with the kind permission of the MoneyMuseum, Zurich

Why is it that for centuries – or rather thousands of years – the head has served as the motif for the side of a coin? And why has this changed in the last 200 years? In this chapter of the series ‘Human Faces,’ you’ll read about the purportedly ‘virtuous’ Marcus Aurelius.

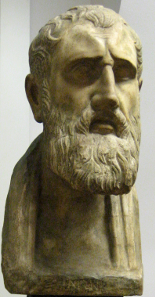

Roman Imperial Era. Marcus Aurelius (161-180). As, 177. Head of Marcus Aurelius with laurel wreath facing right. Rev. Ship, sailing to the right. © MoneyMuseum, Zurich.

When Hadrian adopted Antoninus Pius as his successor in the year 138, he also stipulated who was to follow Antoninus as emperor. The choice was made in favour of Marcus Aurelius, Antoninus’ eventual adoptive son, who was just 17 years old at the time.

For both successors, one thing was certain: they would never wage war of their own accord. This was Hadrian’s aim – he wanted to finally bring peace to the Roman Empire. But what the forward-looking man had overlooked was the fact that both of his successors lacked vigour and energy. Antoninus Pius was a bureaucrat, and he raised his adoptive son as a bureaucrat as well. Even at the time of his accession to the throne, Marcus Aurelius could still pride himself in the fact that he had never spent a single night outside his father’s house. And so, when the emperor acceded to the throne in the year 161, he lacked military experience of any kind, boasting instead a mastery of orating and knowledge of the teachings of all the philosophers. But this did not prove enough to defend his empire.

More specifically, the Parthians were threatening the borders. Rather than rushing to the front himself, Marcus Aurelius stayed in Rome and sent his desperately ill co-ruler, Lucius Verus, in his stead. It was only when Lucius was killed in another campaign against the Marcomanni that Marcus Aurelius was himself forced to assume supreme command. He did so begrudgingly. He would have much preferred to stay in his palace in Rome, philosophizing about a moderate life and virtues. Now he had to provide his services at the frontiers. He consoled himself by recording his travails in a book, ‘Self-Meditations,’ which oozed with self-pity, and by taking a daily nightcap into which his doctor had mixed plenty of opium.

The Stoics, the philosophical teachings of Zeno of Citium, reached its peak under Marcus Aurelius. This cast of a herma of Zeno from the National Museum of Naples is in the Pushkin Museum. Photo: shakko / http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

Apart from the opium abuse, he did with the teachings as many citizens had. The Stoics had captured peoples’ ways of thinking – they celebrated the acceptance of each and every situation, that sense of unwavering perseverance in duty, without joy and devoid of enthusiasm. As such, they could easily understand a figure like Marcus Aurelius. They all hated the hardships inflicted upon them by the resistance of the huge, advancing Migration Period tribes.

Even the Christian Church Fathers had adopted the stoic ideals and, in Marcus Aurelius, found much that corresponded with their ideal of worldly renunciation. And this is how the imperial diary, to which even today’s enthusiasts of Marcus Aurelius wouldn’t dare ascribe originality, survived. The renaissance took over the Church Fathers’ judgement, and made the underachiever on the imperial throne into the Christian model of an ideal ruler.

In the next chapter, you’ll learn how an emperor used coins to give thanks for his convalescence.

All sections of the series can be found here.

The book ‘MenschenGesichter’ is available in printed form from the Conzett Verlag website. It soon will be translated to English …