by Ursula Kampmann

May 9, 2013 – There are still paradises left on this earth – and the small port of Assos in Troas is one of them. Join us on our excursions through Troas, as we explore Troy, but first, as we marvel at the extremely finely preserved Assos.

Sunday April 21, 2013

In the morning, we made a hasty departure from the rather inhospitable Erdek. Several huge tour groups had obviously made it to the breakfast buffet before us, leaving behind a bare, yawning chasm. Somewhat dismayed, we feverishly scanned our guidebook for alternatives to our planned itinerary. One thing was clear: Our initial plan of looking for the excavations in the interior on the way to Lycia had been theoretical at best. In reality, too many hotels were still closed. We would have to stop at the larger tourist centres in order to find somewhere to stay. But where exactly was there a big enough tourist centre in the north? We decided to look for it in Assos, where the guidebook had promised a few quality hotels. Since tour groups traditionally stop there, there was a good chance that the hotels would be open. It was probably the first time I was downright grateful to Studiosus & Co! (a Munich tour operator).

We were in a hurry to get to Assos, and slow driving has never really been Kurt’s thing anyway. We’d barely been on the road for half an hour when a friendly man in uniform waved us out of the traffic. According to him, after adjusting for tolerance, we had been going 133 km/hour in a 90 km zone. I’m afraid he was right too. Good thing that speeding penalties in Turkey aren’t quite as draconian as the ones at home.

It’s quite amazing really just how many things can be done practically without even being able to speak each other’s language! We dutifully filled out the required form, and the policeman was pleased that we already knew how to say ‘evet’ (=yes) and ‘tamam’ (=agree). It was a lovely, peaceful exchange, although this didn’t change the fact that we still had to pay our fine. As did, incidentally, another slightly overzealous driver from Istanbul who had also been waved out of the traffic. (So much for the preconception that only tourists have to pay up. Quite the opposite, actually. With a large volume of traffic controls, the Turkish police are always busy trying to constrain Turkish drivers’ creative interpretation of the road traffic act.)

At the end of the whole procedure was a little surprise: In Turkey, you get a discount for early payment of the fine. Because we handed over the money immediately, we only had to pay 125 Turkish liras instead of 160. And it was all very official. We were given a giant receipt from the receipt book. The fact that the policeman got us our change for the fine from that recently caught speeder from Istanbul is a testimony to just how lax things are in Turkey.

Through scenic countryside. Photo: KW.

We drove on, dutifully abiding by the official road traffic act. And in all honesty, the route was so beautiful that it would have been a shame to pass through it too quickly. The best way to reach Assos is by a road that leads away from the coast over steep passes and towards the interior. Once again it becomes clear that for the Greeks, roads inland weren’t important, since they could get from port to port faster by boat.

A little bit of paradise: Assos harbour. Photo: KW.

We arrived in the tiny port of Assos by way of an adventurous potholed road. There are no locals here anymore – that is, unless, they run a restaurant, hotel or guesthouse. Nevertheless, the harbour is truly idyllic. The old storehouses dating back to the Ottoman era have been converted into hotels. We decided on the Nazlihan Otel – and were given a lovely room on the first floor with a balcony that had a direct view of the harbour and from which you could look out at the island of Lesbos, which lies opposite.

And so, we marvelled from above at all the people from Istanbul who were spending their Sunday in Assos. They had filled all the fish restaurants on the harbour, so we decided to look for a place in the second row. But they were also packed with people. We waited almost 45 minutes before we even got something to drink. Before the food was actually in front of us, we had pretty much lost all hope of ever getting anything. But the appetizers and the kofta, all served at the same time, were so fantastic that we quickly forgot our long wait.

I spent the rest of the evening trying to navigate the pitfalls of Turkish Internet and WLAN. Unlike Greece, Internet use here still really just depends on luck. Yes, in theory all the rooms were equipped with Wi-Fi. In reality, however, there were three different networks in the hotel, all of which alternated in terms of which one worked. And then you also had to find out from which point in the room you could actually access it … And so, this numismatic diary is the result of somewhat difficult circumstances!

