translated by Annika Backe

Legend has it that on January 24, 1848, the carpenter James W. Marshall discovered gold on the land owned by Johann August Sutter, thus triggering the California Gold Rush. At that time, hundreds of thousands flocked into the country and made the recently annexed territory a booming economic sector which was incorporated as the thirty-first state into the United States of America on September 9, 1850. Less than two years later, on July 3, 1852, the Federal Government decided to set up a mint in San Francisco, which, after New Orleans, Dahlonega, Georgia and Charlotte, North Carolina, would be the fourth branch of the Philadelphia Mint that had opened in 1792.

50 dollars octogonal 1852. Issued by the United States Assay Office of Gold, San Francisco. From Künker Auction 271 (2016), 667.

However, it took two years before the first mint actually began to serve. In the meantime, the former watchmaker Augustus Humbert worked as an official gold assayer in San Francisco and had, from the gold he had checked, semi-official gold coins minted which were well received by officials as payment for taxes and tariffs.

1 dollar 1856, San Francisco. From Künker Auction 271 (2016), 652.

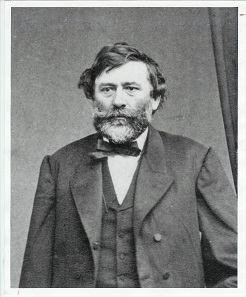

On April 3, 1854, the first national mint opened its doors in San Francisco, of which we have no photo whatsoever – even though, generally speaking, we have many illustrations that date to that era. Back then, the Mint was located on the outskirts of the financial district, at the Commercial Street, exactly where Augustus Humbert had manufactured his coin bars before. However, he was replaced by another assayer, the Hungarian August Haraszthy. Although he did not know very much about gold smelting – he used to work as sheriff, contractor and winegrower – he at least had some Hungarian partners who had learned the craft.

Agoston Haraszthy (1812-1869), first assayer of the Californian Mint and, because of a scandal, father of Californian viticulture.

In 1857, there was a scandal: Haraszthy was accused of having embezzled gold. But even though he was absolved of any guilt after a four-year trial, Haraszthy was fed up with the work in the Mint and returned to winegrowing in which he was more successful. As a result, he is still being praised as “Father of Californian Viticulture”.

The impressive front of The Granite Lady. Photograph: UK.

On April 1, 1873, Congress enacted a law that re-regulated the organization of the mints. While, until then, all mints, except for the headquarters in Philadelphia, had been treated as a branch, they were now classified as independent mints, to operate under the control of the Mint Headquarters Office in Washington.

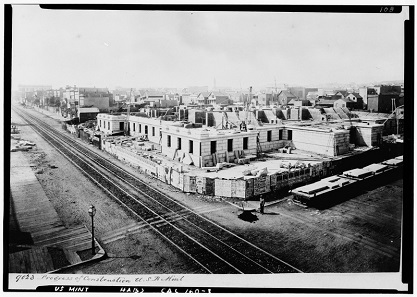

The building of the Old Mint. Photograph: Library of Congress HABS CAL,38-SANFRA,5-1.

At this time, the new, the second State Mint of San Francisco was almost finished. Construction works had begun in 1869, with a great emphasis placed on making the building earthquake-proof. The building sat on a sand foundation, as state-of-the-art technology of the time. No expenses were spared for the building. The sandstone was brought from Canadian Newcastle Island whereas the granite that was to lend its name to the Mint as “The Granite Lady” came from Northern California.

20 dollars 1874, San Francisco. From Künker Auction 117 (2006), 5743.

In addition to gold and silver coins, San Francisco was the first mint, besides Philadelphia, to produce small change made of base metal, such as the bronze cent pieces starting in 1908. The mintmark S for San Francisco, in use since 1854, remained unchanged.

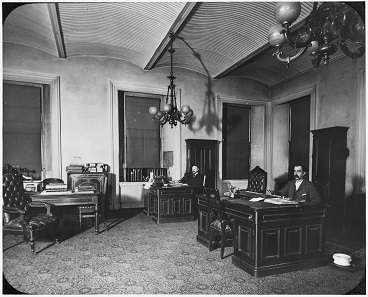

The reception office for the general public. Photograph: Library of Congress HABS CAL,38-SANFRA,5-32.

Numerous extant photographs illustrate the Old Mint’s daily business. In this example we see the reception office for the general public where raw precious metal could be handed in for coinage into dollars.

The former reception office, freshly restored. Photograph: UK.

Today, the rooms are newly renovated and you really have to have a good deal of detective instinct to imagine their former function.

Perhaps this served as the assayer’s office once. Photograph: UK.

Here we see two assayers at work. Please note the closed window. The heavy padding was intended as a safety measure, to prevent a bullet from penetrating the windows.

Assayers at work. National Archives and Records Administration 296547.

From the floor plan, the picture could have been taken in this renovated room.

A clear indication that a heavy weight stood here once. Photograph: UK.

However, heavy reinforcements on the ground indicate that weighty objects stood in these rooms once.

A view of the minting room. Photograph: Library of Congress. HABS CAL,38-SANFRA,5-31.

Perhaps coins were being minted here.

