translated by Annika Backe

If we think of Sicily today, we mainly see the island. But neither in the ancient world nor in the Middle Ages, the Strait of Messina was considered a border.

Italian peninsula with Sicily. Source: NASA / Wikipedia.

Let’s not forget that the Greeks rarely built any roads across the mainland. It was the ship, not the wagon, that constituted their most important means of transport. And the famous streets of the Romans that had begun to decay during the Migration Period were poorly restored only in the late Middle Ages. An extensive road network only dates to the early days of industrialization; and the tourists who visited Naples in the 19th century were thrilled to see a ship connection between Genoa and Naples established that saved them the tedious route by land. Together with Southern Italy, the island of Sicily formed a unit, in terms of culture, geography, political matters, and economy. In this series, we will therefore treat it as such.

Map of ancient Magna Graecia. Source: Captain Blood / CC BY-SA 3.0

The wealth of the country

Again and again, people from all over the Mediterranean region came to participate in the riches of Lower Italy and Sicily. And so the native population merged with immigrants from Italy, Greece, Asia Minor, and Carthage in Africa. The Southern part of Italy retained its Greek character even under Roman rule.

Sicily was thus a melting pot of cultures already in ancient times. The reason for this lay in its geography and its mountainous landscape. While the coasts offered easily accessible ports with a fertile hinterland, there were up-country hideaways that were almost impossible to take. Inaccessible mountain villages were a safe haven for defeated peoples for centuries. This is where the Elymians survived the Carthaginian conquest. This is where the Byzantines held their fortresses against the Arabs for decades. This is where the Arabs stayed when the Normans conquered the island.

Gela. Tetradrachm, 420-415. Rv. Protome of a river deity in the shape of a bull with a human head. From Gorny & Mosch sale 244 (2017), 56. – Rich in water, the island of Sicily developed the idea of a river deity who granted rich crops just as much as he flooded the city with his water masses..

But what made the country so incredibly attractive to foreign settlers? Well, right into early modern times, it offered two advantages: Firstly, it was extraordinarily fertile. Supplying the various rivers with sufficient water, the alluvial plains yielded large quantities of grain. Frederick II became rich and powerful through successfully monopolizing the grain trade of Sicily, Central and Upper Italy.

And this takes us right to the second advantage of Sicily’s. Its central location and protected harbors made it an excellent starting point for merchants. There, goods from the whole Mediterranean region were resold. The profit made the people rich.

Wilhelm von Gloeden, Peasant family of Taormina, c. 1880/1885.

But why did Sicily later become the poorhouse of Europe? It’s quite simple: The time of the small, naturally fertile, hand-picked fields came to an end when huge plants were artificially fertilized and built on a grand scale in the New World. No matter how fertile the lands, no natural farming can keep up with that.

Furthermore, the trade also looked for new ways and means of transport. Nowadays, Sicily is no longer at the center of a thriving Mediterranean economy. Rather, it has become a European frontier fortress, where the rich countries rigorously defend themselves against the invaders from impoverished Africa.

Byzantine Emperor Justinian next to his court officials. Mosaic from San Vitale / Ravenna. Source: Wikipedia.

Byzantine Sicily

In 533, a fleet of 500 ships left Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. It carried 15,000 infantry and horsemen who had received Justinian’s order to recapture rich Sicily.

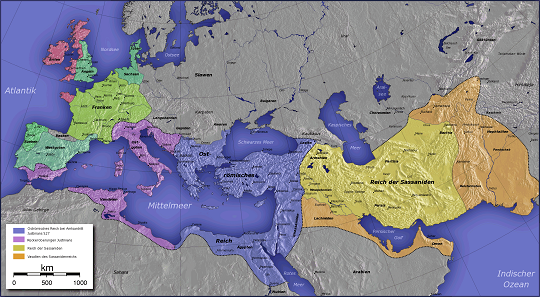

Justinian’s conquests. Source: Captain Blood / CC BY-SA 3.0

Sicily was only the beginning. Justinian intended to reunite the entire Roman Empire in one hand. With its favorable strategic location, the island was planned to serve as a supply base during the attempt to free Italy from the hands of the Germanic tribes. As a matter of fact, the army didn’t meet any significant resistance: The Vandals disappeared, and the Byzantine Empire established itself in Sicily and Lower Italy.

