of taxes and duties. But neither Philip II (1556–1598) nor his successors succeeded in investing this capital wisely in the improvement of the infrastructure. The silver from the New World paid Old Europe’s wars of religion instead. This overcharged even America’s stock of precious metal, even though it had appeared to be almost inexhaustible: Philip II had to declare national bankruptcy several times.

Spanish mentality, which considered all trade and industry degrading for a noble man, brought it about that the silver did not remain in Spain, but flowed off to other European countries. The Venetian ambassador noted clear-sightedly in 1595, “The Spaniards state with quite good reason that the treasure which comes from the West Indies to Spain produces the same effect as rain on the roofs. If there is heavy rain, the water will pour down and the first to be hit won’t be able to profit.”

So the silver was for the benefit of the whole of Europe – and it came just in time. During the Renaissance, trade had enormously increased and the constant lack of silver handicapped business. At last, enough precious metal reached Europe to strike as many coins as needed. The reales de a ocho, earned by selling arms and by soldiers’ pay, were melted and converted into the various national currencies. Spanish silver financed German, Italian, English and Dutch economic growth.

Spain, Philip II, King of Spain 1556-1598, real de a ocho, silver, Segovia, 1580

The most important silver coin, the real de a ocho, was invented not in Spain, but in the New World. The viceroyalty of New Spain authorized the mint of Mexico-City by a note written in 1537 to strike coins valued at 8, 4, 2, 1 and 1/2 reales. Due to technical difficulties, the mint did not strike the new high nominal immediately. But around 1560, it spread over the whole Spanish Empire.

Our coin was produced in Segovia in 1580, which is clearly indicated by the mintmark, an aqueduct. Philip had built a mint disposing of the latest technology there with the help of his Austrian relatives. It was equipped with a rolling mill, a new Austrian invention, which made it possible to strike much better coins than with the hammer.

Spain, Philip V, king of Spain 1700-1746, real de a ocho, silver, Mexico City, 1738

In Germany, they are called “Schiffspesos”: the coins that came to Spain from the New World. Pesos because this term refers to coins of the weight (span. peso) of eight reales, and ship because in the 17th century, the crude coins were believed to have been struck in the course of the passage in order to avoid the tax that was charged when silver bars were imported. Coins paid no toll.

The reverse presents the Pillars of Hercules, which were considered to be the bounds of the habitable world, and a banner featuring the motto PLVS VLTRA (lat. for beyond that). They became a symbol of the New World – the dollar sign is believed to originate from the two pillars and the banner winding around them.

Spanish reales were the most important trading coins in the Far East. Enormous bulks of silver were shipped to India and China to pay for luxury goods such as silk, tea or spices. In India, the silver coins were re-minted as rupees at once, whereas the Chinese used the foreign coins in their own monetary transactions.

The negative balance of trade between East and West did not change until the English discovered opium. Soon a profitable triangular trade between England, India and China developed, making the use of pesos unnecessary: Cheap cotton goods were shipped from England to India and traded for opium, which in turn was sent to China to barter for luxury goods for England.

The Struggle for the New Worlds

The discovery of new trade routes excited the greed of other Western nations likewise for resources and products from overseas. While Southern America remained under Spanish control, the Dutch, the British and the French struggled for markets and trading profits in Africa, Northern America and the Far East.

Gold, ivory and slaves were imported from Africa. Northern America supplied fur. The Far East was the favorite destination for 16th and 17th century tradesmen as far as elaborated products of arts and crafts, silk, tea and especially spices were concerned. It was there that the highest profits could be made. Just think, for example, of nutmegs, which grew solely on the Banda Islands. While ten pounds of nutmegs cost less than one English penny on the islands, a merchant paid more than 2 pounds and 10 shillings for the same spice in London – this meant an incredible profit margin of 60.000 – in letters sixty thousand – percent.

No wonder that numerous trading companies sprang up in Europe, hoping to do profitable business overseas, especially in East India. They were privately owned and invested their capital in trading vessels sailing to the Far East. After the return of the merchant fleet, the profit was distributed among the investors. East India companies did not only exist in England; merchants in the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Portugal, France, Austria and Prussia had also founded such promising enterprises.

