The first revolt of the Jews

It was under Nero’s reign that the Alexandrinian Jews truly revolted for the first time.

Nero, 54-68. Tetradrachm, 67/8. Rev. “Sebastophoros” ship sailing r. Münzhandlung Basel 6 (1936), 107.

The cause was rather unspectacular: when the Alexandrinians planned to send a delegation to the emperor, they invited all citizens to come to the amphitheater in order to pick the ones that should go. Some members of the Jewish community wanted to know what was going on exactly, so they snuck in and took a place amongst the Alexandrinians gathered there, although their legal status didn’t permit them to join the people’s assembly. They were discovered, arrested and sentenced by an infuriated mob. The punishment: death by burning alive.

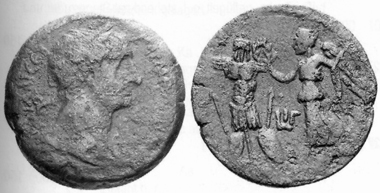

Galba, 68-69. Tetradrachm, 68. Rev. Kratesis in frontal view, standing with Nike and trophy. The name Kratesis stems from Greek “krateo” (=I rule). She was the deity that secured the Roman power over Egypt. That is why she was given a small Nike and a trophy as attributes. MMDe 12 (2003), 474.

It comes as no surprise that this harsh sentence fuelled the anger of the Jewish community. It erupted into an armed revolt that could only be defeated by two Roman legions marching into the Jewish quarter.

Love, money and an imperial throne

The wealthy upper class of Jews in Alexandria had successfully managed to stay out of these quarrels. But these circles were well aware that, from then on, precaution was of the essence.

In 68, a Roman army stood before Jerusalem and intended to conquer the city – the future of the exiled Jews was more than unsettled. Then Berenice arrived on the scene, sister of Herod Agrippa II and widow of one of the wealthiest men of Alexandria, the Jew Marcus Julius Alexander, and presented her former brother-in-law Tiberius Julius Alexander, who was Praefectus Aegypti at that time, an unexpected solution: since it was all haywire in Rome after Galba had been assassinated, why not bring a man to the throne who was considerate towards the Jews of Alexandria? And she had already thought of a fitting candidate: the father of her lover Titus, the old Syrian warhorse Titus Flavius Vespasianus. He could count on being supported by the Syrian governor and hence the three Syrian legions. Plus his own, stationed before Jerusalem – and the two Egyptian ones in addition…

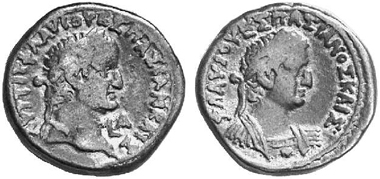

Vespasian, 69-79. Tetradrachm, 69. Rev. bust of Titus r. From auction sale 89 (2004), 1763.

Tiberius Julius Alexander shared the opinion of his former sister-in-law: on 1st July 69, he declared Vespasian emperor and ordered to stop all grain deliveries to Rome. After all, it was Egyptian grain that was used to pacify the Roman plebs. Why not make life a bit more difficult for Rome’s current leader?

In November 69, Vespasian traveled to Egypt himself. In the meantime, others conquered Rome for him, while he turned into a god in Alexandria. To do so, he had to pick an opportune moment.

Nile River. Satellite view of NASA.

Thus, Vespasian made sure that his arrival coincided with the beginning of the annual Nile flood. That made it easy for the future emperor to be celebrated as bringer of fertility.

Nilometer. Mosaic floor from the House of Leontis, Beth Shean, 6th cent. A. D. Israel Museum. Photograph: UK.

As a matter of fact, Vespasian allegedly caused the Nile to rise for an entire palm which was something unheard-of so far, taken by eulogists as testimony to the special divine grace. Oracles and wonders were on next. But let us hear what Suetonius has to say about that (Vesp. 7): “There he dismissed all his attendants and entered the temple of Serapis alone, to consult the auspices as to the duration of his power. And when after many propitiatory offerings to the god he at length turned about, it seemed to him that his freedman Basilides offered him sacred boughs, garlands, and loaves, as is the custom there; and yet he knew well that no one had let him in, and that for some time he had been hardly able to walk by reason of rheumatism, and was besides far away.”

Bust of Vespasian. Plaster cast at the Pushkin Museum, St. Petersburg, after an original in the Louvre. Photograph: shakko / http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.de

The oracle was obtained, and the only thing still missing was the wonder: “Vespasian as yet lacked prestige and a certain divinity (…), but these also were given him. A man of the people who was blind, and another who was lame, came to him together as he sat on the tribunal, begging for the help for their disorders which Serapis had promised in a dream; for the god declared that Vespasian would restore the eyes, if he would spit upon them, and give strength to the leg, if he would deign to touch it with his heel. Though he had hardly any faith that this could possibly succeed, and therefore shrank even from making the attempt, he was at last prevailed upon by his friends and tried both things in public before a large crowd; and with success.” It is highly likely that the Egyptian priests knew quite well how to prepare such a wonder. The emperor only had to show up in the hippodrome where speaking choirs praised him as new ruler.

