by Ursula Kampmann

February 22, 2012 – Only a few images stick to your mind so powerfully as the huge heads of the broken monumental statues of Nemrut Dag. During our trip there, however, we have seen many other things: marvelous rocky landscapes, a magnificent bridge from Roman Times and lots of friendly people.

June 22, 2009

There are numerous travel agencies in Urfa that always wait for tourists wanting to visit Nemrut Dag. We, too, had found one and booked the entire tour for the following day because the local tour guides didn’t offer anything simple as a trip to Nemrut Dag only. We weren’t given any choice but had to visit every single attraction on the way there in order to stand on Nemrut in time, high above the rest of the world, to watch the sun setting.

Yussuf shows us his native country – with a good pinch of humor. Photograph: KW.

Our driver Yussuf fetched us at 9 a.m. sharp. On our way we took several breaks to marvel at the different plants. We passed endless plantations where pistachios were cultivated. We were informed that a pistachio tree needs roughly 30 years to produce heavy crops. We saw grape crops – not wine grapes but table grapes. They look nothing like our vine stocks since they are not pruned but grow as bushes near the ground.

Chickpeas right from the shell. A real tidbid. Photograph: KW.

Particularly delicious were the chickpeas one can pick from the bush and eat on the spot.

At the dam of the Atatürk Dam. Photograph: KW.

Our first station was Lake Atatürk. We are familiar with the enormous project, of which this construction is part of, mainly because some important ancient excavations fell victim to it. A case in point is Samosata, place of residence of the Kings of Commagene, but perhaps even better known as place of birth of the satirist Lukian.

Gallienus. Antoninian, Samosata, 255-256. Rev. Gallienus and Valerian performing a sacrifice. RIC 446. From auction Gorny & Mosch 186 (2010), 2241.

Samosata continued to be an important place until Late Antique Times. Legio VI Ferrata as well as Legio XVI Flavia Firma was stationed at this crossroads with its military significance. It was here where Iulianus had his fleet built which he sent up the Euphrates River to fight the Sassanids. We don’t know what had sunken in Samosata. The gorgeous mosaics from Zeugma we have marveled at in Gaziantep, however, might give a hint. By the way, Zeugma didn’t fell victim to the Atatürk Dam but to a second dam located further to the west.

The system of 22 dams and 19 hydroelectric power plants aims to collect the great amounts of melt water flowing from the mountains in the spring and to use it to convert the region into a thriving garden. The project is called GAP, an abbreviation for Güneydogu Anadolu Projesi (= Southeastern Anatolia Project) and has turned the former dust deserts into thriving gardens. Cities like Gaziantep and Urfa really have seen quite a boost as a result. Agricultural produce has multiplied. It is arguable whether this development is of long continuance or if the critics will be proven right arguing that the artificial watering emaciated the soil and caused erosion and poor harvests. It comes as no surprise that the neighboring countries, which depend on the water from Euphrates and Tigris, are highly skeptical towards the ongoing project.

Monument for the builders of the dam. Photograph: UK.

Anyway, we sat down in a tea room close by the dam, looked at the blue water of the Euphrates (or rather, we looked at what was left of it after damming it) and read the motto of Atatürk written on the dam in capital letters: Ne mutlu Türkum diyene – Happy is he who calls himself a Turk. Our Yussuf told us quite a few things – although I have to take these numbers from my smart book: the reservoir contains 800 square kilometers at maximum. It is possible to water 882,000 hectare ground. Since the dam was completed in 1995, the yields of the fields watered have tripled.

Big toe in chilly Euphrates. Photograph: KW.

Our next stop was Euphrates River. After all, in my note to my customers about my vacation I had written that I had travelled to the remotest corner of Turkey to dip my big toe in Euphrates. And that was precisely what I did – while the present village youth had a good laugh. By the way, the water was cold as ice!

Column with eagle in front of tumulus. Photograph: KW.

Around noon we had reached our first destination, Karakush, a sepulchral monument King Mithradates II of Commagene had erected for his mother and other female members of the royal family. The burial chamber that must have existed at some point is said to have been plundered already in the 1st cent. A. D. We stood in front of a huge tumulus that was surrounded by a few tall columns. The one preserved best showed an eagle. Even more spectacular, however, was the view!

Roman bridge. Photograph: KW.

