by Ursula Kampmann

August 18, 2011 – Stageira, Neapolis, Mesembria, Maroneia and Abdera – these are today’s destinations. We see magnificent archaeological excavations that are particularly well-kept. On the other hand, we experience some a disappointment. As always, it is going to be a colorful kaleidoscope with impressions from Northern Greece…

Day 24, July 4, 2011, Native town of Aristotle

One is inclined to think that four and half weeks are endless. But there come a time when one realizes than time is getting short with all the things left to see. One sits down and discusses which excavations are at the top of one’s list and realizes that one urgently needs to change quarters again. And that is a pity for there is no place in Greece more beautiful than Sithonia.

View at the town wall of Stageira. Photograph: KW.

We drove along the coastline east and passed Stageira which is first and foremost known as native town of Aristotle. The larger than life monument of him isn’t situated here but in modern Stageira, roughly 30 kilometers away. Why it was erected at such great a distance? Well, most of the seemingly Old Greek names were given to the modern communities as late as the 19th century, sometimes even in the 20th century. Back then, the communities were deliberately renamed in order to Grecize all the names from different languages. The idea was to turn the ethnically heterogenous population into Greeks who consider themselves heirs to ancient Greece – and that mission was accomplished.

Admittedly, sometimes something went wrong when renaming. Ancient Stageira simply wasn’t discovered yet, when around 1920 Dogatzi was named after the ancient city thought to be located nearby. That makes modern Stageira with its huge memorial for Aristotle being a half an hour drive remote from the ancient settlement.

Stageira. Tetradrachm, c. 520-500. Lion slaying a boar. Rev. Quadratum Incusum. From auction NAC 52 (2009), 96.

Stageira was founded in the middle of the 7th century. It is said that Ionians from the Greek island of Andros looked for a new home there. They made a good choice. The magnificent port, the proximity to the resources of the North – gold, silver and wood – made the city rich. We know only of Archaic coins associated with Stageira. The most famous ones are the tetradrachms which bear so much resemblance to the pieces from Akanthos. There are others, however, which show a standing wild boar. Anyone visiting the excavation site of Stageira understands the connection with the arboreous surroundings of the city.

Stageira(?). Trihemiobol, 520-480. Protome of a horse with three blossoms. Rev. Floral ornament. From auction Tkalec AG Mai 2011, 15.

Another type of coin associated with Stageira shows a charming flower motif on the obverse. We don’t know if Stageira was forced to surrender to Xerxes. According to Herodotus, he simply marched pass Stageira. At any rate, Stageira was a member of the Delian League with a tribute of one talent per year.

During the Peloponnesian War it supported Sparta and hence became a free city after the war was over before it joined the Chalkidian League. In 349, Philipp conquered and destroyed Stageira as well. At that time a son of the city already lived at the royal court: Aristotle, teacher of Alexander. The latter allegedly asked his father to re-found Stageira, which he did. The city, however, never rose again to its former bloom – Strabon even wrote around the turn of the centuries that the area was deserted. Only 1000 years later, another settlement came into being at the very site to which the marvelous medieval wall belongs, visible from afar.

Early Classcial fortifications of Stageira. Photograph: KW.

There are few archaeological excavations so nicely located as Stageira. There are fine paths, overgrown with lush green vegetation, for tourists to visit the ruins.

Detail of the so-called “Egyptian masonry”. Photograph: KW.

The wall, with a modern path alongside it, is particularly impressive.

Excavation map. Photograph: KW.

We would have liked to see the entire archaeological site but people are the sum of their experiences. Stageira is remote. Our car, packed with things we needed for our trip East, was well visible from the street but completely unguarded. In a similar situation, when we visited Southern France the previous year, the windows had been smashed by someone who wanted to get his hands on our “treasures”. We simply had no peace even though we assured ourselves the entire half an hour we spent on the site that nothing similar was going to happen here in Greece. At some point we realized that we didn’t enjoy the tour due to our worries about a break-in.

View at the city hill with the ruins of Stageira. Photograph: KW.

We had one last look at the excavation site, accursed the South-French burglar for dashing our faith in man and left.

Acropolis of ancient Neapolis. Photograph: KW.

We took quarters near Kavala. As we know from inscription finds, ancient Neapolis was situated there once, most probably built by Thasos.

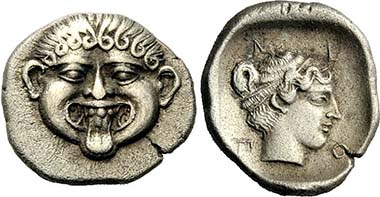

Neapolis. Obol, c. 525-490. Gorgoneion. Rev. Foud-field Quadratum Incusum. From auction Lanz 149 (2010), 101.

