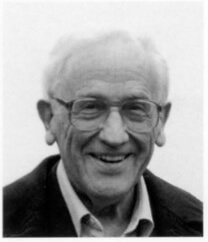

On 24 November 2019, Franz Füeg died. He is probably known to anyone interested in Byzantine numismatics as the publisher of two die corpora for the periods 713–976 and 976–1067. However, only a few coin collectors are aware that – in “real life” – this great systematist was one of the most distinguished architects of Switzerland.

A Die Corpus

I got to know Franz Füeg about 20 years ago. Back then, I was working as secretary of the IAPN’s Anti Forgery Committee and faced the problem of initiating investigations into the authenticity of a coin of Basil I. The leading experts of Byzantine numismatics were unable to agree on the matter. Somebody gave me the tip to contact a retired private researcher who had dedicated himself to cataloguing the coin dies of this period. I called him, sent him the piece and, less than two days later, I received his answer: He said, the specimen was a dangerous transfer die forgery. He stated that the “mother piece” was published here and that a number of those forgeries produced by a die modelled from the “mother piece” were published there, there and there. Professor Füeg dutifully filled in the expert form, and the problem was solved. Nobody, absolutely nobody was able to contradict the few sentences he had written, which contained one of the most conclusive argumentations I have ever read.

At that time, I didn’t spend a second thinking about whether the humble man – with whom I spoke many times via phone on the subject of questionable coins in the course of the following years – was more than a pensioner enjoying his spare time by making a catalogue of Byzantine coinage.

One of the Most Important Architects of Switzerland

Franz Füeg was born in Solothurn on 31 October 1921. His father had a workshop for artistic carpentry. His son completed an apprenticeship as a draughtsman in structural engineering in his hometown and found his first job with Hans Bracher, who went down in architectural history as the pioneer of the “Solothurn School”, a movement of Swiss architects including Franz Füeg.

He left Switzerland after the Second World War. He went to Rotterdam, which had been levelled to the ground by the bombing of the German Luftwaffe on 14 May 1940. For two years, Füeg worked in a major architecture firm that was involved in the reconstruction of the destroyed city. This experience had a lasting effect on him. In Rotterdam, he moved up to become chief architect and, a few years after returning to Switzerland, he founded his own architecture firm, which soon became very successful and was responsible for many buildings of the post-war era. From 1971 until his retirement in 1987, Franz Füeg was also Professor of Architecture at EPF Lausanne. In 2006, ETH Zurich awarded him an honorary doctorate.

St. Pius Church in Meggen

Füeg’s most important architectural work it the Catholic St. Pius church (Piuskirche) in Meggen, an austere cube whose outer appearance looks like a modern fortress at daylight. But whoever enters the building is surprised by the warm, golden light that gently embraces the visitors. This effect is achieved by translucent slabs of Greek marble that filter the daylight that enters the church. As daylight fades, the building goes through an incredible transformation: the light from inside the church shines through the marble slabs to the outside and makes the church become a glowing shrine illuminating the night.

Regardless of its young age, the building is listed as a cultural object of national importance in the Federal Registry for cultural property.

Critical, Analytical, Humble

Those who have already set foot in the church of Meggen have a small idea of the incredible imagination Franz Füeg must have had. With no understanding of frills and superfluous features, he focused on the structures – whether it be in architecture or in numismatics. In his die corpora, he limited himself just as much to the essential features as he did regarding his buildings. They do not contain superfluous words, just like it is the case with the book “Wohltaten der Zeit und andere Essays über Architektur und die Arbeit des Architekten” (Benefits of the time and other essays on architecture and the work of an architect) published by Füeg in 1982.

The focus is always on the subject matter. The creator disappears behind the project. Franz Füeg rarely spoke about himself. He was humble. Always polite. If you did him a favour – however small it was – he would always call you in order to thank you for it.

The Prix Duchalais

Although the numismatic world was only a “side stage” for Franz Füeg, his publications, whether it be an essay or a monograph, are paradigms of conclusive reasoning and profound knowledge. Thus, it does not come as a surprise that he was awarded the Prix Duchalais by the honourable Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres in Paris for his “Corpus of the Nomismata from Anastasius II to John I in Constantinople” published in 2010. He deserves it, even though this honour is outshined by all the honours Franz Füeg was awarded with as an architect.

Franz Füeg is a great example of all the wonderful people attracted by numismatics. We grieve with his family and mourn the loss of a man who accomplished so many things and yet remained so humble that, in the world of numismatics, only a few people know that his ideas of buildings shaped the Swiss cities of the post-war era.

On the other hand, the Wikipedia article (in German) shows Franz Füeg only as an architect and does not even mention his great passion for and dedication to numismatics.