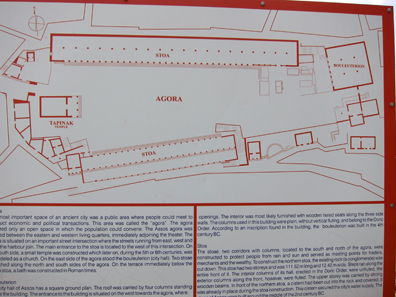

Layout of the archaeological excavation of Assos. Photo: KW.

Monday April 22, 2013

Have you heard much about Assos? I’ll admit, I knew that the city existed – after all, it had coins minted – but that’s as far as my knowledge went. We were surprised to find that there’s a huge excavation here that extends across a large part of the city area.

We stopped at a parking lot that wasn’t quite ready yet for the summer season – there were still piles of sand sitting where someday, large numbers of cars were supposed to park. This didn’t really pose a problem though, since apart from the odd tourist bus, there was only one other non-local car there.

Assos (Troas). Hemiobol, ca. 5th century BC. Initial publication and assignment to Assos provenance at Gorny & Mosch 204 (2012), 1471.

Assos is said to have been founded in the 7th century by colonists from Methymna, on Lesbos. Which is not really surprising – Lesbos is so close that you’d like to believe you could just swim across. In the middle of the 6th century, Assos came under Lydian control, and with that, following the conquest of Sardis in 547, became a part of the Persian Empire. Like most cities of the Troas, after its liberation in the wake of the Persian defeat in 480/79, it became a member of the Delian League and remained so until the year 401. The city paid an annual 1,000 drachms to the federal treasury. It was only the Peace of Antalcidas, from 387, that robbed Assos of its independence and returned it to Persian rule – against the will of the people. As a result, in 366/5, the people of Assos backed the revolt of Eubulus, a rich banker, who had allied himself with the satraps Ariobarzanes.

Assos (Troas). Obol, 475-450. From Münzen und Medaillen 36 (2012), 360.

Eubulus seems to have been an interesting person. He sent his favourite slave, Hermeias, to Athens to study philosophy. Upon his return, the former slave advised his master Eubulus on all government business and even assumed the reign following his death. The tourist office of Assos still uses this bit of information today, since Hermeias extended an invitation to Aristotle in 347 BC and then married him to his charge. And so, it’s not a statue of Eubulus or Hermeias that stands at the entrance to Assos, but rather one of Aristotle. Aristotle, however, could not prevent his father-in-law’s tragic death. Hermeias was captured during a visit of Memnon of Rhodes and delivered to the Persians, who had him executed at a time unknown to us. (Of course, once Aristotle could no longer rely on the support of his friend, he also disappeared from Assos.)

Assos (Troas). Tetrobol, 4th century BC. Künker 153 (2009), 8307.

Although Assos was briefly under Pergamenian rule, the city came under Roman influence after Attalus had bequeathed his empire to the senate. Assos benefited from the Roman peace. Trade flourished, and inscriptions tell of numerous inhabitants with Roman citizenship, who, for their own fame, donated all sorts of beautiful monuments to the city. Economic decline started at the beginning of the 3rd century, but all the same, the city remained a bishop’s see until the 5th century. It can no longer be pinpointed when exactly Assos went from Byzantine to Ottoman rule, but the changeover is likely to have been completed in the 14th century. After all, the city boasts one of the oldest mosques in Asia Minor, built under Murat I. (1326-1389). The majority of the Christian population at the time is said to have fled to Lesbos and as a result, the city sank into insignificance (inasmuch as it had prior significance).

The impressive city walls of Assos. Photo: KW.

The first thing that catches visitors’ eyes are the impressive city walls, which stretch along the area over a length of about 3 kilometres. From the 4th century BC all the way to the Byzantine era they were constantly rebuilt and reinforced with additional towers.