We know of many coinages of Macedonian Neapolis so that the idea of a city, being member of the Athenian Alliance with a tribute of only 1,000 drachmai – only a fraction of what Akanthos (18,000 drachmai) or even Terone (36,000 drachmai) were obliged to pay – seems astonishing. Perhaps this modest tribute was the reason why Neapolis was on Athens’ side during the Peloponnesian War and was still loyal to Athens in the conflicts with Philipp II. The Macedonian king conquered the city in 355.

Neapolis. Triobol, late 5th-4th cent. Gorgoneion. Rev. City nymph. From auction Lanz 151 (2011), 346.

The later history of Neapolis was shaped by the Via Egnatia of which the city was an important station. It was here where Brutus and Cassius dropped anchor before they were defeated in the battle at nearby Philippi. During Roman imperial times, Neapolis was not a free city but administrated as port of Philippi.

Mosaic showing Paulus asked by Jesus Christ – which bears resemblance to Aleaxander -, to missionize the Macedonians. The city of “Troas” in the background is especially nice. Photograph: KW.

Apostle Paul arrived here before he traveled to Philippi. Today, Kavala is proud of being the first city in Europe Paulus has set foot in. From the 9th century onwards, the city was called Christupolis and was a bishop’s see. In contrast to Philippi, which was long gone, the port flourished. That, however, made it a frequent victim during the Crusades. The name of Kavala dates back to the era of the Franks who had established a horse changing station here. In 1387, the city was conquered by the Ottomans of whose reign many buildings still bear traces.

Signpost indicating the way to Istanbul. Photograph: KW.

It is perhaps due to the very Ottoman past, which by the way is quite present in Kavala with its extensive redecorations, that Greek nationalism is paid homage. At any rate, right beneath the big aqueaduct there is huge signpost stating the distance to Imperial city of Constantinople which doesn’t look like any of the usual road signs in Greece.

Aquaeduct of Suleyman. Photograph: KW.

This big aqueaduct isn’t as Roman as it seems. Following Roman models, it was erected under Suleyman the Magnificent (1520-1566) to ensure the water supply of Kavala. That was part of the building operations Suleyman organized to restore the fortification and the port.

Parking Greek style. Photograph: KW.

Wandering the narrow pathways uphill one is surprised that here, where every German would expect a pedestrian zone, loads of cars are parked.

Castle of Kavala. Photograph: KW.)

We had come across quite an extent of kindness so far, but we found it particularly nice when a totally unknown woman, who sat on a balcony and had noticed our searching looks, addressed us and led us the way to the castle. And that was topped. I had put my camera bag in my pocket and somehow it had fallen out. Since we didn’t notice we walked on when, perhaps five minutes later, a motorcyclist sounded the horn. He had found the bag, associated it with the two tourists, tracked them and finally handed it over, beaming. I went on being happy about this kindness for the entire day.

Court of the castle. Photograph: KW.

Kavala’s main attraction is the castle which dates back to the Franks. They allegedly have used ancient spolia for the building. It is possible to visit the site, which provides a marvelous view at the port, for a small fee.

Recently redecorated mosque on the city hill. Photograph: KW.

Kavala is the birth place of Muhammad Ali who ruled from 1805 to 1848 as vice king of Egypt. His father had been a wealthy merchant in Kavala who exported tobacco that is cultivated in the area until the present day. Muhammad Ali made a career in the administration and the military and made use of the vacuum in Egypt, when the Napoleonic troops had been withdrawn, to establish a virtually independent empire here. Blessed with the riches of Egypt, Muhammad Ali supported its birth place Kavala and had some lavish building complexes erected which can still be visited.

Yet another long and eventful day has gone by. For the following day we had planned a trip to Thrace. From Kavala as base camp we would head for Mesembria, Maroneia and Abdera to see with our own eyes the places such beautiful coins came from.

Day 25, July 5, 2011, Thrace

We had a 417 km drive ahead with our excursion to Thrace. It was only possible to master this long a distance because of the new railway destination East. It is toll although nothing is charged yet. The development of the road in regard to infrastructure becomes clear when looking at a map, where the white roads – as stated in the map legend – are marked as ‘barely passable’, which have nothing in common with our well-maintained bike ways.

Archaeological excavation of Mesembria-Zone. Photograph: KW.

