As we have seen in part 1, the Thirty Years’ War was no religious war but a conflict that was rooted in the complex political situation of Europe, in the divergent interests particularly of France, Spain, the emperor and the Netherlands.

In 1618, nobody really thought it to be possible that a war might break out. It was rather expected for 1621, i.e. for the date the armistice ended the governor general of the Spanish Netherlands had concluded with the United Netherlands. The Spanish king planned a comprehensive military action for 1621, so powerful that the United Netherlands wouldn’t be able to oppose.

Milan. Philipp III of Spain, 1598-1621. Ducatone 1602. From auction sale Künker 206 (2012), 3058.

Securing the supply was of the essence in the preparation of the military strike. By tradition, the House of Habsburg’s main recruitment area was Northern Italy; there, the Spanish king had sufficient tax revenues at his disposal to finance the payment for his soldiers. Thus, a free passage through the Valtelline Valley was necessary, to get to Lake Constance and, along the Rhine River, to the Netherlands. The Spanish would have liked to occupy the Valtelline Valley but they abstained from doing so – after all, they depended on the support of the Swiss confederates for a safe passage through Switzerland. Securing the passageway along the Rhine likewise was of prime importance. Most of the way was in Catholic, hence allied, hand.

Jülich. Uniface hexagonal klippe of 10 thaler 1610, produced during the siege of the Jülich fortress. From auction sale Künker 122 (2007), 4323.

There were a few parts of the way, however, that weren’t controlled by Catholic princes. Those were the ones to be sealed – for which Jülich in 1610 is a case in point. After the reigning Duke Johann Wilhelm von Jülich-Kleve-Berg had died, his legacy was under consideration because there was no heir of male sex.

On the other hand, there was any number of heirs in general: seven ruling houses made a claim to Jülich, Kleve, Berg, Mark, Ravensberg and Ravenstein. The territories in question were dispersed amongst the area between the Dutch border and Cologne. The emperor soon realized – or was made to realize by his Spanish relatives – that the territory at issue was of high importance for securing the Rhine route. Because of that, the emperor immediately sent an army that seized the city of Jülich.

Germany and foreign countries alike protested vehemently. The military strike wasn’t considered as a manifestation of the emperor’s right to act as arbitrator in matters of difference but as a manifestation of the dynastic machtpolitik of the Habsburg family with the aim to nail down an area of strategic importance. That affected the interests of France and the interests of the United Netherlands alike. Both supplied contingents of mercenary soldiers when the margrave of Brandenburg and the duke of Pfalz-Neuburg sent their united troops towards seized Jülich.

Silver medal 1610, by Chr. Maler, on the seizure of the city of Jülich. Weygand Coll. 1428. From auction sale Künker 116 (2007), 4548.

On 1st September 1610, the representatives of the emperor were forced to withdraw. The quarrel on the legacy, however, continued. It wasn’t until four years later that a compromise was reached: the duke of Pfalz-Neuburg, who had converted to a Catholic in the meantime, received Jülich and Berg; the margrave of Brandenburg, who had become a Calvinist in order to make sure of the support of the extreme Protestant party, was given Kleve, Mark and Ravensberg.

Michiel Jansz van Mierevelt, Portrait of Frederick V, 1613. Source: Wikicommons.

The Spanish were well aware that another segment of the way would certainly become something of a problem in 1621. Frederick V, the Calvinist count palatine, controlled roughly 80 kilometers of the Rhine. So, either a treaty and hence an agreement had to be reached with that count palatinate or he had to be liquidated somehow. Did Frederick V know about the precariousness of his situation? At any rate, he played right into the hands of his enemies in the course of events linked to the (Second) Defenestration of Prague.

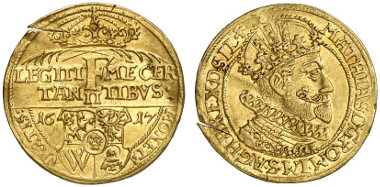

Breslau. Ducat 1617 on Archduke Ferdinand being crowned Bohemian king. From auction sale Künker 171 (2010), 5684.

When Ferdinand II, hitherto Duke of Styria, whom his family had designated as the next emperor, became King of Bohemia in June 1617, that country was still an elective monarchy. The Bohemian estates would have liked it very much to deny Ferdinand the election. He was a notorious Catholic and the Bohemians wanted nothing of the kind. In the native country of the reformer Huss there were only few Catholics at home. Protestants, Unitarians and Calvinists were in the majority. Thus, prior to the election, the Bohemians estates were desperately looking for a rival candidate for Ferdinand II. Count Palatine Fredrick V was being discussed but no workable coalition could be established for his election. John George I, Elector of Saxony and a moderate Protestant, had already declined with thanks.

The result was that Ferdinand, being the only candidate for the Bohemian crown, was elected – albeit on the condition that he guaranteed the Letter of Majesty from 1609 that granted the Protestants a number of privileges. The revenues a Bohemian king could yield from his country and the accompanying rule over Silesia, Lusatia and Moravia, were highly profitable. The tax yield from just this one province financed half of the administrative expenses of the entire empire of the western branch of the Habsburg family. Hence, it paid off that Ferdinand put his personal conviction aside in the time prior to his election.

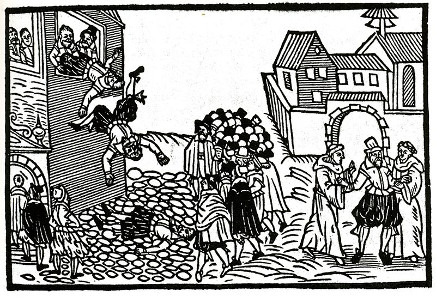

The (Second) Defenestration of Prague illustrated in a contemporary pamphlet, 1618. Source: Wikicommons.

The moment he was elected king, however, the problems began. The quarrel that led to the Defenestration of Prague was precipitated by the issue whether it had been right to build a Protestant church on royal territory or wrong since it was land the King of Bohemia had restored to the Catholic Church. Was the king allowed to give state land to the church at all? It was this question that infuriated some Protestant councilmen to such an extent that they stormed Hradcany Castle on 22nd May 1618, and threw two representatives of Ferdinand, Slavata and Martinez, and one comparatively innocent secretary in addition out of the window.

The estates of Bohemia and Moravia, 1619-1620. 12 kreuzer 1619. Kuttenberg Mint. Crown of St. Wenceslas. / Bohemian lion l. Herinek 18. From auction sale Gorny & Mosch 161 (2007), 5116.

Immediately after that act of violence, the rebels built a provisional government consisting of a directorate with ten representatives of each of the three estates as members. They agreed on forming an army. That was a wise decision because Ferdinand didn’t dream of abandoning the high revenues from Bohemia. He used Spanish money to finance an army that crossed the Bohemian border as early as August 1618. At this point, the Bohemians remembered Frederick V, Elector Palatine, who had been discussed as a possible election rival for Ferdinand II.

Portrait of Peter Ernst II von Mansfeld. Source: Wikicommons.

They asked him for help. On 28th August 1618, a second army of the Habsburg family left Vienna for Bohemia, and on 30th August 1618 the Bohemians formed an alliance with Frederick V. He provided them with an army that was commanded by Mansfeld, a leader of mercenary soldiers.

In the next episode you will read about the fight about Bohemia and the nerve-stretching imperial election that took place against this highly volatile political backdrop.

You can find all parts of our series here.