The People of Zurich and their Money 11: Ziegler – the soldier millionaire, who would not know him?

by courtesy of MoneyMuseum

Our series “The People of Zurich and their Money” takes you along for the ride as we explore the Zurich of times past. Leonhard Ziegler, after going bankrupt, fled to India in 1802 to become one of the country’s richest men – he advised his fellow countrymen to follow his example, to learn English and go abroad. Much like a good DVD, this conversation comes with a sort of “making of” – a little numismatic-historical backdrop to underscore and illustrate this conversation.

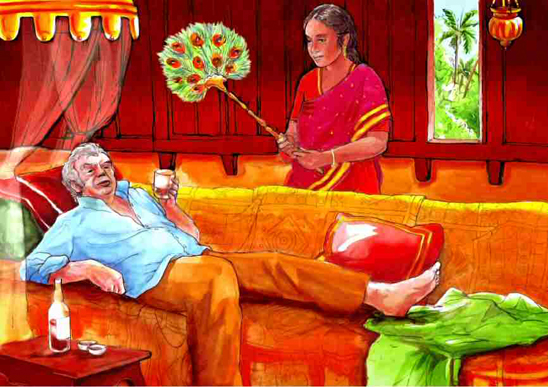

India 1826. Leonhard Ziegler talks to his native maid at his farm. Drawn by Dani Pelagatti / Atelier bunterhund. Copyright MoneyMuseum Zurich.

Ziegler: (all excited) I did it, Naikan! I did it. Finally all my debt is paid. I could return to Zurich now. Nobody would have believed that this could happen, when I left Zurich nearly 25 years ago, after going bankrupt.

Maid: (timid) Yes, Ziegler Sahib.

You should have seen me then, how I arrived in India. I was a private soldier. But I worked my way up. I learned all these languages. So I became indispensable. You know, they hate to learn languages, these Englishmen. Otherwise a damned clever people! They send their sons to the colonies in order to give them the chance to make a fortune. Half the men perish, half the men make it and bring back the wealth to good old England. Damned clever! (proud) And I did the same.

Yes, Ziegler Sahib.

I took my chances. I realized immediately that it was a unique opportunity, when Major Grace introduced me to his friend Bond. He had an indigo plantation and he needed somebody to control it. I was the right man. And he paid 100 rupees a month. Damn it, that was a lot of money! Being soldier I earned 40 rupees only.

Yes, Ziegler Sahib.

Oh yes, those were the days. I nearly died of homesickness. Nevertheless, do you know what I did, when my relatives sent me 50 Louis d’or paying for my return?

No, Ziegler Sahib.

I returned the money. I wrote that I wouldn’t come! Leonhard doesn’t return empty-handed! And that’s that. Then I worked like a dog. First for Mr. Bond, and after he died for Mr. Wyatt. And when Mr. Wyatt had to sell to the banker in Calcutta, I got a new chance. Mr. Colvins appointed me sole manager of the plantation. He paid 350 rupees a month! And he granted me a participation in profits.

Yes, Ziegler Sahib.

And I paid off the creditors with this money. I paid back 27.824 gulden and 20 shillings, exactly half of my dept of 55.649 gulden. I sent a cheque of 2.000 pounds to Zurich. That was too much, but my brother’s having a filthy time, he’ll take the rest for his needs.

(imploring) Please, Ziegler Sahib, what about my child? And what about me?

Shut up! I’ve taken enough care of you.

Indigofera tinctoria. It is this indigo plant Ziegler owed his financial recovery to. Photograph: Kurt Stüber / Wikipedia.

Making of:

The story of Leonhard Ziegler (*1770, †1846) takes us right into a period of time when the merchants and manufacturers from Zurich began to take a look beyond Europe and do lucrative business in the colonies. Ziegler was a pioneer who constantly advised the fathers of Zurich to let their sons learn English to enable them to make their fortune in the countries of the English dominion. And indeed, many Swiss companies probed the new overseas market and did good business on distant continents.

Leonhard was the younger son of Jakob Christoph Ziegler, a man of private means. Whereas his brother launched a military career, 19-year-old Leonhard established a trading company for muslin in 1789. After some initial success the young man enmeshed himself in risky affairs with the government. The French had abolished the old Swiss city states in favor of a central government. Ziegler traded Austrian state bonds on their behalf which, however, Vienna refused to acknowledge since they used to be part of the confiscated Bern treasury. This plunged Ziegler into ruin. According to a list of creditors dating back to 1824, he left debts amounting to 55,649 gulden. At first glance, this seems a huge sum – after all, the daily wages of a Zurich carpenter, at the rank of a foreman, was roughly one gulden between 1790 and 1800 –, but, as a matter of fact, this bankruptcy ranged in the lower regions. The amount of debt of other bankrupt companies since the middle of the 18th century often read something between 100,000 and 800,000 gulden per company.