Our first station was Mesembria, situated most remote from Kavala. We had gone up early this day, as early as possible in a Greek hotel when one wants to have breakfast there. By now, we had acknowledged that almost all Greek archaeological excavations stick to the usual opening hours from 8 a. m. to 3 p. m. That, however, makes it tricky to have breakfast since no hotel starts serving before 8 a. m. But still, shortly after 10 a. m. we arrived at Mesembria.

Archaeological excavation of Mesembria-Zone – kept in an exemplary manner. Photograph: KW.

The buzzing sound of our car startled up a few people at the excavation site. The guard came instantly running to see if there were really some tourists arriving. He rushed to unlock the restrooms (very sensible!) and hurried to his box office to sell us tickets for 2 Euros. He didn’t seem to do that very often. And indeed, the roughly 2 hours we spent in Mesembria we were the only tourists.

Mesembria. AE, c. 450-350. Corinthian helmet. Rev. Wheel with four spokes. From auction Gorny & Mosch 191 (2010), 1175.

It is likely that there was an early settlement on the island of Samothrace, situated opposite, already around 700 B. C., to control the trade with the rich grain-growing regions of the Black Sea. The settlers of Samothrace founded colonies on the fructiferous mainland on their part. Amongst them were Mesembria, Drys, Zone, Sale, Tempyra and Charakoma. The ancient historians reveal nothing at all about these settlements. There is only one exception: Herodotus tells of the Persians passing Mesembria as the first station on their march from the Hellespont to Greece.

Mesembria. Tetradrachm following the Alexandrian type, 250-175. Mint mark: Corinthian helmet and DI. From auction Gorny & Mosch 186 (2010), 1279.

By that, the Archaeologists were made to believe that the ruins located at the far east of Thrace had to be the city of Mesembria. Unfortunately, the results of the archaeological excavation pointed in another direction.

Zone. Bronze, around 350. Head of Apollon. Rev. Lyra. From acution CNG 145 (2006), 49.

More than 2,000 coins from the city of Zone were unearthed. This comes as a surprise for there are hardly any of these coins present on the market. It seems likely to assume, therefore, that the excavated place is not Mesembria but Zone. And that would mean that the entire traditional arrangement of the colonies would be null and void. There is, however, another possibility: perhaps Mesembria was the old and Zone the new name of the city, even though that would contradict Herodotus who mentions both cities in the same breath.

View at the archaeological excavation. Photograph: KW.

Anyway, Mesembria-Zone is an archaeological excavation very suitable for tourists that doesn’t deserve being poorly visited. Expensive wooden paths had been built to lead the tourists to the site’s different attractions, of which there are plenty. They all are splendidly commented on by Greek-English explanation panels.

129 amphorai upside-down. Photograph: KW.

The main attraction are two rooms with any number of amphorai standing on their head. They were produced in the late 6th and 5th centuries, and some had been attributed to a workshop on the island of Chios. Archaeologists assume today that these tubular parts were placed underneath the floor to protect the room from becoming moist.

An ancient amphora re-used as modern beehive. Photograph: KW.

The bees don’t care. They have made the amphora their new home.

Sieve for wine exctraction. Photograph: KW.

A flat clay object with holes, on display adjacent to the amphorai, allegedly was used to extract must from the grapes.

Ancient grape press. Photograph: KW.

This tub, too, once served the wine extraction. The grapes were pressed here.

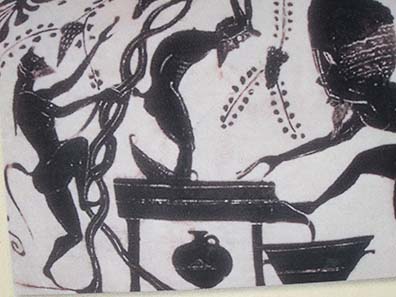

Satyrs treading. Photograph: KW.

This picture from an explanation panel gives a pretty good impression of what treading with such a plane tub once looked like.

View at the archaeological excavation, in the background Samothrace. Photograph: KW

I am a master in map reading. Hence I dared to head for Maroneia not via the railway, with a 40 km detour, but via a small, white path which connects Mesembria with Maroneia, which is roughly 14 km away. That, however, was a mistake as we soon realized, when being stuck on an abominable earth road not even a mountain biker would use. We had some trouble in finding a place for turning around, and then drove the detour all the same which surely took us quicker to Maroneia than the shorter earth road would have done.

In Thrace, the ancient Via Egnatia ran parallel to the railway. Photograph: KW.

We were rewarded with a view at the ancient Via Egnatia which is partly signposted and walkable.

Maroneia. Stater, 386-347. Horse jumping up. Vine stock, surrounded by an official’s name and a cicada. From auction Gorny & Mosch 195 (2011), 107.

