by Ursula Kampmann

August 11, 2011 – Illustrious names spring to mind when thinking of Chalkidiki. Akanthos and Terone, Uranopolis and Olynthos. But not everywhere reality answers expectations…

Day 20, June 30, 2011, Chalkidiki

Chalkidiki is a tourist paradise that covers an area of 2,918 km2 with 522 km coast. Whereas the Greeks dream of a complete development for tourism with huge hotels, the tourists who visit the middle of the three peninsulas, Sithonia, year after year hope for these aspirations to be dashed.

View at the sea from our veranda. Photograph: KW.

In contrast to Kassandra, which is completely in the hands of package tourists, on Sithonia there are still some paradises to discover left: small, unpretentious, well-kept hotels where the dishes, not spoiled by the tourist food of the South so far, are prepared by the owner himself and served by his daughter. In addition, the visitor experiences wonderful landscapes with rocky bays, a clear sear and a vegetation that is barren at the coastline and lush in the hinterland.

Drive alongside the rocky coastline of Sithonia with a view at Athos. Photograph: KW.

“Compared to their natural beauties, the region has few things to offer to the one interested in art, despite its rich history.“, say L. Schneider and C. Höcker in their guidebook to art. The numismatist, however, associates some of the most impressive names of the history of money with Chalkidiki: Potidaia, Mende and Skione for Kassandra, Terone for Sithonia as well Akanthos and Uranopolis for Athos. Additionally, Olynthos is near-by where the Chalkidian League minted their gorgeous tetradrachms, and not to forget Stagira, famous not so much for its coins as for being the place where Aristotle was born.

Day 21, July 1, 2011, Round-island trip on Sithonia

The round-island trip we made on the first day took us to ancient Terone.

The seafront of Toroni, all dressed up. Photograph: KW.

Terone, called Torone by everyone except numismatists, is situated near present-day Toroni that likes to become established as a center of tourism thanks to its tremendous sandy beach.

To achieve that, the sea front gets dressed up with pavement, lamps, benches and transportable toilets. The hotel owners don’t care about the few archaeological remains, probably because barely any of the sun-seeking tourists shows any interest in them. Terone is one of the historically important cities of Northern Greece, at that.

Terone. Tetradrachm, around 480. Oinochoe with vines. From auction Künker 94 (2004), 633.

Terone appearing in mythology testifies to its great age. Toroni – that was how the wife of Proteus was called, god of the sea. She gave birth to two sons that were to be defeated by Herakles later. The earliest testimony of the historical significance of the city is its coins from the 6th cent. Due to its magnificent port, the city ranged amongst the most important trade centers of Chalkidiki, which is supported by the fact that its annual toll as member of the Delian League was 36,000 drachmai (= 6 talents).

Terone, AR (0.33 g), late 5th cent. B. C. Av. Crane with its head in an oinochoe. From auction Gorny & Mosch 186 (2010), 1230.

This is not the place to portray the checkered history of the city between Athenians, Spartans, Persians and Macedonians. Terone had become the victim of war too many times. Suffice it to say that historians refer to the city as an important port still in reports about the conflicts between Rome and Perseus in the 2nd cent. B. C. Terone most probably continued to be important in Byzantine times, too. This is corroborated by numerous archaeological remains and the fact that today it is a titular see of the Catholic Church. The Vatican needs titular sees to appoint the personnel bishops the Vatican can’t do without. Because the general duty of a bishop is to care for the flock of his bishopric, the titular sees, where no Catholic live, provide a formal a way out of the canon law.

Ancient court walls with view at the Byzantine fortress. Photograph: KW.

A major part of ancient Terone is underwater today. What wasn’t under water, fell victim to road works. In the early 20th century the Ottomans commisioned an engineer with building a network of streets on the rutted island. He saved his bosses a lot of money when he used the scattered stones of Terone as seating for the new streets.

Works in Progress – since 2004 or again? Photograph: KW.

Of course, one can’t visit the Byzantine fortress. When we visited it the first time, in 2004, we couldn’t either. “Works in progress” gives cause for hope. I have to admit that I was tempted to call the number stated on the poster where further information was said to be provided. It would have been so fascinating to see how people react to such a call…

Further archaeological remains. Photograph: KW.

Open to the public, by contrast, was the clearly not spectacular rest of a wall belonging to an unspecified building.

