by Ursula Kampmann

Translated by Leonie Schulze

September 13, 2018 – The abbreviation DAMIN stands for Dépréciation de l’Argent Monétaire et Relations International, which translates to Silver Monetary Depreciation and International Relations. This title denotes a phenomenon of the second half of the 19th century. Due to a large number of silver finds and a dramatically decreasing demand, the price of silver hit rock bottom during that era. This development had a decisive effect on all those states that did not convert their currency to the gold standard as did the German Empire for example. Countries such as India and China suddenly had to pay much higher prices for imported goods due to their silver-based currencies, which is why they more or less ceased to be buyers of Western industrial products. It is likely that the immense pressure put on the export-oriented industries of the Western world was the decisive trigger of the ever-increasing rivalry between Germany, Great Britain, and France.

The participants of this year’s DAMIN Congress. Photo: UK.

Among other things, official documents regarding the fiscal decisions of as many countries as possible are edited within the framework of the DAMIN Project in order to get a better understanding of the actual global effects. And congresses are held regularly. These do not only deal with the 19th century. They address the topics of mining, trading of precious metals, and minting covering many time periods and regions. The idea is that this approach offers the possibility to think outside the box and thus possibly come up with new ideas. Part of this concept is that the participants reflect this internationality as well. 12 speakers from 10 nations met up and presented their latest research.

Ivar Leimus (l.), organizer of this congress, and Georges Depeyrot (r.), initiator and head of DAMIN. Photo: UK.

The funding of DAMIN ends in 2018. Therefore, the Tallinn Congress held from the 5th to the 7th of September 2018 was the last one under this label. Ivar Leimus, researcher and curator at the Estonian History Museum, organized it excellently, which made it possible for the participants to have discussions and learn from each other in a comfortable atmosphere. In the following, we are going to summarize the covered topics.

Christophe Flament (l.) speaking in the banqueting hall of the Great Guild. The session was presided by Jürgen Nautz (r.). Photo: UK.

The congress began with what could be called a scholarly sensation. Christophe Flament postulated very convincingly that the Athens mint did not primarily produce coins on behalf of the state but private investors, mainly the tenants of the mines in Laurion, who brought their raw silver to the mint and paid it to strike coins. They then used these coins to cover their extraordinarily high expenses.

The amount of coinage should therefore not be seen in correlation with war but as being connected to the annual revenue of the silver mines.

Part of the sightseeing program was a visit to the Cog, which was just excavated in 2017.

After a talk on Roman coin finds in the Ukraine and Moldavia, which presented a completely different structure than the hoards of the Roman Empire demonstrating that these coins were not used as circulation money but were more of a status symbol of some generals, the next presentation initiated the Early Middle Ages. Ivar Leimus dealt with the origin of Baltic coins and demonstrated how the sources had changed over the course of 300 years. First, the money came from the Harz Mountains, then from Britain and, in the 13th century, from Saxony. In connection with this, Ivar Leimus posed the provocative question of whether these silver coins did not also finance the Christianization of the Baltic region.

Roman Zaoral provided an overview of the history of coins in Bohemia. Photo: UK.

Two talks addressed the monetary situation in Bohemia. Roman Zaoral, professor at the Charles University in Prague, traced the history of coins in Bohemia, which was one of the most important manufacturers of silver in Europe during the High and Late Middle Ages. His detailed presentation illustrated the decisive economic importance of Bohemia at that time. Pawel Milejski dealt with Prague groschen from Polish and Lithuanian hoards. He traced the coins’ decrease in fineness and weight under the reign of Wenzel IV (1378-1419).

Lodging was provided at the monastery of the Bridgettine Order in Pirita, a few miles outside of Tallinn. Photo: UK.

Claudia Jefferies’ talk took the participants from Europe to the New World, from the Late Middle Ages to the dawn of the modern period. She analyzed letters that referred to the economic problems of mine owners in Zacatecas, who had to accept large setbacks in profit between 1550 and 1620. They attempted in vain to pass on parts of their losses to dealers who exchanged their raw silver for the money they needed to cover the running expenses of their mines.

Viktors Dabolins (l.) talks about Riga. Ivar Leimus (r.) presides the session. Photo: UK.

