by Björn Schöpe

After a week feasted away, young William Lloyd lost control. On February 7, 1845, he grabbed a sculpture and tossed it on a glass showcase in the British Museum. The showcase burst and with it the cameo glass vase on display within a private collector had given to the museum as a loan. Applying legal tricks, Lloyd’s lawyer accomplished that his client was sentenced to pay a fine of three Pounds – for destroying the showcase!

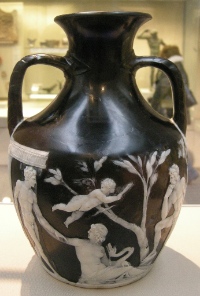

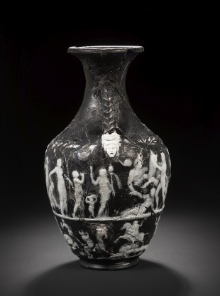

The Portland Vase, today on display in the British Museum. Photograph: Wikipedia (sailko).

After the unfortunate incident the vase was put together again. Afterwards, however, it continued to be not really appreciated. For three years, it was up on sale with Christie’s without even reaching the minimum price. Finally, in 1945, the British Museum acquired the piece. Today the vase, held in such low esteem once, is presented with great pride: the Portland Vase has become one of the most famous ancient works of art whose interpretation is hotly disputed. If it is authentic, that is … Even that was controverted recently!

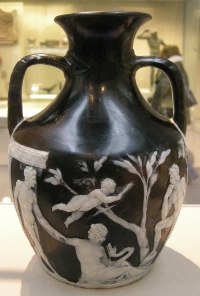

Detail of the Portland Vase. Photograph: Wikipedia (Marie-Lan Nguyen).

To answer the questions about the workshop or the date the provenance is of no help, unfortunately. The vase is said to have been found in a sarcophagus from the 3rd cent. A. D., near the mausoleum of Alexander Severus in Rome. From the late 16th century onwards, it was on display in the Roman Palazzo Madama, before it went into the possession of the Barberini in 1642 and, eventually, reached England and the house of the Duchess of Portland after which the vase was named. Since 1810, the piece is marveled at by the visitors of the British Museum, where it was on display from 1945 onwards as a loan until it was acquired.

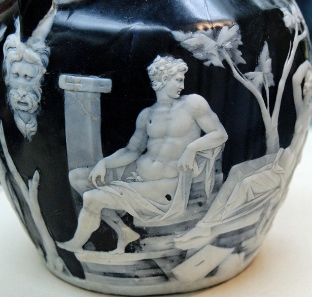

Detail of the Portland Vase. Photograph: Wikipedia (Marie-Lan Nguyen).

The vase is just 24 cm high and almost 18 cm wide and puzzles the viewer right at the first sight. Ancient amphorae usually stand on a foot. This, however, is missing with the glass work of art that stands on a simple base plate. Until now, it wasn’t clear if such a foot was removed already in antiquity, if it ever existed in the first place or, rather, is indicative of a contemporary date; this, too, seems to be solved by a new discovery. The vase is made of dark-blue glass on which a layer of white glass was applied. This white layer was worked on in a very elaborate and rare cameo technique, meaning the artist cut as much as it took to make the white figures stand out against a dark background in the end.

Detail of the Portland Vase. Photograph: Wikipedia (Marie-Lan Nguyen).

These very figures cause the viewer headache from the year dot. Usually, in ancient art people are interpreted on the basis of the objects they are holding or the clothes they are wearing. Such attributes, which were deliberately added by the artists, aid in assigning individual names. Certain ways of representation, like the ‘heroic nudity’, for instance, point to a supernatural being.

The vase is almost totally lacking such explicit attributes. This shortcoming made it possible for the interpreters to suggest readings that seems almost random. Some years ago, a researcher compiled more than fifty different readings of the scenes and, resigning, reached the conclusion that a definitive interpretation is hardly possible. That, however, wasn’t met with approval in the academic community: since that time, some more hypotheses have been put forward.