A Morgan & Orr coining press. Photograph: Wikipedia / David Shankbone.

The minting was probably done with coining presses of Morgan & Orr, such as this one, which were constructed for the then brand new Mint in 1873.

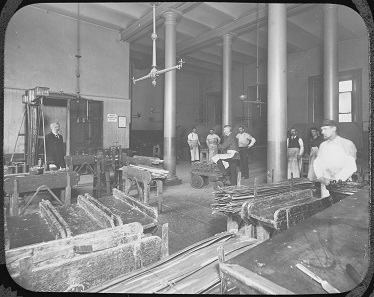

A look at the processing of precious metal. Photograph: National Archives and Records Administration 296555.

On the same floor, the smelting plant and the blank production were located.

The renovated room. Photograph: UK.

Perhaps the picture was taken in this room. The floor would fit.

Another one of the renovated rooms. Photograph: UK.

Here, the former floor was replaced with bright parquet. However, the simpler chandeliers – at least when compared against the rooms where the workers wore a white shirt – are also clearly recognizable on the old pictures.

The chimneys of the smelting plant. Photograph: UK.

The former chimneys of the smelting plants are still clearly visible today.

A view into the basement where coins and bars were stored. Photograph: UK.

When you visit The Granite Lady today, it is the basement where you believe you could feel the atmosphere of the past most of all. Here, the safes were standing where, behind thick iron doors, the gold and silver bars as well as the coined money were stored.

The walls are more than stable. Photograph: UK.

How thick the walls really are was shown to us by Devyn McNichol who gave us a tour of the rooms.

The closed safe. Photograph: UK.

A safe cannot be opened. Of course, everyone joked that this is where all the gold is hidden.

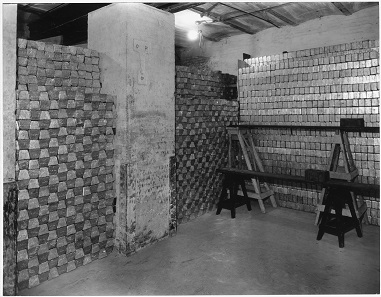

A view, as it might have looked like in such a room in 1935 or so: the variant with bars. Photograph: National Archives and Records Administration 296609.

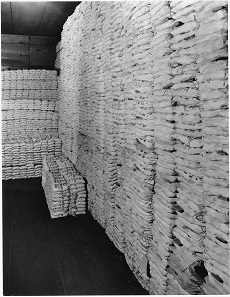

And these bags contain coined gold. Photograph: National Archives and Records Administration 296610.

What it might look like behind the closed door becomes apparent by two images dating from 1935 when the rooms were jam-packed with gold and silver.

San Francisco after the earthquake, a view from the Mint’s roof. National Archives and Records Administration 296588.

On April 18, 1906, the earth shook in San Francisco. With a strength of 8.4 on the Richter Scale the stable houses crashed down like houses of cards. A fierce fire followed next. Around 3,000 people are said to have been killed in this earthquake.

The Mint after the quake. National Archives and Records Administration 296587.

But the Mint survived. Its rugged construction, combined with the foundation designed for earthquakes, had prevented the collapse. The fire was fought by the Mint’s staff with a water hose and water coming from a source located on the premises.

50 dollar 1915, San Francisco. Commemorative coin for the Panama Pacific International Exposition. From Sincona Auction 5 (2012), 91.

They saved the Mint. And the minting could be resumed. This made The Granite Lady become responsible for the economy in San Francisco not coming to a halt, despite the severe damages.

A sign that San Francisco, only a few years after the disaster, had returned to its former importance is the great Panama Pacific International Exposition, for which the San Francisco Mint manufactured commemorative coins in the value of 50 dollars, which, until 2010, were the largest and heaviest gold coins ever made by a US Mint.

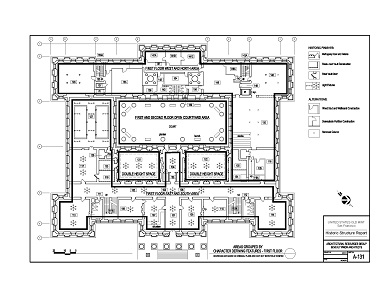

Map of the Mint. Source: NonPlusUltra.

In 1937, after 63 years, the Mint abolished its Granite Lady, and moved into the new building where the American coins are still being minted. Afterwards, offices were located in the Old Mint, until, in 1972, the Mint repurchased its building to set up a museum, which was in operation until 1994. In 1997, the Mint sold the building a second time.

What will happen next with The Granite Lady is written in the stars. Currently, it is rented for events, and whoever wants to marry in the premises of the Mint, for example, can turn to the NonPlusUltra agency. On the website you can see both the floorplan of the building as well as numerous atmospheric images of the premises.

Next week, we will report on the new Mint of San Francisco, to which we have also been granted access.

We would like to thank Mary Lannin, who organized this visit and made it possible in the first place. We are also indebted to Devyn McNichol of NonPlusUltra who gave us a tour of the Old Mint’s premises.

An incredibly rich selection of pictures from the Old Mint offers inexhaustible Wikipedia, without which our contribution would have been much more boring.