Private trading companies transacted business with America and Africa, too. Their foundations and trading empires developed into bargaining counters to which the diplomats of the 18th century resorted again and again when they had to make peace once more after one of the various European wars. The Treaty of Utrecht, for example, which brought an end to the War of the Spanish Succession in 1713, won Great Britain Northern America, Newfoundland and the Hudson Bay, in addition to the monopoly of slave-trade in the Spanish colonies of America.

There is little evidence of how the natives coped with the fact that their world was distributed in Europe. The Asians and Africans, the “Indians” and the inhabitants of India, they all had no choice but to yield to the superior military power of the Europeans. Despite their inferiority in number, they held the field in every battle in the long run – thanks to their ships which were equipped with fire-spitting canons and their easily transportable guns.

Along with the European armies, the western monetary system and the profit fixed capitalism gained victory over native currencies and social systems. If today our world is as it is, dominated by western ideas and economic systems, the roots are to be found in the 16th century.

Dutch Guilder

The Dutch Merchants’ Empire

The vicinity to the rough North Sea had made the Dutch excellent seamen sailing the Seven Seas. The United East India Company, which dominated the spice trade in India and Indonesia, was the most important Dutch trading company. It had a monopoly of trade within all territories east of the Cape of Good Hope and supplied half of Europe with spices like cloves, nutmeg and cinnamon. The Dutch West India Company carried out trade with Western Africa and America. New Amsterdam became its best-known colonial settlement, known as New York today.

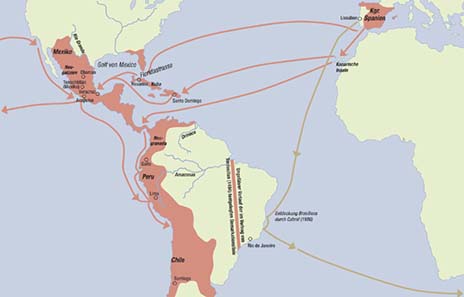

Spanish Netherlands-Flanders, Charles V, emperor of the German Empire 1520-1556, king of Spain 1516-1556, florin karolus without date, gold, Antwerp

Charles V was not only the emperor of the German empire, he also held the office of king of Spain. Thus he controlled the two Sicilies, the Spanish overseas possessions and – probably most important – the rich Netherlands, which paid the greater part of the Spanish inland revenues due to their brisk trading activities and their importance in the textile industry.

In the German empire, Charles created a standardized coin, the Reichsthaler, by conventions in 1524 and 1551. In the Netherlands, on the other hand, he struck the karolus, a silver coin, which was a bit lighter than the thaler. There also existed an equivalent in gold.

Netherlands / West Friesland, 14 guilders, gold (9.93 g), 1751

The Netherlands, which had gained independence from Spain in the so-called Eighty Year’s War of the 16th century, consisted of several independent provinces. Each of them had the right to strike their own coins, as long as they acted according to the common rules. At the beginning of the 17th century, the gouden rijder was introduced, a heavy gold coin valued at 14 guilder. Its name originated from a silver coin named “rijder”, corresponding with the rider on its obverse.

The Austrian Empire

As an Austrian proverb puts it, “Let others wage war, you, fortunate Austria, marry!” This proverb illustrates the fact that in Austria, it was a successful dynastic policy that managed within few generations to create an empire, which had no equal: Maximilian I acquired the rich Netherlands and a part of today’s France by marrying the heiress of Burgundy. His grandson Charles V thereto inherited Spain and the kingdom of Naples from his mother. But soon after the end of his reign, the huge empire was divided again. The German house of Habsburg took over the office of the Roman emperor and ruled Austria and large territories in Eastern Europe. Starting there, merchants traveled primarily to the Levant and Africa. Their coin, the Maria Theresa thaler was to conquer the eastern hemisphere in the 19th century.

