With the fall of metallic-backed currency systems, a crisis in managed currency systems, and the rise of cryptocurrencies, now – more than ever before – we need a primer to guide us as we think about money. What is money, where does it come from, why do we have it, and what does it do? Almost continuously in use since its invention, money undoubtedly ranks alongside law as one of the greatest socially constructed creations of our earliest civilizations. And yet, millennia on, it is generally recognized that the social sciences, economic science, and sociology are all struggling to conceptualize money in our rapidly changing world.

Why are we so unsure about something that has been an important part of our lives for millennia? Part of the difficulty we have in understanding money might be explained by its complex and dynamic nature, the various forms it acquires, and its inter-related socio-economic functions. Moreover, money is created as a component of larger, over-arching monetary systems, and its interconnectedness may make it hard to conceptualize in its true historical context. Or is it simply that most of us use money every day unthinkingly, without too much trouble, and surmise that we know enough about it to get by in most situations? Whatever the case, one thing is very clear: revolutionary monetary innovations and global pandemics threaten to change the way we conceptualize and use money in the twenty-first century.

Three Functions of Money

The primary functions of money appear to almost be universally recognized by orthodox monetary theorists. What we now call “money” must serve as a medium of exchange, a store of value, and as a measure of value. As uncontroversial as this may seem to be, our understanding of the history of money is not nearly so cut and dried, and is often distinguished by academic rivalry and ideological conflict. Many different kinds of monies have performed different key functions at different times, but for historians context is everything.

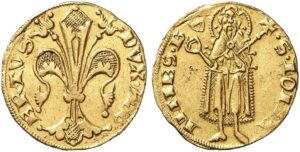

The medium of exchange function is a logical place to start the discussion. Money is presented as a tangible, universal commodity exchangeable for all other commodities. Its value is only established in exchange, and must be able to finalize a transaction as a means of payment (or settlement). It follows that money, as a tangible, universal commodity, should also act as a store of value. Money that best exemplifies these two functions has historically been cowrie shells and precious metal coins of gold, silver, and copper; but all kinds of cattle and grain, along with salt, pepper, spices, and many other commodities have served as monies until quite recent times.

In contrast, the measure of value or “unit-of-account” function creates intangible monies. Ever since the creation of the first temple ledgers in Babylon, at least 4,500 years ago, money has been imagined and used as an abstract a measure of value to create credits and debts. Just as in the bank accounts of today, these kind of unit-of-accounting monies are not some kind of ‘neutral’ commodities, but rather the result of carefully constructed social and political arrangements. The creation of (monetary) units and laws signifies the birth of our first civilizations, and helps explain the almost continuous rise of cities, and indeed their socioeconomic dominance today, some five millennia or so later.

Problematically, if an item must always simultaneously exhibit the above three tangible and intangible functions to be considered real “money” then many scholars would argue that our understanding of history needs to be radically revised, for there are times and places where no completely functional monies appear to have been in circulation at all. And that is if we can somehow theorize or rationalize our way into thinking that monies can be at once both tangible and intangible, which is logically impossible. Moreover, the rise of cryptocurrencies or “digital monies” seriously challenge – or undermine – functional conceptions of money, and promote the use of looser “working definitions” of currencies and markets. Just as troubling, conventional monetary theory does not generally acknowledge the existence of other possible monetary functions.

And Another Three Functions of Money

In addition to the three key monetary functions outlined above, in the past and in the present, money has had other functions which are often ignored in conventional monetary theory. Historically, monies have often been required to serve as standards of value, that is as tangible objects retaining stable values, over time. Typically, silver and gold served as monetary standards by which the market value of prescribed weight and purity of a precious metal served as benchmark “anchor” or “peg” against which all other market values were calculated. So during the classical age of gold and silver standards, precious metals were not necessarily used as a means of payment, but instead as a tangible standard of value from which all values across the economy could be “resolved” or determined.

It may be harder to conceptualize the way in which money functions as an intangible link monies, and as an intangible measure of relative values. Using historical examples of link monies, such as the ancient Mesopotamian shekel, the Roman denarii communes, and also the Dutch Rixdollar, these hypothetical link monies allowed for value to be measured and calculated between themselves and other tangible monies in circulation (as mediums of exchange), or other intangible monies. For example, the intangible Rixdollar, representing one defined weight and purity of silver, was a link money tied to another intangible unit-of-accounting money, the guilder, which represented a different weight and purity of silver. However clumsy the arrangement may sound to us, the Rixdollar/guilder link was the monetary foundation of Dutch accounting for almost a century during the 16th and 17th centuries.

Finally, we turn to the measure of relative values (MRV) function, so crucial for orthodox, and indeed heterodox, economic because all “prices” are expressed (often uncritically and even unthinkingly) in these terms. It is an intangible, and entirely necessary, measuring device in today’s microeconomic analysis, and money is used as a measure of relative value in every economics textbook. In effect, economists employ an intangible measure in order to quantify (think about) the relative values of tangible goods and services in an economy.

We have now completed a simplified outline of a three-plus-three “six functions” approach, as pioneered by Dennis O. Flynn:

The Six Historical Functions of Monies:

- Unit of Accounting* (intangible)

- Medium of Exchange* (tangible)

- Store of Value* (tangible)

- Standard of Value (tangible)

- Link Money (intangible)

- Measure of Relative Values (intangible)

Critically, the six functions approach strives to distinguish between the inter-related tangible and intangible functions of monies. Conflated explanations of what “money” does are disaggregated “in the extreme” to facilitate understanding. Anything that does any of the above six functions may be thought of as “money” of some kind. Money is no longer conceptualized as an idealized, functional hybrid of the first three functions, and so a new “price theory of monies” can be developed for cryptocurrencies, just as readily as it can be for cowrie shells or gold coins.

Towards a new understanding

In conclusion, the above article has introduced (in a radically truncated manner) six key tangible and intangible functions of money; briefly explaining what money does, what money is, and what money might be in an uncertain age of global pandemics and emerging socioeconomic crises. Now more than ever, the emerging financial crises forces us to fundamentally reconsider how we conceive the use and importance of money, not only across whole economies and societies, but also in our own lives.

Let’s continue the conversation!

Please look out for the next article in this Numismatist’s Guide to Money series, Theories of Money, where Simon Bytheway examines archeological discoveries and the earliest historical records to find out what they tell us about the competing commodity and claim theories, and the wider socio-economic meaning of money.

Author’s note: The thoughts presented here are based on my earlier “Conceptualizing Money: from Commodity Monies to Cryptocurrencies” (2017) article, with thanks to the editors and publishers. I hope to present a full bibliography of sources and additional readings at the conclusion of the Numismatist’s Guide to Money series.

For more information on the author, read Simon Bytheway’s Who’s who entry.

You may also like his analysis of gold in James Bond’s Goldfinger movie or on the Decimalisation of the British currency.