Quite rightly, China prides itself of its long history, impressively evidenced by the Chinese monetary tradition that took a different route than our western one. The third episode is about the invention of the paper money and the introduction of a coinage following the western model.

Once it doesn’t matter what weight a coin has and what metal it consists of, when only its nominal value is of interest anymore, then it is but a small step from a real coin to the book currency. As a matter of fact, Chinese merchants invented the bill already at the turn from of the 8th to the 9th century, i.e. about 300 earlier than their western colleagues. The bill’s underlying idea is to deposit a certain sum at the local merchants’ guild and to receive a receipt that could be exchanged at the merchants’ guild at another town. The guilds settled the sums paid and hence spared themselves the tedious and dangerous transport of cash money.

The government prohibited that custom as early as 841. It wanted to monopolize the issue of paper money. After all, that was the easiest kind of creation of value. Thus, under Emperor Zhenzong (997-1022) the first official paper money of the world was designed. He had notes printed worth 1 to 10 ‘guan’ (= strings) that equaled 1,000 cash and 10,000 cash, respectively. Upon redemption, only a part of it was actually paid. One ‘guan jiaozi’ (= official note), whose nominal value was one ‘guan’ (= string, i.e. 1000 cash), was discharged for 770 cash.

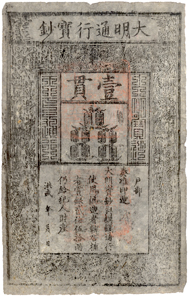

China. Ming Dynasty. Emperor Tai Zu (1368-1398), note worth 1,000 cash. The value of this bank note is specified by the 10 strings depicted on it, worth 100 cash each. © MoneyMuseum, Zurich.

As a matter of course, in China, too, this means of payment only serves its purpose as long as it is backed up by an economically prosperous government. While the cash, regardless of their date of issue, circulated simultaneously, the official paper money was subject to inflation and recalls.

Paper and silver

More than 100 million people had been submitted by the Mongols under Genghis Khan. Not only China was part of their empire, but the Near East as well, the Balkans, Russia and Armenia. These countries all had a different tradition of money than the Middle Kingdom. There was no such thing as fiat currency, but simply coins whose nominal value was identically equal to their intrinsic value. No wonder, then, that the Mongols regarded the ‘valueless’ cash coins no suitable basis for a healthy economy.

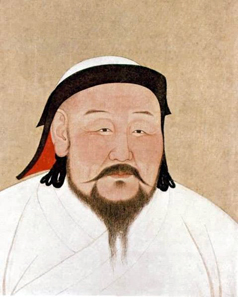

Khubilai Khan (1260-1294).

Hence, Khubilai Khan (1260-1294) started a broad monetary reform immediately after his accession to the throne in 1260 which linked the Chinese currency system to the silver price. He had two kinds of paper money printed: the ‘jiaochao’ and the ‘Zhong Tong yuan-bao jiaochao’. The first was based on a silk reserve in the royal treasure vaults. There, a ‘jiaochao’ worth 1,000 liang could be exchanged for 50 silver liang or 1.950 kilos, respectively. The ‘Zhong Tong yuanbao’ (= official note of the Zhong Dynasty) was issued in cash and backed up by a silver reserve (1,000 cash equaled 39 grams silver).

Whereas the ‘jiaochao’ disappeared off the payments rather quickly, the ‘Zhong Tong yuanbao’ became one of the most stable currency ever circulating in China – the traveler Marco Polo reported, quite amazed by it: “When any of the cards are torn or spoiled the owner carries them to the place whence they were issued and receives fresh ones with a deduction of 3 per cent. If a man wishes gold or silver to make plate girdles or other ornaments, he goes to the office carrying a sufficient number of cards and gives them in payment for the quantity which he requires. The entire army of the khan is paid for with this kind of money.”

China. Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), silver ingots worth 10 liang. © MoneyMuseum, Zurich.

When a paper currency is based on a silver unit, it is but a small step to the silver currency being produced for real. In China, however, this step wasn’t taken by the government but by private economy. The merchants’ guilds and the Chinese state had produced silver ingots and used it as reserve capital as early as the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Silver bars were accepted by the Chinese government as a means to pay taxes and it comes as no surprise that the production of these bars were subject to strict laws: every single ingot had to be signed by name by the commissioning party as well as the manufacturer; plus, the year as well as the place of production had to be specified. This was the only way the government made sure that, if the quality or the weight of an ingot was improper, the ones responsible were punished.

As late as 1834, J. R. Morrison wrote in his ‘China Commercial Guide’: “The refined silver is cast into ingots, and stamped with the names of the banker and the workmen, the year and district in which it is cast, and sometimes the kind of tax for which it was cast to pay. Should any deception be afterwards discovered, at whatever distance of time, the refiner is liable to severe punishment.”