Austria, Maria Theresia, archduchess of Austria 1740–1780, thaler, silver (28.0 g), Günzburg 1765

Soon after her accession to the throne, Maria Theresia began to strike thalers. However, the famous Maria Theresa thaler with its constant weight and standard did not come into being until 1753, when Austria and Bavaria agreed on a common trading coin, the Conventionsthaler. Exactly 10 Conventionsthalers should be struck from one Cologne Mark of silver (= 233.856 g). The inscription on the edge, IVSTITIA ET CLEMENTIA (lat. for justice and indulgence), made it impossible to imperceptibly file off silver from the edge and to reduce the value of the coin by that. Hence, the weight and the silver standard of the thaler were guaranteed if the inscription on the edge was intact. This was easy to check – and it made the Maria Theresa Thaler the most popular trading coin of its time.

Austria, Maria Theresia, archduchess of Austria 1740-1780, thaler, silver (27.98 g), Günzburg, after 1780

On our coin, Maria Theresia is not a young woman any more. She is wearing the widow’s veil–her husband died in 1765. Her titles run Maria Theresia Roman empress, queen of Hungary and Bohemia. The reverse mentions further titles like archduchess of Austria. The signature below her neck refers to the coin officials of the mint of Günzburg, one of the most important mints of the Habsburg monarchy.

The thaler traveled over Trieste, the harbor of the Danube monarchy, to Egypt, a center of the coffee trade at the time. The Arabic world sent the silver to China and India to pay for spices and other exotic goods. In return for Austrian silver, Gold and ivory, ostrich-feathers and slaves came from Africa to Europe. In 1780, however, the empress died. Her successor was confronted with the choice of either creating a new trading coin or keeping the Maria Theresa thaler.

Merchants from Augsburg asked Joseph II to continue to strike the thaler with his mother’s portrait. Joseph agreed and decided to use the portrait of the thalers from Günzburg, which he liked best, for all restrikes. Soon they were not only produced there, but also in Vienna, Alba Iulia (Transylvania), Prague, Kremnica, Milan and Venice.

When in the middle of the 19th century the Austrian government decided to suspend the circulation of the Maria Theresa thaler because it did not fit with the currency system any more, emperor Franz Joseph II made sure by means of article 19 of the imperial patent of September 19, 1857 that the thaler could still be struck for the foreign trade. Thus the Austrian mint has produced the Maria Theresa Thaler until today.

The Maria Theresa thaler is mentioned nearly in every travel book from the 19th century, if it was written by someone making a journey to the Ottoman Empire or to North Africa. The locals called the coin Abu Teir (father of the bird, because of the double-headed eagle on the reverse), Abu gnuchtu (father of satisfaction) or simply rial or rial namsawi (Austrian thaler). Its value fluctuated from place to place – just as a reference point, Captain R. A. Mignan, who traveled in Oman in 1820, reported that a date-palm cost 10 Maria Theresa thalers and that such a tree bore fruits valued at one or one and a half thaler per year. In the region of Lake Chad, one of these silver coins was exchanged for 4.000 cowries and in Dshedda, one ounce of fine gold cost 22 thalers in 1810.

When Mussolini planed his invasion of Abyssinia, he needed Maria Theresa thalers because they were the common currency there. Schuschnigg, hoping that Mussolini would support him politically in return, delivered the dies to Rome where huge masses of these coins were struck.

Actually, the Maria Theresa thaler financed the operations of all combatants in the Levant and in Africa during World War II. Between 1936 and 1939, the Austrian coins were struck in London, Bombay, Paris and Brussels; after the war, the mint of Birmingham took on the production. But at that moment, the demand for Maria Theresa thalers was already declining. Saudi Arabia had officially called it in as early as 1928. Abyssinia followed after World War II. Yemen withdrew them in 1960, Oman in 1972.

But even today you will find Maria Theresa thalers in bazaars of the Near East. Jewelers buy them in order to make jewelry.

Franc

Napoleon conquers Europe

When the new French constitution was declared on September 3, 1791, the voice of reason or rather the ideas of the era of Enlightenment had gained a victory. But at the same time, the French had made enemies of every state in Europe ruled by an absolute monarch. In order to stand the ground against superior enemies, revolutionary France created a new military conception: in the militia, soldiers fought from conviction and capable men could rise to the highest ranks. The vanquished were not enslaved, but collected as combatants for the achievements of the French Revolution. Napoleon was to use this army to gain control over half of Europe.

Napoleon’s campaigns did not only inflict defeats on European nations, but also caused tremendous suffering. At the same time, the victories of France brought new ideas, among them the French currency, the Franc.