Detail of the Portland Vase. Photograph: Wikipedia (Jastrow).

All attempts to establish a logical connection between the scenes divide into two groups: some interpret the depiction purely mythological, while others favor a political-historical interpretation. At least the date to early Augustan times, around 30/20 B.C., as suggested by Erika Simon in the 1950s due to stylistic reasons, is largely and for good reasons accepted.

Due to the lack of attributes and the scenery that allows the most diverse readings, the suggestions put forward for an unambiguous reading of the depictions are always tinged with arbitrariness. As long as the interpretation was based solely on the vase, hardly any new arguments could be found.

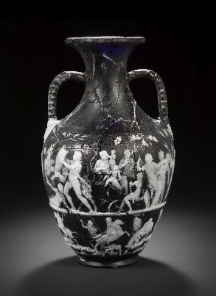

But now a comparable piece has appeared in an old private collection. The auction house Bonham’s presented the piece, 33.5 cm high, in September 2009 on the “18th Congress of the International Association for the History of Glass”.

In contrast to the Portland Case, the Bonhams Vase displays a second smaller frieze under the main register under which a flat base is situated. Thus, it may seem safe to assume that the Portland Vase likewise must be reconstructed in a similar manner – as was again and again suggested. Presumably the vase lost its lower part already in antiquity.

Based on this important new member amongst the cameo vessels, archaeologist and art dealer Hans-Christoph von Mosch put forward an entirely new reading of the Portland Vase. This new reading has the merit of being based not solely on the vase but, finally, on exterior arguments. Until now, that wasn’t possible due to the lack of comparable pieces. Stylistic and technical similarities suggest a connection between the two pieces. At least, they seem to be contemporaneous, or even were made in the same workshop. The masks below the handles are indicative of the theatrical sphere: the sides of the Portland Vase are decorated with faces of Pan, whereas under the handles of the Bonhams Vase unbearded tragical theatermasks are attached.

none

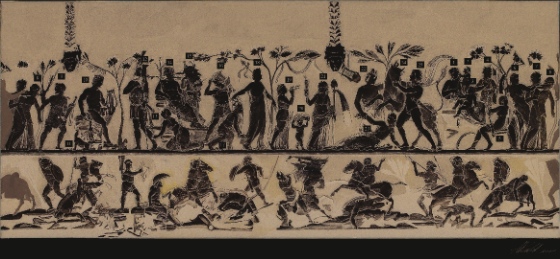

Bonhams Vase, front side: Scene of birth etc. (press photo Bonhams, London; by courtesy of the owner of the vase).

But what interesting things are shown on the new vase after all? Fortunately, the subject can be ascertained here without doubt. There is going to be no argument about the frieze depicting the myth of Antiope. Antiope was one of the many mistresses of Zeus. She bore him twins, Amphion and Zethos, which were exposed in the Kithairon Mountain – as is often the case there existed different explanations for that, in accordance with the frequency of a peaceful coexistence of many variants of one and the same subject in Greek mythology. This richness of variants makes it possible to read the Bonham’s Vase not a random illustration of the myth but to associate it with a very distinct tragedy, that is Euripes’ “Antiope” of which only fragments have come down to us.

Antiope is forced to do slave labor for her aunt Dirke, but she manages to escapes and comes across her sons in the mountain. The opposed young men – Amphion as lyre-playing aesthete and the roll-your-sleeves-up hunter Zethos – have no idea who they are facing, in contrast to Antiope who instantly recognizes her sons. They decide to hand Antiope over to Dirke. When Dirke requires them to severely punish her runaway slave, a shepherd reveals them the truth. The men take revenge on Dirke, let a bull trample her and dragged her to death. The artistic realization of that horrible death recalls in its composition a larger-than-life sculptural group from Rhodes, today on display in Naples, that was brought to Rome as late as 42 B. C. The date of the vase, therefore, to the 30s or 20s can be considered confirmed.