The influence of the west

From the 16th century onwards, western merchants tried to establish trade links with China. The goods that had been transported for centuries in rather small quantities across the Silk Road were just too tempting.

Chinoiserie: lanscape with mandarin tree. Vicenza. Fresco painting by Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo 1757. Source: Wikipedia / The Yorck Project

One such good was the tea that came to be quite trendy in England since the 17th century at the latest. And there was silk, of course, and all the other precious items which European dealers tried to copy, demonstrating more or less skill.

Spain. Real de a ocho from 1808 with Chinese counter-stamps. © MoneyMuseum, Zurich.

Europe had nothing really useful to offer to the Chinese, in turn. And so they demanded silver for their goods. It was particularly Spanish coins that circulated in China, as a kind of ‘mini-ingot’. The Spanish had set foot on the Philippines already in 1564. Via Manila as their most important staging post they imported silver from Mexico and the Andes in the shape of 4 and 8 reales coins to China in order to receive the coveted luxury items there. The 8 reales coins were especially popular in China because of their average finesses of 935/1000 which was almost identical to the Chinese standard ‘wenyin’ (937/1000).

This is why the Spanish coins appeared quite frequently in the commercial life of the Chinese who referred to them as ‘benyang’ (= standard piaster). They were used by the merchants, who had checked and counter-stamped them first. There were even Chinese manuals published in which all these foreign coins were sketchily drawn and specified with information on nominal weight and silver fineness.

During the decline of the Chinese central government, when it was forced to pay the salary of its civil servants in bank notes which could no longer be exchanged for silver, some private companies started to issue their own dollars, of course entirely unofficially but tolerated all the same.

This is how J. P. Morrison, in his book on Chinese currencies from 1844, wrote about it: “In the district of Shunteh, in the south of Canton, there is said to be a very large establishment, in which as many as a hundred workmen are frequently employed. Dollars are there manufactured at all gradations of value … These false coiners are said to possess European stamps, procured at great expense; but sometimes they attempt imitations in which the omission or disfiguring of some letters easily betray the deception to a European eye. So common, however, are their dollars in circulation that men from this district are most usually selected as shroffs.”

The first Chinese coins

As long as the Spanish government needn’t bother about the amount of silver draining off the country for the acquisition of luxury items, China remained a satisfied trade partner who gladly exchanged its products for noble metal. English politicians, on the other hand, saw the trade with China with different eyes. What they disliked what the fact, apparently, the western market had nothing to offer to a Chinese customer. And so they searched for a product in the entire British Empire that could be put on the Chinese market. The winner was opium that had the advantage that anyone who tasted it a few times got addicted and was willing to pay the high prices for it. Thousands ruined themselves in the Shanghai opium dens – and the Chinese government decided to put an end to that. It intended to prohibit the opium trade. But it bit on granite with the importers.

The British ship HMS Nemesis destroys Chinese junks at the beginning of the First Opium War (1839-1842). Painting by E. Duncan, 1843. Source: Wikipedia.

In the First and Second Opium War the British navy forced China to legalize the opium. Consequently, the English continued their lucrative triangular trade: they brought cheap cotton fabric to India and exchanged it for opium, to trade it in China for the tea England had grown so fond of.

With the Opium Wars the Britons had exerted their influence on the Chinese imperial court. No wonder then that they met no substantial resistance when they brought pressure on China to introduce currency following a western model.

China. Quing Dynasty. Emperor Puyi (1875-1908), dragon dollar 1889. This is one of the first Chinese coins ‘western-style’ – albeit still without any portrait. © MoneyMuseum, Zurich.

Under Puyi, the last emperor, the first ‘western-style’ coins were produced. This was done in 1889, when a mint was established in Canton with coining machines from Birmingham and Göppingen. Dollars, half dollars, 20, 10 as well as 5 cent coins were manufactured there, which, however, didn’t serve as new currency in China but were simply one currency amongst the many foreign ones.

But, as a matter of fact, China had made the decisive step into the western monetary system with that. Today, the country is fully integrated. Coins and notes following the western model, debit cards and bank accounts, and even the human portrait – that found its way into Chinese currency as late as Sun Yat-sen (1866-1925), the first President of the Republic of China – is no longer a taboo.

Numerous examples of the history of Chinese coinage you will find informatively explained on the website of the MoneyMuseum.

Many of these objects in the MoneyMuseum are part of the Kuhn Collection.

An article on the first Chinese coins following the western model you can find – at CoinsWeekly, where else. Please click here.

You can find all parts of this series here.