Leonhard Ziegler was forced to leave Zurich, and his wife filed for divorce. By that, all connections with home were cut for the 32-year-old for the time being. Ziegler decided to bend his steps towards India and try to take his chance there. Actually, getting to India was generally difficult because the East India Company strictly prohibited any civilian from entering the subcontinent. Leonhard Ziegler achieved his aim by signing on for the East India Company as serviceman. As a private soldier, Ziegler arrived at India in 1803. Thanks to his language skills, however, he managed to work his way up. He won himself the support of the influential Major Grace who placed him with an indigo planter.

After the opium which the East India Company had the monopoly on, indigo was India’s second most important good. European ‘farmers’ gained it by buying or renting land that was already used and cultivated by local peasants. These men were forced to dedicate a part of their land to the indigo production. They had to buy the indigo seed at a price the principal had fixed and they also had to sell the harvest at a likewise determined price. Since only the orderers kept account, a clever administrator could easily increase the profit of his employer by invoicing for his benefit.

Leonhard Ziegler became a “dschuta saab”, i.e. the person responsible for liaising between the British planters and the local people. When inspecting the indigo plantations he made use of the riding whip against the locals more than once. Although this behavior seems morally despicable to the modern viewer, Ziegler was considered a superb administrator because he not only spoke the national language fluently but he was willing to do the hardest work.

Ziegler believed that his new position would enable him to finally make enough money to pay off all his creditors and return to Zurich rehabilitated. Hence, he didn’t want to accept alms anymore even when they came from friends. In December 1806, he sent back a draft of 50 new louis d’or and refused to return to Zurich with the following words: “Being patient, if it is convenient, and take this as my ultimatum for the time being: Leonhard doesn’t come home empty-handed, and that’s that.”

In 1808, Leonhard Ziegler changed to another plantation that was run by a Mr. Wyatt. His financial situation seems to have become fortunate by that time so that he managed to send his brother, who was in economic trouble, 1,000 rupees per year on a regular basis.

British East Indian Company. Rupee, after 1803, Arkat. Overstruck on an 8 reales piece from Peru from 1803. Künker 131 (2007), 4466.

When Wyatt was forced to consign his land for 150,000 rupees to a banker in Calcutta in 1815, Ziegler’s moment had finally come. He became sole administrator of the plantation and received for his work not only a monthly salary of 350 rupees but an annual profit sharing in the amount of one third of the total yield. Three good crops in a row made Ziegler enough cash and enabled him to start clearing debts in 1818. In 1824, he offered his creditors to repay half of his total debts, amounting to 55,649 gulden, on the condition that they, in turn, waived all further claims. His creditors agreed on these terms in 1826 and in that very year Ziegler wrote out a check for 2,000 English pounds. This check most likely was the biggest the citizens of Zurich had ever caught sight of.

East Indian Company. 1/3 mohour (5 rupees), n. y. (1820), Bombay. Künker 207 (2012), 6616.

After having repaid his debts, Ziegler’s assets in India still added up to the proud sum of 100,000 rupees in cash. Plus, he had paid the same price for the plantation of Wyatt. And there was more to come. Ziegler became known as “the soldier millionaire”, much to the pleasure of his Zurich relatives which received subsidies between 100 and 400 English pounds every year from him.

The Zurich folk only were startled when they learned in a roundabout way that Leonhard Ziegler had conceived a daughter in India. This girl most probably was the result of an affair with a local woman. That was a common habit in those days and considered insignificant by the colonial masters. The family, which seriously feared for the inheritance, was assured by Leonhard Ziegler that he had no intention whatsoever to accept that girl, which he had ‘adopted’, as rightful heir. He only planned to pay for her education and her outfit but that was it.

On December 18, 1846, Leonhard Ziegler died in Seetulpore, being one of the richest men in all of India.

In the next episode we will return to Zurich and hear the response to an outrageous announcement: the city walls of Zurich will be battered down!

You can find all other parts of the series here.

The texts and graphics come from the brochure of the exhibition of the same name in the MoneyMuseum, Zurich. Excerpts with sound are available as video here.