Grasshopper as photo model. Photograph: KW.

Much more spectacular was this huge grasshopper which posed confidingly for our camera. Whenever archaeology didn’t offer anything the Greek fauna made it up (and sometimes the Greek amphibians and insects ran rings around the archaeological attractions).

Funerary chapel alongside the way. Photograph: KW.

Several times already we have noticed small chapels alongside the way with one or more icons and frequently the faded picture of a man or a woman (generally more men than women) and a light. We were told in our hotel that this is the Greek way to commemorate those who had died in a car crash. Bearing this information in mind, we were horrified of the number of chapels on our way. On the other hand, this comes as no surprise for Greece, together with Bulgaria and Lithuania, tops the list of deaths on the road in Europe. According to an EU statistics from 2009, roughly 150 people per million inhabitants died there. (For comparison: in Germany, where there is a higher degree of motorization, the ratio is 79.) By the way, the areas we traveled were relatively safe: on the Peloponnese, 251 deaths on the road per million inhabitants are registered.

Several times already we have noticed small chapels alongside the way with one or more icons and frequently the faded picture of a man or a woman (generally more men than women) and a light. We were told in our hotel that this is the Greek way to commemorate those who had died in a car crash. Bearing this information in mind, we were horrified of the number of chapels on our way. On the other hand, this comes as no surprise for Greece, together with Bulgaria and Lithuania, tops the list of deaths on the road in Europe. According to an EU statistics from 2009, roughly 150 people per million inhabitants died there. (For comparison: in Germany, where there is a higher degree of motorization, the ratio is 79.) By the way, the areas we traveled were relatively safe: on the Peloponnese, 251 deaths on the road per million inhabitants are registered.

Day 22, July 2, 2011, Olynthos and the Chalkidian League

After a refreshing bath in the morning we broke away from our Arcadian setting to make a trip to Olynthos and Polygyros.

Map of Olynthos, a city designed on the drawing board. Photograph: KW.

Olynthos was mentioned for the first time in the context of the Persian Wars when the Persians conquered the city, killed the population or enslaved people and handed them over to the Chalkidians for resettlement. Only some decades later, Olynthos appears as member of the Delian League with 2 talents (= 12.000 drachmai) annual toll.

Soon, however, the challenging claims of the Athenians displeased entire Chalkidiki. The inhabitants of a number of cities decided not to agree to the demands anymore. When subsequently Athens attacked the cities in 432 B. C. with its fleet, the city councils decided to abandon the small individual settlements to unite themselves in a heavily fortified city for defense.

The remains of the excavations make this irregular way of construction visible.

Photograph: KW.

Olynthos was chosen as center. In addition to an already existing older area of the city a nearby hill was accessed and secured with a city wall that didn’t survive until the present day. The area was divided in equally big parcels and every citizen was allotted one of these. It is very likely that approximately 6,000 people moved to Olynthos back then. They came from Podidaia, Mende, Skione and Terone.

Chalkidian League. Tetradrachm, Olynth, c. 410. Apollon. Rev. Kithara. From auction Gorny & Mosch 195 (2011), 123.

Coins showing the head of Apollon on the obverse, ranging amongst the most beautiful ever produced in antiquity, bear witness of the alliance of the Chalkidian cities.

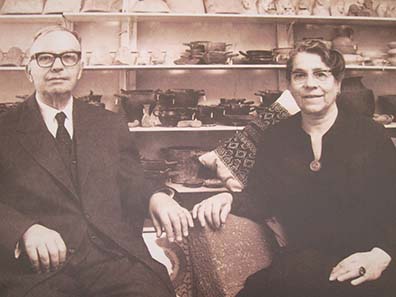

D. M. Robinson on the archaeological excavation of Olynth. Photograph: KW.

If you have ever wondered how D. M. Robinson looked, who wrote the standard and still used reference on this coinage, you get the answer by looking at him here, during the excavation of the south hill.

View from the city hill of Olynthos to the lowlands. Photograph: KW.

Olynth was well-fortified and able to withstand for almost a century. In 348, however, the troops of Philipp II conquered the city after a long-term besiege. Once again, the people were killed or enslaved. But this time, the city wasn’t rebuilt.

