with the kind permission of the MoneyMuseum

Our series ‘The People of Zurich and their Money’ takes you along for the ride as we explore the Zurich of times past. In this instalment, you’ll get to read a dialogue between a buyer from out of town who’s trying to pay for his purchases in the year 1335. Much like a good DVD, this conversation comes with a sort of ‘making of’ – a little numismatic-historical backdrop to help underscore and illustrate this conversation.

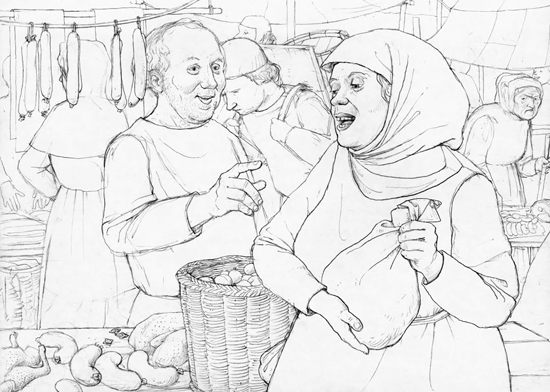

1335. An out of town buyer tries to pay for his purchases at the market in Zurich. Drawn by Dani Pelagatti / Atelier bunterhund. Copyright MoneyMuseum Zurich.

Market woman: That’s it. Or do you need anything else?

Client: No, I think that’s it.

That’s 4 shillings and 8 pennies.

I didn’t have time to change my money, but I still have some Zurich pennies from my last visit.

Show them to me. (Break) Sorry, I can’t accept them.

Why not? These aren’t pennies from Bern or Solothurn. I know that those pennies are forbidden. This is Zurich money. It was you that gave me pennies as small change.

Yes, that’s true. But in the meantime the council has decided to bring out new pennies. They’ve forbidden us to accept the old ones. Listen, if they caught me with your pennies, I’d have to pay a heavy fine, just like you would.

You’re kidding! You mean I’d have to pay a fine for paying with your own coins?!

Oh yes. Recently there was a decree of our council. We’re now obliged to accept only new pennies. We can change the old pennies for 3 1/2 shillings per each lot. This means two old pennies for a new one. If you want to change more than 120 pennies, you’ll have to go to the mint.

Come on, you can change the coins later. I’m in a hurry today. I’ll give you two pennies more to make it worth your while. That’s a good offer, isn’t it?

(resolute) Don’t you get it? I said no. Nobody’s allowed to accept these coins on the market. I can’t take the risk. Do you know, how much I would have to pay, if they saw me taking your coins? Five shillings!

Nobody will see it.

You’ve no idea. The crooked Gret has always been jealous, because my business prospers. She’d love to squeal on me! You’ve got to understand me!

Then I can’t buy your merchandize. I really don’t have the time today to go and change my money.

Shit! You haven’t any money with you apart from old Zurich pennies, have you?

I’ve got a bit of this and that.

So, I’m allowed to accept pennies from Constance and Strasbourg. I also can take kreutzer, turnoses and of course soldini from Venice. But I’ve no idea what they’re worth today. I’ll have to ask.

Please ask, I’ve got some pennies of Constance and some turnoses. Maybe we can still do business together.

Let’s hope so! Hang about, I’ll be with you in a minute.

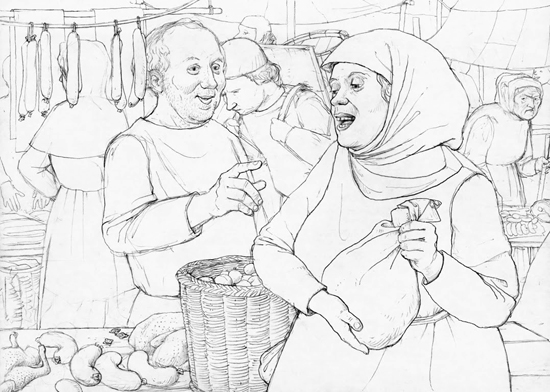

Zurich. Bracteate, around 1320. Bust of the abbess of the Fraumünster Abbey from the front. From coins and medals auction 35 (2011), 576.

Making of:

In 1336, craftspeople stormed the town hall of Zurich. The reasons for their uprising were outlined in the so called ‘first juror letter’ and indicated that city council, through its unequal jurisdiction, arrogance and misappropriation of public funds, had incited great anger in the townspeople. A great deal of this anger was likely due to a special decree that Zurich council had enacted in 1335. This decree had banned the use of old Zurich pfennigs.