These coins achieved monetary unity of France; the French franc was in use all over the country. It was organized according to the decimal system. Hence, one franc was divided into 100 centimes. France had not invented this rational system, though; Peter the Great (Tsar of Russia 1682–1725) had created his new currency according to this principle. But the French conquests spread the system, which made the use of coins much easier, over Europe.

By the way, the term “franc” is very old. The first coin of the same name was struck in 1360 in order to pay the ransom for the French king who had fallen into the hands of the English king. The inscription on the obverse contained the title “REX FRANCORUM” (lat. for king of the Franks), out of which the name of the coin developed.

France, Napoleon, First Consul of the French government 1799-1804, 5 francs, silver (25.0 g), Paris, year 8 (= 1799)

The French representatives did not only reorganize the currency. They also replaced the old calendar, which they felt to be too ecclesiastical. That is why it says “year 8” on our coin. This date refers to the revolutionary era, which started on July 14, 1789, the day the Bastille was stormed.

The year was divided not in weeks, but in decades – the French applied the same rational system they had introduced for their currency, which, by the way, did not only consist of francs and centimes, but of “décimes”, pieces of 10 centimes, as well.

This coin type, created as the first 5 francs coin of the French Revolution in 1795, was struck by Napoleon for the last time in 1802/3 (= year 11). The coin celebrates revolutionary ideals on its reverse. The personification of Liberty holding the Phrygian cap on a long staff stands left, the personification of reason with angle and perpendicular right. Hercules is found between them. Since his choice of living an exhausting but virtuous life generally was perceived as exemplary, his picture was often used figuratively by artists.

During the first half of the 19th century, the franc spread widely due to the immense importance of the French economy. It became the basis of the Latin Monetary Union, which France, Belgium, Italy, and Switzerland concluded on December 23, 1865. In 1868, Greece joined it. The contract laid down the binding standards according to which the coins had to be struck if they were to circulate within all participating nations. The Latin Monetary Union was successful to such a degree that politicians from several European states, from the US, Russia and the Ottoman Empire met during the World Currency Conference of 1867 in order to think about making the franc the universal world currency. These plans were thwarted by the opposition of England and Prussia.

Nevertheless, the franc remained one of the most important trading currencies until the dollar outstripped it after World War I.

Pound Sterling

The British Empire before 1900

In 1769, Watt invented the steam engine; in 1785, Cartwright’s power loom followed. The two machines facilitated an enormous increase in the production of cheap textiles. England produced more cloth than it could sell at home and in Europe. There was a clear demand for new markets and thus the English government supported the intensification of already existing trading connections. Private trading companies became top dogs on the foreign markets. It was only after the English queen had been crowned empress of India that the British (trading) Empire was consolidated systematically as a part of Great Britain. In 1909, the English queen ruled over about 23 % of the world’s population.

England, John, king of England 1199-1216, penny (= sterling), silver

Offa of Mercia / England († 796) followed the Carolingian monetary reform as early as the 8th century. He divided the pound of silver – not the modern pound, of course, but the so-called tower pound of 349.9 g – in 240 pennies, the latter being the only coins to be struck. The present-day term “pound sterling” is nearly as old as that. In the second half of the 12th century, Henry II (king of England 1154–1189) created a coin, which later was to be called sterling. Thus a pound sterling stood for nothing else than for a pound of 240 pennies – even if today’s pound has consisted of only 100 pennies since the currency conversion in 1971.

Our coin was struck under the reign of the luckless John Lackland. His successor replaced the short cross on the coin’s reverse by a long one in order to impede the customary practice of clipping silver from a coin’s edge.

England, Elizabeth I, queen of England 1558-1603, shilling (16.17 g), silver, 1591

Whereas in the course of the Early and High Middle Ages, large amounts were paid in raw silver weighed on a scale, heavier silver coins prevailed on the market in the Late Middle Ages (cf. part II). Henry VII, the first Tudor king, introduced the shilling valued at twelve pennies in England after the Wars of the Roses. Until then, the shilling had been a unit for calculations only. Henry had his own portrait cut into the obverse dies – a usual practice at the time, derived from Italy.