Next stop was at Cendere Bridge, a bridge built in Roman Times, more specific under Septimius Severus. Camels and donkeys, humans and cars have passed it, until some day a gas truck drove over it which proved to be too heavy. The bridge collapsed; it was restored; today, only pedestrians are permitted to walk on it. Of the once four columns for emperor, empress and the two sons of theirs only three are still standing. The one for Geta fell victim to the damnatio memoriae.

In 30 years from now, when remembering this bridge, I will surely recall one thing about my visit: the heat. It was half past two, the hottest time. I retreated into the shade and was invited to have a tea. I had a nice talk with my host. He asked me how many children I had. I played along and spoke with pride of my four sons (“all of them pilots with Swiss Air”). He nearly died of awe. He was very nice, but, all the same, what mindscape is that where a woman can only be proud of her sons and her own achievements count for nothing!

Mamluk fortress Yeni-Kale. Photograph: UK.

Afterwards we proceeded to Yeni-Kale, the ruins of a fortress built in the 13th century. German archaeologist Friedrich Karl Dörner wrote about it and discovered a station for carrier pigeons there which could have been used for communication. In the past, it was a 6 to 7 hours walk, via rough paths, from Yeni-Kale to Nemrut Dag. Today, being paying customers, we went on strike when Yussuf suggested to go rambling to the ruin, via a steep rocky stairway.

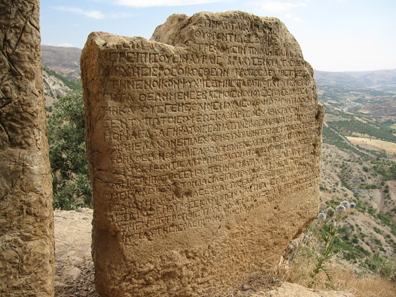

An inscription with a presumably very fascinating content. Photograph: KW.

It was hot. Everything was sticky, but the tour went on, to the summer residence of the Kings of Cappadocia, to Arsameia. I have to admit that it really took it out on me by then. When even we only wanted to get some shade and water, how boring must these old stones be to those people who aren’t interested in ancient times! Plus, there was no information on the spot available which could have filled the things seen with a bit of life. Yussuf kept on jogging but I for my part only wanted to descent. The view was incredible, yes, but I would have liked water and shade better!

Entrance to a tunnel in a wall of rock full of inscriptions. Photograph: KW.

Arsameia on the Nymphaios was founded in the 3rd cent. by Arsames and was named after him. Seleucid Antiochus Hierax allegedly fled here in 235 B. C. during the conflict with Seleucus II. The place is famous mainly for its burial precinct Antiochus I had built for his father, Mithridates I, ruler of Commagene.

A king of Commagene (Mithridates or Antiochus) clasping hands with Heracles. Photograph: UK.

A processional route leads the way past numerous stelae of which the one showing the dexiosis between a king of Commagene (the deceased or the builder of the tomb?) is preserved best.

The road to Mount Nemrut. Photograph: KW.

At last, we had finished our obligatory program and, around 4 p.m. the main destination of our journey came in sight: we headed for Mount Nemrut, driving steep, sometimes only scarcely surfaced roads. Good thing was that the car had enough horse power. So we got along slowly but steadily in the breathtaking landscape. Dull vegetation, secludedness, and a small village from time to time, we drove for more than one hour before we finally arrived. It had become chilly, so chilly that we could really use our windbreakers. I enjoyed putting on this bulky piece of cloth for once that refuses unwaveringly to fit in my suitcase every time I go on a journey.

It took roughly 20 minutes to walk from the parking site, uphill on steep paths. This is nothing for elderly or overweight people, that’s for sure. It is hard to imagine that roughly one quarter of a million visitors come to Nemrut every year. You see, a visit is only possible for a couple of months a year. Until mid-May the road can be snow-covered. Nevertheless, most people come here in May, there are hordes of Italians in August, masses of people come between September and mid-October before Mount Nemrut is buried in snow again. Even so, we mustn’t complain. Approximately 50 visitors had come for the sunset, it is said that it’s going to be 2,000 to 3,000 in May.

Arsames I, before 130 A. D. Bronze. From auction Gorny & Mosch 159 (2007), 239.