Bonhams Vase, back side: Kithairon etc. (press photo Bonhams, London; by courtesy of the owner of the vase).

The artist condenses this narrative, which has plenty of dramatic elements, on both sides of the Bonhams Vase in a ‘triptychon arrangement’: in the focus on each side is a main scene the viewer has to read in connection with the adjacent scenes in order to understand the message. Each of these episodes includes Antiope and all tell essential elements of the story. Three aspects of the layout are revealing; on the one hand the connection between the two friezes. The lower one depicts an amazonomachy, i.e. a fight between Greeks and amazons. The Antiope myth, in contrast, includes no amazons. Von Mosch has found the decisive clue to this, which sits in the form of an amazon, as minor character, in the main frieze. This amazon is Antiope as well – but an amazon queen bearing the same name! Amazonomachies were a popular motif in the layout of such lower friezes. The artist here successfully establishes a sophisticated but, in the regard to the content, basically unnecessary connection.

Bonhams Vase, side view: Oreibasia and death of Dirke (press photo Bonhams, London; by courtesy of the owner of the vase).

The two following observation of von Mosch are far-reaching not only for the reading of this object but for the Portland Vase, too. Firstly, the Bonhams Vase shows that on its counterpart likewise the two sides ought to be read together. They simply cannot be two separate scenes. Secondly, on the new vase there is a procession moving through one of the scenes, matching the masks on the sides which point to the theater which is related to Dionysos. In this procession, which, according to its execution, is part of the legendary Mysteries of Dionysos, the sons of Antiope submit their mother for punishment. Already a long time ago, Erika Simon has found out that almost all cameo glass of that period of time deal with Dionysiac subjects. For the Portland Vase an explanation from this mythical world is much more likely than a short-term political means of defamation.

According to a popular interpretation, the latter reads as follows: Atia, mother of Octavian, future emperor Augustus, is depicted twice. On the one side she lies under a fig tree on stone slabs. Apollo approaches her to conceive with her Rome’s ruler to be, in the presence of his sister Artemis. On the other side, the version is shown as it was told in ancient literature as rumor going round: Atia lies under a tree and unites with Apollo in the form of a snake. Eros as symbol of love is hovering above. At the same time, again Apollo is standing-by in human form, and old, consecrated founder of Rome, Mars-Quirinus looks on. The identification of the characters, however, is solely based on the snake and Amor, which admittedly are connected with the anecdote of that time. There are no attributes present – any satisfying reasons for their absence are lacking, too.

Bonhams Vase, side view: Seizure of Antiope and dialogue of the twins (press photo Bonhams, London; by courtesy of the owner of the vase).

When the splendorous vessel is seen against this background, as von Mosch does, its interpretation seems much more convincing. According to him, a Dionysiac subject (think of the masks of Pan under the handles) in the wider sense is illustrated here – as on the Bonhams Vase – as is often the case with cameo glass. The scenes are calmer and seemingly simpler designed than on the Bonhams Vase: two groups of three are shown here. The persons are sitting, standing and lying. There is hardly any action present. Only the woman with the snake touches a person approaching while Eros hovers above them.

Von Mosch identifies the foundation myth of the city of Thebes as subject of the vessel. Kadmos, a Greek hero, kills a dragon of Ares. Goddess Athena ordered him to sow the teeth of the monster. They became huge warriors that killed each other. The last five of them, together with Kadmos, built the city of Thebes that was named Kadmeia at first after its founder. Zeus gave him Harmonia as his wife, daughter of Ares and Aphrodite.

Eros here hints at a romantic relationship between the man and the woman, the snake is indicative of the monster of Ares whose daughter is reclining Harmonia. Kadmos wards off the snake with one hand, and let himself be pulled towards his wife with the other. A building indicated in the background might well be regarded a source of Ares at which Kadmos accomplished his heroic deed, or the palace of Kadmos in which the newly-wed couple finally retreats to the bedroom. The naked onlooker deliberately has no attributes: most probably he indicates the multiple divine origins of the wedding. Poseidon was the father of Kadmos, Zeus had made the union possible and was his great-great-grandfather. The viewer of the vase might well see both in the man.