Giulio Romano (1499-1546), Triumph of Vespasian and Titus. Oil, Louvre, Paris. Source: Wikipedia.

In the middle of August, Vespasian traveled from Egypt to Rome. There, the grain carriers that were arriving in time again at last, ingratiated him with the crowds. Vespasian’s son Titus arrived even later than his father. After all, he not only had to conquer Jerusalem first, but to present himself as official successor to the people of Alexandria (and – perhaps even more important – to his financiers). After having done that, he went to Rome to celebrate the triumph together with his father. Both spent the night before in the local Temple of Isis. We may well consider that a token of gratitude towards Egypt.

The Great Jewish Revolt in Alexandria

In the aftermath of the first Jewish-Roman war, many extremists were forced to exile. The had to look for a new home and some kind of protection thanks to a certain degree of anonymity and the possibility to continue their fight in addition. Naturally, Alexandria was a place more than suited for that. Hence, the elders of the Jewish community there were faced with the problem that, again, some of their members called for war. That was the last thing the rich Jews had had in mind when they had supported the imperial family of the Flavians. They wanted peace with Rome. And so the Jewish council of elders actively opposed the upheaval by personally arresting the worst of the agitators. Many extremists however managed to escape to Upper Egypt where they made preparations for the war against Rome.

Trajan, 98-117. AE, 109/110. Rev. Nike with palm branch, crowning a trophy. MMDe 14 (2004), 766.

They sniffed their chance when Trajan pulled out one of the two legions stationed in Egypt for the Parthian war. In the beginning, the upheavals were still small and localized, but soon the whole of Egypt was in an exceptional state. Alexandria witnessed the largest-ever civil war. At first it was the Jews who prevailed – they looted and destroyed Greek and Egyptian temples. But their triumph was transient.

Trajan, 98-117. AE, 109/110. Rev. triumphal arch. MMDe 14 (2004), 765.

It took only a short time for the Roman military to get the situation under control again. The victims were not the homeless partisans but the Jewish civilians whose children were beaten to death and whose possessions were seized. The few survivors were forced to leave their home town Alexandria and to settle down beyond the city boundary in a new district. The power of the Jewish community, both in terms of economy and politics, was broken. They seized to be an important factor in Egyptian history.

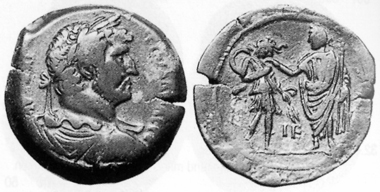

Hadrian, 117-138. AE, 130/1. Rev. emperor giving Egypt a leg-up. CNG 13 (1990), 112. The reverse motifs of 130/1 focus entirely on the imperial visit. In the following year, the mint reverted to its usual subjects for the coin reverses again.

Hadrian visits Egypt

Hadrian visited Egypt in 130/1. He and his entourage arrived at Alexandria on 13th August 130.

Hadrian, 117-138. AE, 130/1. Rev. ship sailing l. with emperor wearing military suit and elevated right. CNG 13 (1990), 514.

There, he was able to dispute with the scholars of the Museion to his heart’s content, chase lions in the Libyan desert, and act as building commissioner. In October, the emperor embarked on his ill-omened Nile cruise. It is one of the most often told imperial voyages because on the way beautiful Antinoos, a member of the imperial entourage, met his death in the nome of Hermopolis.

Antinoos, + 130. AE, 134/5. Rev. Antinoos riding r. CNG 13 (1990), 80.

Scholars are still not entirely certain who this Antinoos was exactly. We only know that he had been born sometimes between A. D. 111 and 115 in Bithynion-Klaudiopolis / Bithynia, that he was gorgeous and enchanted emperor Hadrian when he traveled through the youth’s native country. From then on, Antinoos accompanied the emperor.

Statue of Antinoos. National Archaeological Museum of Naples. Photograph: UK.

It is conceivable that, by its love towards Antinoos, emperor Hadrian intended to follow the ancient Greek educational ideal of a mature man guiding and training a noble youth, both spiritually and physically. Be that as it may, Hadrian was inconsolable when he learned about his friend being fallen into the Nile and drowned during the night of 30th to 31st October 130. The course of this tragic event is a matter of dispute until the present day. Had political begrudgers pushed the young man into the water? Had Antinoos committed suicide since, in all his beauty, he felt the imperial interest diminish? The most romantic version tells of a self-sacrifice Antinoos had committed in order to add his own life years to the ones of the emperor.

Coins are witnesses of the life and the death of Antinoos, as well as relatively many statues Hadrian had ordered to produce. Their mysterious, dreamy beauty continues to fascinate esthetes throughout the world. Hadrian was not granted to mourn for long. The logistics required for supplying his 5,000 or so companions forced him to proceed on his journey after just a few days, first to Thebes, then via Oxyrhynchos and Tebtynis back to Alexandria and from then on to Syria.

The next episode introduces you to the intriguing coinage with astrological-astronomical background which Antoninus Pius used for his own purposes cleverly, and to the difficult situation at the end of the 2nd century.

You can find the other parts of this series here.

Together with Thomas Ganschow, Ursula Kampmann has written a catalog on the Alexandrinian coins. For ordering it, please click here.