By the way, the empire of Commagene with its capital Samosata is already mentioned in Assyrian texts. It is said that it used to be its ally until Sargon II incorporated the area as province into his big empire. Most probably the Persians conquered the mountainous region, after them Alexander, and around 200 B. C. Antiochus III called himself King of Commagene. The Seleucid supremacy came to an end with the death of Antiochus IV Epiphanes in 163 B. C. The central power declined and Ptolemaeus, Satrap of Commagene, succeeded as autonomous ruler. Ptolemaeus was of Parthian origin. His successors, however, eyed west. Consequently, Mithridates I (100-70), the very king the sanctuary of Arsameia was dedicated to, married a Syrian princess, Laodice VII Thea.

Antiochus I, c. 69-34. Bronze. Rev. pacing lion. From auction Gorny & Mosch 199 (2011), 527.

Their son, Antiochus I Theos of Commagene (70-38) was to become greatest king of the empire. It was he who erected the great sanctuary on Mount Nemrut. He stood on the Roman side when Pompey fought against Mithridates of Pontos and therewith secured Commagene its autonomy. Only when Antiochus III died in 17, the territory fell to the Romans even though there had been an heir to the throne.

Tiberius, 14-37. Dupondius, mint in Commagene. Rev. wingeld caduceus. RIC 89. From auction Gorny & Mosch 164 (2008), 367.

Tiberius annexed the empire and affiliated it to the Province of Syria.

Antiochus IV, 38-72. Bronze. Rev. scorpion. From auction Gorny & Mosch 196 (2011), 2270.

Caligula reinstated his son Antiochus IV, whom he had met frequently at the court of his grandmother, as autonomous king and added rough Cilicia to his empire. It was Claudius, though, who made sure that this appointment was carried out. Antiochus was a loyal ally of the Romans in his empire. He levied an army for Nero to make war on the Persians and was made ruler of Armenia for a short period of time as a reward. Vespasian, who had relied on the money and the troops of Antiochus when he ascended to the Imperial throne, deprived him of his empire in 72 because the governor of Syria accused its neighbor to collude with the Parthians.

Antiochus IV for his sons Epiphanes and Callinicus. From auction Künker 94 (2004), 1384.

Actually, his sons fled to the Parthians whereas Antiochus retreated to Sparta first and retired in Rome later on. We don’t know exactly when he died but henceforth Commagene was an integral part of the Roman Empire.

Head of the colossal statue of Mithras. Photograph: UK.

What can I say about Mount Nemrut? In all probability, everyone has already seen pictures of this impressive monumental tomb site.

The tumulus. Photograph: UK.

In front of a huge tumulus there lie the fractured bodies of the figures representing deities. The heads lie in front of them. Actually, the site is rather small and manageable. The most impressive thing is the lack of any touristic infrastructure. There are a few small tea stands near the entrance, plus one or two souvenir shops, a yellow information board with a ten-line English explanation and that was it.

Further colossal heads. Photograph: UK.

So we had a look at the East terrace first, then at the West terrace. And that was about it. I sat down to enjoy the view at the West terrace and, most of all, the wonderful vista.

Everyone is waiting for the sunset. Photograph: KW.

Everyone stood there waiting for the sunset. We decided to skip it. Famous sunset, all very fine, but standing there together with 50 people peering West, mesmerized, to moan ‘wow’ in the right moment – no, that wasn’t our cup of tea. Especially when considering our way back, the rather steep and uncomfortable path downhill, then in the dark… It was, however, a bit of a problem to make our decision clear to Yussuf. He simply didn’t understand what we meant. Missing the sunset was beyond his conception of the world. A Turk came to our rescue, translated, and we got talking. It so happened that we had met the director of tourism of neighboring Adiyaman who was on an on-site visit on Mount Nemrut with a commission to consult on the excavation’s expansion. The following hour was most interesting. We talked shop about the various possibilities – from an exhibition room with digital presentation to audio guides and explanatory boards. It was invigorating. Quite some time later I realized that for once a Turk had talked with me on an equal footing again. The women’s standing here in the East is something I have real issues with.

Anyway, we were amongst the first leaving. In retrospect, we were glad that we had done so because we weren’t home until a quarter past eleven – even though we skipped dinner which Yussuf proudly described as inclusive.

The drive in the mountains was highly impressive. The one thing I surely won’t forget, however, were the burning fields we passed. In Turkey, they still burn the harvest remains to secure the fertilization of the next sowing. That is not very eco-friendly and it is almost spooky to watch the fires flickering along the road in the pitch-black night.

The next issue of the numismatic diary is devoted to Urfa and Caesarea Cappadocia, the important administrative center at the foot of Mons Argaios.

You can read all other parts of this diary here.