England, Elizabeth I, queen of England 1558-1603, sovereign valued at 30 shillings, gold, 1583-1600

Henry VII did not only introduce the shilling, he also invented a gold coin valued at 20 shillings, which corresponded to the unit of account “pound”. This coin showed the monarch sitting enthroned on the obverse. No wonder this representative coin type went down in history as a sovereign.

Elizabeth I, his granddaughter, issued two varieties of this heavy gold coin: The sovereign valued at 20 shillings featuring her bust in profile on the obverse and a heavier sovereign valued at 30 shillings which is shown here.

This magnificent gold coin bears testimony to the first heyday of England, when courageous seamen like Francis Drake sailed the Seven Seas, discovered new countries, and the English fleet defeated the Spanish Armada.

Elizabeth I realized a comprehensive coin reform in cooperation with her counselor Sir Thomas Gresham. She systematically replaced all old coins that did not contain enough silver by new ones with a higher silver content.

England, George III, king of England 1760-1820, sovereign, gold

The financial burdens of the war against Napoleon led to a situation where a reform of the English currency was overdue. In 1816, it was realized. The golden sovereign valued at a pound became a regularly issued coinage and the most important nominal. The immense expansion of the British Empire caused the sovereign to become the most important trading coin of the world in the 19th and beginning 20th century. The most important silver coin, a 5 crown piece, was struck in sterling silver, i.e. the coin had a purity of 925/1000.

For the design, the patron saint of England was chosen: St. George slaying the dragon. Benedetto Pistrucci, an Italian artist working at the mint of London, created the popular coin type. Bullion coins featuring St. George have been struck in the Royal Mint until this very day.

US-Dollar

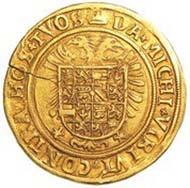

Separation or Unity? – The American Civil War

The American Civil War (1861–1865), the war between the United States (“Union”) and the Confederate States (“Confederacy”) of America justified with the struggle for abolishing or maintaining slavery cost the lives of more Americans than any other war in the history of the United States. Still today, it is engraved in the collective memory of all Americans.

The Civil War initiated important economic changes, which have set the tone of the American economic history for many years: The industrialized North had won the victory over the South, traditionally a rural area. After the war, the Union forced its economic system upon the defeated Confederate States. At the same time, the administration was centralized and numerous privileges of the federal states were abolished; Congress, for example, imposed the first national income tax at that time.

USA, 1 dollar, silver (26.96 g), Philadelphia, 1799

In 1792, Congress passed the mint act, which regulated the coinage system of the country. On this occasion, the dollar was declared official currency of the USA. As to its weight and silver content, it depended on the Spanish reales de a ocho, which were called “dollars” and circulated in large quantities in the US.

In 1794, Philadelphia, the first mint of the US started to strike coins. Congress had agreed upon the fact that the coin’s obverse should not show the portrait of the president, but a personification of Liberty. She is surrounded by stars, whose number refers to the number of states that were members of the USA at that time. Two elements of the reverse were made compulsory: the eagle, heraldic animal of the US, and the inscription “UNITED STATES OF AMERICA”.

USA, 1 trade dollar, silver (27.2 g), San Francisco, 1875

The trade dollar was the American answer to European coins circulating in the Far East. It was struck solely for trade with China, Japan and Korea and its silver content was slightly higher than the one of regular coins.

Its obverse presented Lady Liberty pointing to the left, i.e. to the West where China was located, with an olive spray, symbol of peace.

The Dollar becomes the World Currency

In the late 19th century, the American economic system was shaken by crises and price declines. On December 23, 1913, Congress founded a system of privately controlled and locally oriented central banks to cushion the ups and downs. These banks were united in the Federal Reserve Bank, which in turn was under the supervision of the State. Even today, all banks with a head office located in the USA have to be members of the Federal Reserve System and have to supply a certain amount of money free-of-interest to their local central bank.

The Federal Reserve Bank is responsible for controlling the amount of money in circulation. It decides how many dollar bills will be printed each year, how many coins will be struck. Moreover, it maintains money reserves, which can be reduced or enlarged if required in order to react quickly to the needs of the market.