Who doesn’t enthuse about the beauty of the marvelous coins of Maroneia. The horse on the obverse, the lush vine branch on the reverse plus a cicada in addition: of course we were anxious to see what is still left to see of Maroneia, especially because our guidebook wrote promisingly:

Cicada, not on a coin this time but in the flesh. Photograph: KW.

“Some an archaeological site in Greece is situated in scenically magnificent places. Maroneia, however, casts a real spell on virtually every visitor.”

Locked theater of Maroneia, accessible only via a dirt road. Photograph: KW.

To cut a long story short: we weren’t spellbound. We noticed no spell whatsoever. The individual archaeological remains of Maroneia are situated apart so that the car is required to visit them. Poor paths – no streets, rather a piste following the principle of road hole after road hole to boost the local car repair industry – turned the drive into an agony one doesn’t want to recall.

Pictures don’t give an adequate impression of the actual situation. Photograph: KW

Uphill, downhill, living in constant fear that a vehicle might come our way for there are trappy trenches by the roadside only waiting to demolish our oil trough.

Somewhere behind the fence is a part of the 10 km long town wall. Photograph: KW.

The ruins weren’t worth the strains. We didn’t see anything of the famous, 10 km long town wall. Yet, the size of the city area of Maroneia is truly impressive. The height difference alone was 700 m!

The residential house of a wealthy family with mosaic decoration. Photograph: KW.

Easily accessible, by contrast, is a mosaic that had been discovered in a residential house.

Roman gate in honor of Emperor Hadrian. Photograph: KW.

And, of course, the Roman gate in honor of Hadrian who had visited Maroneia in 124/5. Down at the port there were finally some more remains to see than uptown. Our interest, however, had already waned on the bumpy streets. In addition, we wanted to go to Abdera even though we were approaching the magical 3 p. m. threshold. Put perhaps the Abdera ruins would be out-of-town.

View from outside at the museum and the excavation site of Abdera. Photograph: KW.

Naturally, they weren’t. The museum in the city was already closed (admittedly, we arrived after 3 a. m.). So was the archaeological excavation we could only glimpsed at through a lattice fence.

Port of Abdera. Photograph: KW.

Being disappointed we drove to the port. We would have been only too pleased to see the remains of the city.

Abdera. Stater, c. 411/410-386/5. Griffin. Rev. Herakles. From auction LHS Numismatik AG 102 (2008), 104.

I am willing to own that to me the coins from Abdera range amongst the most beautiful minted ever. I love the varied depictions on the reverses. Here exhausted Herakles is shown who, according to local tradition, had founded the city of Abdera at the spot where his companion Abderos had been torn apart by the mares of Diomedes. It is said that settlers had come to Abdera in the middle of the 7th century, but they were expelled. Only the colony of the city of Teos, founded around 543, managed to survive. The standing of Abdera as intellectual center becomes evident by the list of philosophers coming from Abdera or teaching here: Anaxarchos, Demokrit and his teacher Leukippos, Hekataios, Protagoras and Leukippos of Miletus. Despite this, the people of Abdera were regarded as the fools of ancient times.

Abdera. Stater, c. 390. Griffin. Rev. female dancer. From auction Leu Numismatik AG 81 (2001), 127.

Abdera was the wealthiest and most important Greek city at the Northern coast of the Aegean Sea. It constantly flourished, even under Persian rule. The tribute it was obliged to pay to the Delian League later says it all: 90,000 drachmai (= 15 talents). Later it was reduced to 10 talents. Abdera suffered the same fate as many Thracian cities: it tried to dissociate itself from Athens, was conquered, beset by Thracian neighbors, and conquered by Philipp II. Under the Diadochs the real turmoil began. Shortly after Hadrian ist coinage came to an end and the city disappeared from the written sources.

Young storks in the nest. Photograph: KW.

Although we didn’t see much of Abdera’s archaeology, nature was overwhelming again. Every village had its avenue of power holes, with a nest on each of them where storks raised their young. Back home in Germany, the stork is not as rare as it was 20 years ago, but I have never seen so many of them in one place before.

All in all, it had been a wonderful day that we rounded off in a tavern at a public beach of Abdera. Well, we had no opulent meal, no meat, no wine, but the right serving for two hungry people to have their fill. And then came the bill, together with a huge plate of fruits for free. 6.80 Euros for the entire meal. We were almost embarassed to see how little money a cook and a waiter earned around here.

The next issue of our little numismatic diary is devoted to the cities of Amphipolis, Philippi and Pella. Bit by bit we draw to a close since these three excavations were the last stations of Northern Greek terrain.

You can read all other parts of this diary here.