Reconstruction of the Temple of Athena in Assos. Photo: KW.

For all those interested in the history of style – the temple built in honour of Athena around 540/530 is the only Ionic order archaic temple in Asia Minor.

The remains of the Temple of Assos. Photo: KW.

Most present-day visitors use the temple more as a backdrop for their photos. It wasn’t easy waiting for that one moment when there was finally no one being photographed in front of, on or next to a column. From the highest point of the Acropolis – 236 metres above sea level, incidentally – you could see other architectural remains that we of course really wanted to see. There was a route indicated in our guide that we bought in Assos, so we tried to find it. And we ended up – and I don’t just mean this metaphorically – surrounded by sh**…! The trail was so steep that it was only suited to wild dogs and goats, whose ‘remains’ were lying around in vast quantities. And then, the path vanished into thin air! Eventually we found another route in that we scrambled over a trampled fence – apparently we weren’t the only ones to have gotten lost here – into a farmstead.

View of the Acropolis along the arterial road. Photo: KW.

It would have been somewhat more convenient had we just gone through a second gate, which was tied more symbolically with a green rope, into the deeper lying excavation site. There, a street lined with tombs led through the western gate to the next level.

Plan of the Agora. Photo: KW.

Here, we saw an agora of impressive size. It was about 150 metres between the small temple at the entrance and …

Bouleuterion. Photo: KW.

… the Bouleuterion, in which the City Council of Assos, the boulé, took counsel and kept the city’s most important documents.

The theatre of Assos in a gorgeous location. Photo: KW.

The lowermost entrance led to the theatre of Assos, with its gorgeous location and a view all the way to Lesbos. Although, only a few got to enjoy it. It would seem that the show ‘Pop Idol’ also has Turkey in its clutches – all the young girls seem to want to be stars, showing off their star poses for their audience. We watched four teens trying to have their pictures taken by their dragged along companions as they all jumped in the air at the same time and pulled their feet up towards their backsides. The spectacle was better than any cheesy early evening comedy. Still, I would have preferred listening to the crickets a little than to the military commands that accompanied the jump and the ensuing photo …

A new Trojan horse to deceive tourists? Photo: KW.

Tuesday April 23, 2013

We devoted this day to the city that gives Troas its name, the legendary Troy, or Ilium, or whatever the case may be, since academia seems only to agree on one thing, namely that their dear colleagues’ reasons why Hisarlik is Troy – or isn’t – are completely preposterous and definitely aren’t to be taken seriously.

Let’s say it loud and clear: For the marketing of the archaeological site, it’s useful if the great epic poem of the Wrath of Achilles can be located here. Consequently, Manfred Korfmann, the late leader of the excavation of the German Archaeological Institute, could not afford to have any doubt cast on the identification of Troy. Quite the contrary – every argument in favour of it secured him the favour of the Turkish authorities. As a result, the title of the site guide written by him is programmatically titled ‘Troy / Wilusa,’ with the latter term taken from Hittite sources. The intention of this is to establish a sort of historicity of the Trojan War in the philological realm as well.

If you read other academics’ books on the subject, you’ll be astounded at the amount of anger and malice with which the Troy-topic is currently being debated.

Ilium (Troas). Autonom, Flavian Era. Semis. Aeneas flees with his father, Anchises, and his son, Ascanius from burning Troy. From Gorny & Mosch 147 (2006), 1834.

We’re far removed, of course, from the Roman naiveté with which various emperors granted the city of Ilium one privilege after another, simply because they felt connected to ‘the old country’. Still, despite the call of scientific integrity, modern scholars should be wary of fully demystifying Troy. After all, who wants to have to deal with the complicated sequence of stratigraphy if they can’t at least toy with the questions of where, perhaps, Hector took his leave of Andromache and Helena flirted with Paris?