The new currency of the United States, the Federal Reserve Note, popularly called “greenback”, was introduced along with the Federal Reserve Bank. The Gold Standard Act of 1900 backed these bank notes by gold. Bank notes, gold and silver coins were issued at the same time and circulated side by side.

It was not before the Great Depression of 1929 that a change of policy became necessary. Considering the huge masses of unemployed, President Theodore Roosevelt decided to raise funds to overcome the crisis with the help of a limited inflation. To this end, he devalued the dollar by 40.34 % and forbade the circulation of gold coins at the same time. In addition to that, he enacted a law, which made the possession of gold and gold coins a punishable offense for private persons. It was not before 1971 that this law was repealed. The dollar was backed by gold only in the international sphere.

This was the basic requirement for the dollar to become the World’s reserve currency in the Bretton Woods Agreements. At the end of World War II, the European Allies of the United States depended on generous dollar loans to finance reconstruction. That was the reason why the 32 signatory states agreed to accept every dollar presented to their central banks at a value of 35 dollar the ounce of gold. At the same time, many banks replaced their gold reserves by dollar reserves.

These circumstances have fixed the dollar exchange rate for many years. It was not before 1971 when the gold standard was abolished that the US-dollar became a free-floating currency in competition with other national currencies.

USA, 20 $, gold (33.4 g), 1924

It happened at a casual lunch in 1905: The president of the United States of America, Theodore Roosevelt, talked about the “atrocious hideousness” of American coins to the famous artist Augustus Saint-Gaudens. This informal table talk was the initial spark for the artist to design a coin which was to be known as the most beautiful American coinage ever.

Being backed by the president himself, Saint-Gaudens was able to realize his artistic conception despite strong resistance on the part of the State mint: a Lady Liberty, the personification of freedom, seen from the front and of high relief. In August 1907, only 12.000 specimens were struck according the original draft. Then, even the president had to admit that the design of the artist was not qualified for mass production: Up to 11 processes of striking were necessary to obtain the relief as requested.

In the meantime, the artist had died, so Charles Barber, the official die engraver and Saint-Gaudens’ antagonist, had the chance to adapt the artistic conception to the technical demands. He created a coin design which was not the “most beautiful ever”, but proved to be very useful. The Double Eagle was struck until 1933.

Euro

Europe in our World

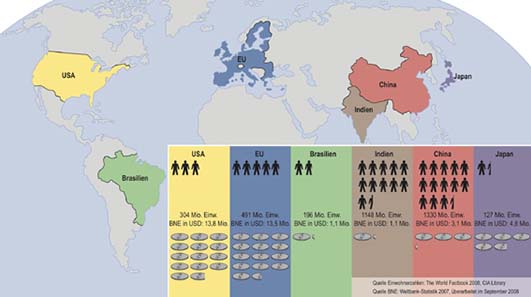

Europe has witnessed countless wars and it is much to be hoped that its citizens have learned from that. It is not important to stress the differences between the nations in modern Europe, but rather to find a common identity as Europeans. The European Single Market turns French and English, Spanish and Italian, Polish and German members into one single economic community – a first step to a peaceful united continent. Europe, lacking in mineral and other natural resources, will only be able to hold its ground against giants like the USA and China if it is united.

A European Central Bank and the introduction of the Euro as an accounting currency in 1999 and as physical money in 2002 are the basis for a strong European market.

When the delegates of Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, Luxemburg and the Netherlands signed the Treaty of Rome, establishing the European Economic Community (EEC) on March 25, 1957, they dreamed of the creation of a common market for all nations participating. Today, about 50 years later, all expectations are exceeded by far. More than twenty additional nations have joined the six signers of the Roman Treaty; a number of others are negotiating at the moment for a potential membership.

All members of the EU have access to a free labor market and a single market not hindered by customs barriers. Natives as well as EU-citizens are granted the right of equal treatment.

States who have qualified by a low rate of inflation and a balanced national budget have the possibility to launch the Euro as their currency. At present, it is in circulation in sixteen European countries. Since its introduction, the European currency has set up as a strong, worldwide reserve currency beside the dollar.

This was the last part of our series. You can find the previous articles in the archive: Part I and Part II.