The second side becomes accessible when, based on this interpretation, the place is brought into question. The slabs conform to the usual definition of a rock or a mountain, respectively. Here, Kadmeia is hinted at, acropolis hill of Thebes, on which sanctuaries of Semele, Ares and Aphrodite were situated. These very three are sitting on the rock. The scenery reminds a bit of the Romantic areas of ruins common on vedutas of Rome of the 18th century. Parts of building symbolize the ruins of sanctuaries and the palace on Kadmeia. Reclining Semele is the result of the union between Kamod and Harmonia who can be seen on the other side. Hence, at the same time Harmonia is grandchild of the deities on the maternal side who are sitting next to her. Being sad, she already holds the torch of the Underworld; she is about to be killed by the thunderbolt of Zeus who therewith unites with her for good. The child that will be born from this strike of lightning is the god Dionysos.

And so the circle is complete. Both sides deal with the foundation legend of Thebes, are connected in more than one way, and have to be seen as a multi-layered affair. The Portland Vase depicts the wedding of Kadmos and Harmonia, the first wedding on earth. Gods and humans participate, and the Charites sang: “What is beautiful we hold dear and what is not beautiful we do not hold dear.“ The “beautiful” is a central term in the Mysteries of Dionysos and recalls the connection between marriage and death as it was celebrated on Roman sarcophagi – after all, the Portland Vase allegedly was found in one of these.

Drawing of the vase from a private collection presented by Bonham. The figures are: 1-3 Antiope and her children; 4 wet nurse or Eileithyia, goddess of childbirth; 5 unexplained; 6 Dirke; 7 Amphion; 8 Antiope; 9 Zethos; 10 Amphion; 11 hunting dog; 12 Zethos; 13 Antiope; 14 Kithairon; 15 his wife and one of the Erinyes called Tisiphone, or Megaira; 16-21 procession of the mystes of Dionysos: satyr (16), female servant (17), Dirke (18), female flute player (19), boy with liknon (20); 21 Antiope; 22 Amphion; 23 Dirke; 24 bull; 25 Zethos. Drawing by Alexander Valdmann, New York. © Hans-Christoph von Mosch.

The myth of Antiope on the Bonhams Vase shows side by side the birth (the twins) and death (of Dirke). Death, however, is visually related to the mystic procession so that the viewer might well have associated a wedding procession: the union of Dionysos on the form of a bull with Dirke, who is killed in the process. Semele is nothing different, since her encounter with Zeus – and creates new life all the same.

Marriage topics frequently occur on other glass amphorae as well. Thus, is it safe to assume such a context for the two magnificent vases. No portrait features on the characters’ faces refer to the scheming of the politics of the day at court. These precious vases, being full of sophisticated hints, are much more likely to be wedding presents amongst members of the Roman upper class. This intellectually trained audience was able to understand the translation of material from Greek tragedies from the 5th century and to recognize many more things in addition.

Thanks to the Bonhams Vase we finally und fully understand the multi-layered program of the Portland Vase. Since such interpretations can’t be verified with mathematical accuracy the discussion is likely to continue after all; the iconographic program is too complex and rich in hints.

We needn’t worry about the future of the Portland Vase, by contrast, if the vision of British science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke comes true: in his short story “All the time of the World” time travelers rescue the glass testimony of the human past just in time before earth is destroyed. Who knows if they are aware of its history of interpretation? In space, at the latest, the discussion is likely to be rekindled again.

The article by Hans-Christoph von Mosch, „ ‚Outdoorsex‘ unter dem Pfirsichbaum? Die Portlandvase im Lichte einer sensationellen Entdeckung“ (written in German), you may download for free as pfd file.

Today the British Museum presents the Portland Vase as one of its highlights on its website.