translated by Katja Protsiva

After Robert Guiscard has been accepted not only by the pope but also by the Norman aristocrats, the sixth son of a mediocre lord of a castle from the furthermost corner of Normandy ruled his own duchy.

Robert Guiscard. Tari d’oro, Palermo. From auction Künker 166 (2010), no. 3924 – The first Norman coins, minted in Sicily, were issued in the name of Robert Guiscard.

Thirst for land!

But that was still not enough for him. As the contemporary chronicler Gaufredus of Malaterra wrote: “Tancred’s sons had an insatiable lust for power by nature so that they could never calmly leave any of their neighbours in possession of land and people as far as their power permitted; every neighbour either was forced to work for them or they took everything they owned away from them.” Therefore, Robert decided to make use of what he was entitled to after the pope invested him duke of Sicily and to conquer the territories that were still under Muslim control. But it took about 30 years until the Hautevilles controlled whole Sicily.

There is a good reason why the conquest of Sicily took such a long time: the Normans almost preferred fighting against each other than against the heathens. However, Roger, who followed Robert Guiscard as ruler, was a man at his side who not only knew how to win militarily but also knew how to score with diplomatic moves.

Engraving of the city Messina by G. Braun & F. Hogenberg from the year 1572.

With the conquest of Messina in 1061, a bridgehead was established which facilitated yearly invasions of Arabic territories. Two years later, in 1063, Robert got the pope to approve the conquest of Sicily as a holy war – pretty much at the same time as the northern Spanish kings were conquesting Muslim territory with the help of knights, who were provided to them as fighters against the heathens by Cluny Abbey. The church developed the concept of the holy war during the 1060ies and Robert quickly learned how to use it to his advantage.

Roger in the battle of Cerami, 1063. Painting by Prosper Lafaye around 1860.

When it came to an important battle in June of 1063, Roger went into war for his brother. During battle, his knights saw a beautiful young man on a white horse in white armor holding the white bannerette with a red cross in his hand. The present believers cleverly figured that he must be Saint George, who was sent to them from heaven in order to support them in the fight against the heathens.

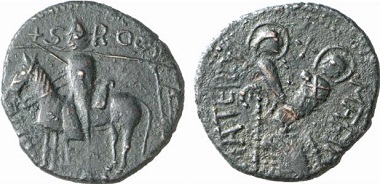

It is not Saint George here but Roger who goes into battle on a horse. Roger I. Trifollaro o. J., Mileto, 1072-1101. From auction Künker 137 (2008), no. 3789.

Roger immediately sent a delegation to inform the pope about the heavenly support. He added four camels as a gift and received a sanctified banner from Alexander II. As an addition, the pope announced that all those who would die in Sicily in a battle against the heathens would be immediately sinless. That was very appealing at a time when a life could surprisingly end at any moment. With the combination of the fight against the heathens, land appropriation and absolution, the church in Sicily and Spain developed a concept that would celebrate its greatest success with the call for the armed pilgrimage and the liberation of the Holy Sepulcher of Jerusalem in 1099.

Roger receives the keys of Palermo. Painting by Giuseppe Patania, 1830.

Tolerance as the foundation of conquest

In 1071, Robert took advantage of the Byzantine emperor’s defeat in Manzikert in order to conquer Bari, the last Byzantine base in Apulia. For this purpose, he arranged the first powerful fleet of Lower Italy Normans. He lent it to his brother Roger the year after that. That facilitated the conquest of Palermo.

With that, the Normans had two important bases for ruling Sicily: Palermo and Messina became the centers from where Roger slowly tied single princes to himself using violence and diplomacy. By then, he bore the title Count of Sicily and was subordinate to his brother Robert. Robert, as feudal lord, kept the most important territories, like Palermo, under his control. But since he could not rule Lower Italy and be on site in Sicily at the same time, Roger was able to expand his authority wide beyond the officially permitted region.

Roger I. Tari d’oro, o. J., Messina. From auction Künker 137 (2008), no. 3787.

The citizens of Sicily gladly supported him, because Roger offered a broad religious tolerance and the privilege to still be judged according to their own law. This policy became the basis for the incomparable thriving of the Sicilian empire. Obviously, the taxing was high – but equally divided among Moslems, Jews, orthodox and Roman Christians. If someone had a complaint they could phrase it in either of the four official languages: Arabic, Greek, Latin or Norman French. Administrative offices were mainly held by locals. When this was impossible, local important figures were compensated by receiving sufficient land in a region in Lower Italy where they had no allodium whatsoever.

The “Martorana” was donated by George of Antioch, the admiral of Roger’s son Roger II. The mosaic decoration indicates the orthodox religion of the donor. Even today, the Byzantine ritual of the Italian Albanians is celebrated here. Photo: KW.

The Moslems kept their mosques – they just had to give up the buildings that initially had been churches. Many of them became property of orthodox Christians who had found refuge in Sicily. Robert arranged for the establishment of Catholic faith on the mainland, whereas in Sicily, there were greater liberties in practical aspects of liturgy, although it was under the pope’s control. Roger secured the trust of his orthodox subjects by fostering their church projects to a great extent.

The active policy of tolerance that Roger promoted in Sicily not only accommodated his own preferences but also bore clear advantages: Roger recruited a Saracen elite troop from the Muslim population that faithfully served him. The fact, that their exercise of religion was linked to the mercy of the ruler, made them a loyal force that could easily be used against any Christian enemies and even the pope. Roger’s orthodox and Muslim subjects observed how Roman Christianity took over in neighboring Calabria and Apulia; no wonder that they were so content with their tolerant ruler.

In the next chapter, you can read how Robert Guiscard switched his focus from his duchy towards the east, the new target of his ambition: the Byzantine Empire.

Here, you find all the chapters of the series.

And if you want to see more pictures of Sicily, we recommend you our series “Sicily in full bloom”.