A return to Europe in the year of 1621 was initiated by Viktors Dabolins’ presentation. In said year, Swedish troops under Gustav Adolph conquered the city of Riga. The king’s initial attempt to incorporate the municipal mint into the Swedish monetary system failed. The events of that year are excellently documented in various archival sources. The Riga example could have been important for the entire coinage of the German Empire as it is possible that what occurred in this important commercial city convinced Gustav Adolph to change his policies and allow the local monetary system to remain intact so as not to further burden the economy.

A visit to the ruins of Pirita Convent. From left to right: Roman Zaoral, Claudia Jefferies und Claudio Marsilio. Photo: UK.

Claudio Marsilio provided an exciting insight into the world of Italian bankers of the emerging modern period. Ever since the end of the 16th century, those bankers met in Piacenza, Novi, Verona or Bolzano to buy and sell letters of credit from all over the world. The “currency” in this international trade was virtual. It was called “scudo di marco”. It served as the basis of a sort of “fixing” of those letters’ prices, which were defined on the third day of the meetings. Lists of these prices circulated among bankers all over Europe and, as a type of precursor of the Financial Times, their prices constituted the basis of the trading of letters of credit.

Jürgen Nautz and Karin Schneider talked about the financing of the war debts France had to pay after the Napoleonic Wars. Within three years, between 1815 and 1818, they were paid off completely, mainly in order to end the British occupation, the expenses of which had to be covered by France. Despite drastic losses of harvest after the year without summer, the money market was booming. With very modern-seeming measures, the French government had succeeded in mobilizing banks and convincing European investors of the stability of French state bonds.

Simon Bytheway, professor at Nihon University in Tokyo, contributed a presentation on Japan. He asked where from and how Japan had obtained the gold it used to finance its modernization or, put more plainly, its “Westernization”. Based on the booming trading of tea and silk, they succeeded in obtaining enough gold to pay for weapons, war vessels, railways and more. The largest part of this gold did not come from Great Britain, as one could assume, but instead from the United States of America.

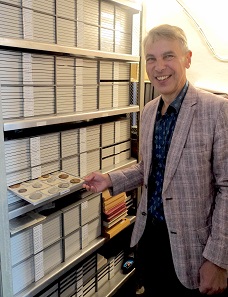

You will soon read an article about the numismatic treasures Tallinn has to offer. Ivar Leimus gave us a small glimpse of the collection. Photo: UK.

Ursula Kampmann concluded the congress with a talk on a contemporary topic. Using the commemorative coins of 2011, she asked whether the organizational structures of mints had an influence on the design of said coins. There is, in fact, an influence, but it is not a decisive one. As soon as a mint acts as a profit center its production is primarily market-oriented. The design of coins is then additionally determined by the type and extent of control a governmental institution has on the coins and their designs.

As always, the discussions that followed each and every presentation were lively and lead in a very friendly manner. The excellently organized accompanying program did not only offer a vast insight into everything there is to see in Tallinn but it also enabled participants to continue discussions about many of the congress’s topics in smaller groups.

All of the participants regret that this is the last DAMIN meeting. Although it does seem possible that there might be a follow-up project. The personal friendships built over the years will in any case survive the end of the project.

Because congresses are really just the tip of the iceberg, a short and wonderful highlight which allows for a refreshing of the numerous connections between scholars. Just like economic history, numismatics too depends on the existence of these relations, as the big picture cannot be drawn by a single person. Instead, many people have to bring together their small puzzle pieces in order to collectively reconstruct the panorama of the development of our money. And only if we are aware of the puzzle pieces of others we can adapt our own research accordingly so that our puzzle pieces fit in seamlessly.

The conference proceedings will be published in December of 2018. The book went in print on Monday, September 10, 2018, four days after the conference had ended.

We have already presented the DAMIN project in detail.

More information on the project can be obtained from the DAMIN website.

A content summary of all presentations is available on the DAMIN website.

If you are interested in previous DAMIN congresses: in 2015, the focus of the Copenhagen congress lay on mints, in California in 2017 it lay on mining.

By the way within one of our next issues we will report on the numismatic side of Talinn in detail.