The population probably welcomed this change of power. These territories had been in Greek hands as early as the 7th century colonization after all. The South disagreed and greeted the Byzantines, for people found it easy to understand their culture. Greek was the language of the population, and in matters of religion Constantinople served as a point of reference. Sicily and Lower Italy remained an essential part of Eastern Rome for nearly 200 years, although the lion-share of Justinian’s other conquests was lost as quickly as they had been made.

Constans II (641-668) with Constantine IV. Solidus, Syracuse. From Gorny & Mosch sale 244 (2017), 634.

Capital of the Byzantine Empire

The Southern part of Italy was still so important to the Byzantine rulers that, in 660, Emperor Constans II made the curious decision to move the capital of his empire from Constantinople to Syracuse. We can only speculate about his motives for doing so. The emperor had made himself so unpopular that hostile tradition masks what had really happened. We know that under Constans the Eastern Empire was under heavy attack by the expanding Arabs.

Constans II (641-668). Follis, Syracuse. From CNG, Triton sale 8 (2005), 1383.

Armenia and Cyprus were lost to the Byzantine Empire under his rule. And the naval victory of the Muslems at Phoenix in 655 proved the Arab fleet to be finally superior also to the Byzantine ships. Perhaps it was this situation that prompted the emperor to decide to give up the East to protect the possessions of the West. For the West, too, was threatened to be conquered. In 652, Arab ships had already reached Sicily and destroyed Syracuse.

The ancient temple of Athena in Syracuse, which was then converted into a church. The beginning of the construction work might well be related to the reign of Constans in Syracuse. Photo: KW.

Constans went to the West with a large army. Rome was no longer a suitable headquarters. Although the Pope greeted the emperor kindly, he certainly made it clear to him that he was not ready to share power in his papal state. And so Constans chose Syracuse as a base of operations. He thought this rich city most likely to become the target of a Muslim attack.

Constans II (641-668). Semissis, Syracuse. From CNG, Triton sale 13 (2010), 1666.

The imperial burden put a strain on the population of Sicily. After all, not only an army but the entire court, including all its officials, had to be supported. The exploitation by the imperial tax collectors is said to have plunged the farmers into ruin. Since the chroniclers of this era didn’t like Constans, the question is whether or not their allegations are justified. They relate that husbands sold themselves as slaves and sent their wives into prostitution, to be able to pay the taxes. May be this is an exaggeration. What is certain, however, is that the tax burdens rose to unprecedented heights after the emperor’s arrival. So it was probably a relief to the ordinary people when a Greek servant killed the great emperor with a soap dish in the bath.

Through tax collectors of Emperor Constans, the Byzantine rule had become so unpopular with Sicily that a rebellion broke out. This was immediately suppressed by the emperor’s successor, who then relocated his seat of government to Constantinople again, and stationed only a large army in the fortresses of Lower Italy and Sicily to secure the country against an Arab conquest.

The imperial burden put a strain on the population of Sicily. After all, not only an army but the entire court, including all its officials, had to be supported. The exploitation by the imperial tax collectors is said to have plunged the farmers into ruin. Since the chroniclers of this era didn’t like Constans, the question is whether or not their allegations are justified. They relate that husbands sold themselves as slaves and sent their wives into prostitution, to be able to pay the taxes. May be this is an exaggeration. What is certain, however, is that the tax burdens rose to unprecedented heights after the emperor’s arrival. So it was probably a relief to the ordinary people when a Greek servant killed the great emperor with a soap dish in the bath.

Through tax collectors of Emperor Constans, the Byzantine rule had become so unpopular with Sicily that a rebellion broke out. This was immediately suppressed by the emperor’s successor, who then relocated his seat of government to Constantinople again, and stationed only a large army in the fortresses of Lower Italy and Sicily to secure the country against an Arab conquest.

Leo III (717-741). Solidus, Syracuse. From Gorny & Mosch sale 170 (2008), 3075.

The army at this fortress was still paid with Byzantine solidi, some of which were minted in Sicily.

The time that followed was comparatively peaceful. The local people adjusted. Apparently, Arab merchants attended to their business undisturbedly in Sicily as early as the beginning of the 9th century. And in 805, a Byzantine governor of Sicily signed a treaty with the Aghlabid ruler of Tunis – without even asking the emperor in Constantinople for his permission.

In the next episode, you can read how the Arabs conquered Sicily.

All parts of this series can be found here.

As for Sicily’s history in ancient times you can read our series “Sicilian Mosaic”.

And if you want to see more pictures of Sicily, we recommend our ‘Sicily in full bloom’ series.