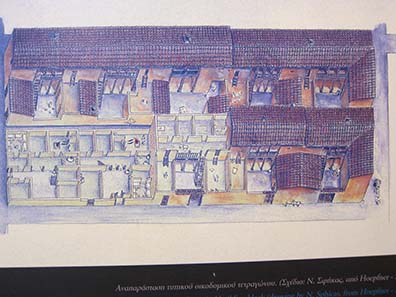

Reconstruction of a block of houses. Photograph: KW.

To us that means than Olynth, more than any other city, gives us an idea about how people lived in the middle of the 4th cent. On the basis of the ground plans the houses can be reconstructed. Even though they were all erected on an equally big parcel of land, they differ considerably in regard to room layout and decoration.

Mosaic: Bellerophon on Pegasos fighting Chimaira. Photograph: KW.

In some of the houses gorgeous pebble mosaics can be found, like the ones we rather know from Pella.

Ancient bath tub. Photograph: KW.

To me even more impressive were the bath tubs one can see in the area.

Clay model of a woman bathing. Photograph: KW.

How they were used is demonstrated by clay models of a woman bathing in a tub.

Tortoise. Photograph: KW.

The highlight of Olynth was not a ruin but a little tortoise. One can see its conspecifics relatively often in Northern Greece; during our voyage we had done very much for the preservation of the species. Every time we came across such a small animal on the street we stopped and carried it on the other side. Oh well, one experiences quit a lot. If you ever have the idea of saving a tortoise grab it at its sides and carry it at a good distance to your own body. The creatures usually secrete drops of a smelling liquid once they notice they are lifted up.

Tortoise and snake. Photograph: KW.

The Greek tortoise is “mostly herbivore” – if it takes a chance here to make its diet more diversified with this dead snake we couldn’t figure out.

Ancient door knocker from Olynthos. Photograph: KW.

Close to Olynthos the modern provincial city of Polygyros is situated with a museum on its fringe which houses the finds from some of the cities of Chalkidiki. Many exhibits testify impressively the once lavish decoration of the houses. No wonder because mainly the wood as raw material, required for building ships, made the people rich.

Gold cast of a tetradrachm from Akanthos. Photograph: KW.

In Polygyros we discovered another gold cast of a tetradrachm from Akanthos. A similar piece we saw in the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki.

Gold plate showing the motif of the Akanthian tetradrachms. Photograph: KW.

Equally intriguing was a gold plate showing a relief with a lion slaying a bull. Tetradrachms from Akanthos may well have served as a model here, too.

Coin replicas of pieces from Alpha Bank. Photograph: KW.

The coins weren’t that thrilling. Better were the silver painted plaster casts of pieces from the Alpha Bank Collection.

Curse tablet, pierced by a nail. Photograph: KW.

The curse tablets were more interesting. One was there on display which was still in the state the magician had buried it: pierced by a nail. Such curse tablets were used to harm loathsome persons. Their names were inscribed on the lead and buried, in close proximity to a grave, a place where executions were carried out or a battlefield. The underlying idea was that in those areas deceased people rested who had become the victims of violence and whose spirits were mad after harming a human being. And when they were handed such a victim on a silver platter, or rather a lead tablet…

Collector Ioannis Lambropoulos. Photograph: KW.

An entire room was devoted to the collection of lawyer Ioannis Lambropoulos.The high-ranking civil servant, as commissioner for Chalkidike, had assembled an impressive collection until his death in 1972 which Herakles Lambropoulos, son of the collector, had given the Ministry for Culture as a present under the condition that the collection had to be displayed in a section of its own on the museum of Polygyros. Since 2004, at least an exhibition of some highlights can be viewed in a room.

Helmet from the Lambropoulos Collection. Photograph: KW.

Ceramics, jewellery, items made of metal, parts of armor. It is impressive to see what the collector was able to assemble.

By that, we had enough of antiquity. The beautiful blue sea and the shady terrace made it hard for us to focus on the archaeological finds.

Day 23, July 3, 2011, About Xerxes, tourists and the city of Akanthos

Until the present day, it is forbidden for women to visit Mount Athos. Even male tourists have to accept considerable trouble upon entering the republic of the monks. And a good thing, too! After we witnessed in other monasteries some tourists having real problems with sticking to basic decorum in dealing with clerical institutions, it is almost pleasing to know that there are still some places in the world where mass tourism has no business.

To skim off the revenues generated by the fame of the Mount Athos nevertheless, clever entrepreneurs offer boat excursions round the forbidden Athos which have become a real crowd puller.