Ilium (Troas). Tetradrachm, 188-133. From Gorny & Mosch 164 (2008), 178.

Moreover, one has to accept that for Alexander of Macedonia or Augustus, the Iliad took place in Ilium. Just the reverence for the ancient descendants alone makes Troy something special, and nothing archaeological will change that, no matter how beautifully the layers of Troy are divided up.

Megaron. Troy II/III – 2300-2200 BC. Photo: KW.

To be quite honest, what tourist would want to spend hours trying to figure out which structure belongs to which layer? Although, Tübingen scientists have quite commendably managed – on metal sheet sponsored by Mercedes – to break down the complexity of Troy’s chronology a little bit, such that even average the average Joe visitor might have a chance of understanding how the city developed from a small hub into a major city. A large portion of the excavation was actually closed, since everything is being readied for the swarm of summer tourists; but what we did manage to see seemed logical, interesting, and understandable. Currently, the first station is a city wall made of mud-brick and a megaron with vaulted protective cover, dating back to the early Bronze Age.

Wild animals always find a way to use everything when humans don’t interfere. Photo: KW.

I particularly liked the wild bees that had used the holes in the bricks to build their nests, with no respect whatsoever for the Early Bronze Age!

South ramp from Troy II. Photo: KW.

Particularly impressive was the reconstructed cobbled way up to the southwest gate of the city wall. Schliemann considers this layer as the legendary Troy, and when he discovered a hoard next to the ramp, he programmatically called it the Treasure of Priam.

Palace house from Troy VI. Photo: KW.

Right next to the ramp, the ground plan of a palace house dated to the Troy VI phase, so from 1740 to 1190 BC, was discovered. This is the phase that excavators would like to link with the Wilusa mentioned in Hittite sources.

Lower city of Wilusa. Photo: KW.

For this phase, it’s not just the magnificent palaces that are known, but also the houses of the so-called ‘lower city’ where the ‘simple’ folk lived.

The spring grotto, the starting point of the irrigation system. Photo: KW.

As early as around 1000 years prior to the Troy VI phase, there existed the spring grottos and the irrigation system. This also likely slipped in to the already mentioned Hittite treaty. The water main could also be described as an ‘underground path / route,’ translated in Hittite as ‘KASKAL.KUR.’ And it’s precisely this word that is used for one of the gods of oath on the side of Wilusa in a 1280 treaty between King Alaksandu of Wilusa and the Hittite ruler Muwatalli II.

The holy area, dating Troy VIII. Photo: KW.

But let’s head back to safe terrain … This holy area has been dated to around 700 BC. Major renovations were carried out in Hellenistic times, and were certainly initiated due to the visit of Alexander the Great, who made a political issue out of Troy. He had to support the city. Ultimately, as a new Achilles, he would destroy the Persian Empire, as the Greeks once destroyed Troy under Agamemnon. In 85 BC, Fimbria, a supporter of Marius and thus, an opponent of Sulla, destroyed Troy. The temple area was also severely damaged and was only renovated again under Augustus.

The Odeion of Troy. Photo: KW.

The excavators of Troy would also like to link the Odeion with Augustus: ‘The discovery of an Augustus head suggests that the Odeion was erected to mark his visit in 20 BCE, and that possibly the Aeneid, the eulogy to his mythical past, was brought to his attention here for the first time. Virgil, after all, left behind a still unfinished work and died in 19 BCE.’ Well, is it possible that Augustus really heard the epic poem here for the first time?

The true stars of Troy. Photo: KW.

Receiving considerably more attention than any of the rocks from either Troy II, VI or VIII were a couple of fuzzy, young dogs that not even the Turks managed to shoo away.

And that was it. We drove back to our hotel. Join us for the next episode as we head to Troas’ most important city during the Roman Imperial Era, to Alexandria Troas, as well as to the temple of Apollo Smintheus, the Mouse God.

All parts of the series ‘Springtime in Turkey’ can be found here.