June 25, 2015 – The British Museum hosts a display on medals of the ‘Sun King’ Louis XIV in its Room 69a until 15 November 2015. ‘Triumph and disaster: medals of the Sun King’, guest-curated by Mark Jones in the tercentenary year of the death of Louis XIV, explores the ‘Medallic History’ of Louis’ reign. Drawn from the British Museum’s own collection, which preserves these medals as they were in Louis XIV’s own day, from the British Library which has a unique manuscript scrapbook of drawings and notes on the creation of the history, and the V&A, this exhibition investigates the ideology behind this great commemorative project.

Nec Pluribus Impar. Designed by Jean Warin, 1672. Louis XIV as the sun warming the earth and the inscription means ‘not unequal to many’ which was his motto. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The greatest writers (including Jean Racine), historians, artists and medallists of the day were brought together by the king to ensure that posterity would see his rule as Louis wished it to be seen: the reign of an ideal and ever victorious monarch, a Sun King whose benevolent rays warmed and illuminated the whole world.

Hard Work. Designed by Renaudot, 1661. Louis is represented as Apollo, driving the chariot of the sun which brings light to every part of the earth. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

At the start of Louis’ reign he was young and handsome; and France was prosperous in peace and victorious in war. These early medals portray a dazzling image of a ‘Sun King,’ who is represented as hard-working, accessible, generous and just; a king that worked for the benefit of the people, glorifying as much in their happiness as in victory over his enemies.

The picture changed as war succeeded war and defeat succeeded victory. The later medals, though careful to represent only French successes, are so numerous that they give the impression not of victory but of endless and draining warfare.

Colossus of Rhodes, 1709. Louis is shown as the Colossus of Rhodes crumbling under its own weight. The medal celebrates the capture of Hainault from the French in 1709 and is representative of the widespread feeling that Louis’ pre-eminence was coming to an end. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Elsewhere in Europe, particularly in the Netherlands, medals were produced that mocked and satirized the official French medals.

Medal with the Duke of Savoy as Jupiter in the form of an eagle, striking down Phaethon with a thunderbolt. Made by Jan Smeltzing, Netherlands, 1706. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

These rival medals showed the French sun eclipsed by the zodiacal signs of his enemies, the ‘Sun King’ as Phaeton, falling through the sky after being ejected by Jupiter from Apollo’s chariot, and Louis as an old man being roundly beaten by Queen Anne.

The great 1702 publication of the Medallic History, intended to carry its message throughout Europe was an immensely ambitious and luxurious publication: it even had one of the most famous of all typefaces, Roman du Roi invented for it.

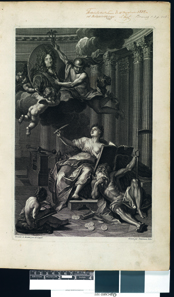

Frontspiece, Medallic History of Louis the Great, 1723. Father Time lies defeated by the medallic history of Louis XIV which will last forever. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The volume opens with a frontispiece depicting Father Time, lying defeated by the medallic history which was intended to last forever.

Siamese Ambassadors, 1686. The ambassadors of King Phra Narai of Siam [Thailand] were received by Louis in the Galérie des Glaces at Versailles on 1 September, 1686. After the visit, one of the ambassadors said that after the three grandeurs of the world, he now knew a fourth – Versailles. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

What survives today is a fascinating and unique self-portrait of a regime which dominated Europe for nearly sixty years, and which established the primacy of French taste and French culture for over a century.

For more information on the British Museum go to the museum’s website.