Boat full of tourists returning from the trip round Mount Athos. Photograph: KW.)

As a result, the once so idyllic fisherman’s village of Ouranopolis not only became the starting port for tourist boats but has entirely dedicated itself to tourism with its state-of-the art hotels, folkloric taverns and tacky souvenir shops.

Ouranopolis. Bronze, c. 300-250. Star with eight radiates. Rev. Aphrodite Ourania. From auction Gorny & Mosch 160 (2007), 1227.

If the location of present-day Ouranopolis is identical to the ancient one? No idea, there is no excavation in the vicinity and no information available in the guidebooks. Ouranopolis in any case is connected with a romantic tale about the younger brother of the Macedonian general Kassandros. It was said that he had been a teacher and founded Ouranopolis as a celestial city where he ruled as Helios around 316. Legend has it that he introduced a special language all subjects were obliged to speak.

Byzantine guard tower of Ouranopolis. Photograph: KW.

Be that as it may. Today, the only visible testimony of the past is a Byzantine fortified tower that was erected in 1344 as guard station against the invading Franks.

Old German trucks are in use for some more time in Greece. Photograph: KW.

Don’t be surprised about the truck’s label. Naturally there is no Schwalbenhof (swallow yard) in the Kornfeld (corn field). But the Greeks like to buy from us our old, discarded (and cheap) cars and see no reason why they should change the paint.

Funny quiz of the week: what technical marvel from ancient times do you see here? Photograph: KW.

Who likes to return to the mainland crosses one of technical marvel of antiquity.

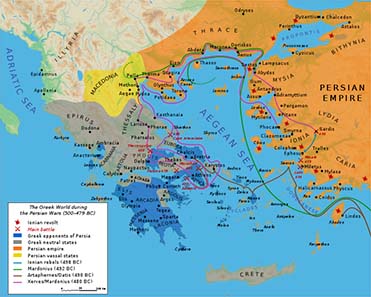

Map of Greece at the times of the Persian Wars. Bibi Saint-Pol / Wikipedia.

In preparation of his second campaign against the Greeks, Xerxes I had a canal built through the Isthmus of the Athos because a major part of the fleet failed there in 492.

“Site of Historical Importance”. Photograph: KW.

Were it not for the signs nobody would believe that there existed such an important structure here once.

Site plan of the Isthmus of Athos. Photograph: KW.

Nearby, at the canal of Xerxes, Akanthos is situated or rather what is left thereof.

Akanthos. Tetradrachm, 530-480. Lion slaying a bull. Rev. Quadratum incusum. From auction Künker 104 (2005), 148.

The pieces from Akanthos range amongst the most impressive coins Northern Greek coinages have to offer – the paws of the lion with which it hits the flank of the collapsing bull, the mane rustled up, the composition fitting so well the coin’s round shape…

All that tells of a powerful city that served the Persians as important base in the war against the Greeks. Akanthos paid 3 talents (= 18,000 drachmai) toll to the Delian League. It survived the conquest of Philipp, the Romans, Christianity…

Remains of ancient Akanthos. Photograph: KW.

This is everything left to see of ancient Akanthos today.

Excavation site. Photograph: KW.

There is a signpost pointing the way via bumpy roads to the excavation site surrounded by a fence trampled down. We were deeply worried about our car every time we got into one of the deep road holes. Finally we arrived at the site. It was protected by a corrugated iron roof and was situated in the midst of stables with chicken, ducks and geese.

Archaeological finds from 2008. Photograph: KW.

It seems that excavations were conducted not long ago. Sherds labeled 2008 are lying on several brittle wooden racks.

Carefully labeled bags with soil. Photograph: KW.

Everywhere dozen of blue bags are lying around, carefully labeled, filled with soil. The excavators surely had planned something to do with them. Whatever that may be, it can’t be done anymore. The plastic material is decomposed and the earth in the bags has become a giant rubbish heap.

That made us sick and tired of it all. It simply hurts to realize that reality doesn’t match one’s dream of an important mint at all.

We got back to our hotel, the blue sea, the little fish and octopuses and to our books were antiquity appears so much more beautiful than in real life.

For next time, however, I can promise you at least one marvelous excavation in undisturbed Thrace. Don’t miss the next issue that takes us to Northern Greek Neapolis, to Mesembria, Maroneia and Abdera.

You can read all other parts of this diary here.