In nine paragraphs, council stipulated precisely how all payment transactions in Zurich should function. Paragraph 1 forbade payment using old Zurich currency, with the threat of severe penalties. The fines were carefully regulated in a subsequent insertion, such that we can state in our dialogue exactly how much the market woman would have had to pay had she been caught during the transaction.

The second section addressed the matter of foreign visitors to the market. In order to safeguard them from being taken advantage of due to ignorance and inexperience, the act explicitly forbade the people of Zurich from ‘palming off’ their old pennies to foreign vendors. Whoever still had old pfennigs on hand – like our patron in the audio drama – could exchange them at designated change bureaus overseen by the city. The Zurich council set up three changeover sites, with two smaller branches, one on each side of the Limmat. There, smaller amounts under 120 pfennigs (= 10 shillings) could be exchanged. Anyone who had more old pennies than that had to look to the mint for assistance. Of course, the mint didn’t just have the monopoly on exchange transactions, but also held sole trading rights for crude silver.

Cologne. Tournois of Walram, Count of Jülich, undated (1343), Deutz. From Künker auction 44 (2005), 594.

Three paragraphs were devoted to foreign currencies. Prior to the middle of the 19th century, there was scarcely a single city or country capable of minting enough coins to supply their own currency zones exclusively with their own stampings. Nevertheless, it was still in the interest of the authorities to monitor which coins were circulating on their market, and Zurich city council stipulated in the edict which currencies could and could not be accepted.

Since Zurich itself was not permitted to mint gold coins at the time and was entirely reliant on foreign imports, all gold coins were accepted as valid currency. Silver coins were also accepted, provided they were well known for the stability of their weight and silver content. These silver coins included French tournois, soldini from Venice, Tyrol kreutzers, hallers from Schwäbisch Hall, as well as Strasbourg and Constance pennies. The use of Bern, Burgdorf and Solothurn currencies was strictly forbidden. Pfennigs from these cities didn’t even change hands in the mint. Freiburg, old Basel and Zofinger pennies could be accepted and were paid by lot, so 14.82 g. got you 48 new Zurich pfennigs. All other pfennigs were exchanged for 39 new Zurich pfennigs per lot.

The edict offers us valuable insight into how difficult it must have been for merchants just to familiarize themselves with all the foreign currencies and exchange rates. It’s hardly any wonder that our market woman has to check first before she accepts her customer’s tournois and soldini. Mind you, this was also a device to aid in our lack of knowledge – very rarely are we familiar with the exchange rates of these coins.

It goes without saying that the alteration / falsification and smelting of Zurich coins were also strictly forbidden. This is explicitly laid out in the last section of the edict.

While we’re at it, let’s just briefly talk about the historical context of this document. In 1330, the free imperial city of Zurich, along with St. Gallen, Schaffhausen and Rheinfelden, pledged itself to the Habsburgs. Emperor Louis the Bavarian was, in effect, planning to sell the four cities for a total of 20,000 marks silver. City council was obviously intent on preventing this move, as it would have meant significant limitations on Zurich’s freedom. And so, with the help of bonds from rich citizens and loans from the Jews and the Cawerschen, council succeeded in raising enough money to meet the emperor’s needs.

This money obviously had to be recouped through direct or indirect taxes with interest and compound interest. To this end, they also made use of the means of money deterioration. By this time, it had become common practice for the abbess of the Fraumünster to lease out coinage routinely to Zurich council members so that the city could have a significant say in it.

It’s likely that city council had decided prior to 1335 to repeal the deterioration of the coinage and to create currency devaluation. The inferior coins yielded a great seigniorage for the city, buy were not accepted with good grace in other cities. Council then reverted to the coins’ original weight and silver content. Anyone who exchanged old Zurich pfennigs for new ones would now only get one new pfennig for two old ones. As such, those who had their cash at home in Zurich pfennigs lost half their holdings, while merchants, who tended to save their money in gold and large silver coins, emerged relatively unscathed. The currency reform hit the small craftspeople particularly hard. It’s hardly surprising that there was so much anger over the governing of the city; so much so, that a mere one year later, Rudolf Brun succeeded in pushing through his new Guild Constitution with the aid of those societal classes who were particularly aggrieved and hard hit by this coin edict. Of course, the new city regiment immediately assumed minting rights under his supervision.

In the next instalment, we’ll hear what Rudolf Brun was all about and why aristocrats had to earn money.

You can find all other parts of the series here.

The texts and graphics come from the brochure of the exhibition of the same name in the MoneyMuseum, Zurich. Excerpts with sound are available as video here.