Egypt and Alexandria. A brief numismatic survey: part IV

Cruel Caracalla?

Caracalla, the son of Septimius Severus, was to visit Alexandria under much less favorable conditions than his father. The Alexandrinians, on the other hand, were looking forward to his visit that was scheduled for the year 215. After all, they knew Caracalla from his childhood on. He had accompanied his father when he had traveled the country. Caracalla’s entry was celebrated with pomp and circumstance:

Caracalla, 198-217. AE, 212/3. Rev. emperor as military commander, wreathed by Sarapis. CNG 12 (1990), 287.

“[Caracalla] therefore ordered a number of hecatombs of cattle to be prepared, together with offerings of every kind. When these matters were reported to the people of Alexandria, who are by nature carefree and very easily aroused on the slightest provocation, they were overjoyed to learn of the emperor’s enthusiastic interest and his great affection for them. They prepared a superlative reception for the emperor. Everywhere bands were performing on all kinds of musical instruments and playing a variety of melodies. Billows of perfume and the smoke of incense spread sweet aromas throughout the city. The emperor was honored with torchlight parades and showers of floral bouquets. When he entered the city, accompanied by his entire army, Caracalla went first into the temple [of Sarapis], where he sacrificed many hecatombs of cattle and heaped the altars with frankincense. Leaving the temple for the tomb of Alexander, he removed there his purple robe, his finger rings set with precious gems, together with his belts and anything else of value on his person, and placed them upon the tomb.” (Herodian 4.8.7-9).

Artabanos IV, A. D. 80-90. Drachm, Ecbatana. From auction sale Gorny & Mosch – Stuttgart 1 (2010), 298.

The Alexandrinians just liked to revel. The appreciated much less another plan of the emperor: Caracalla concentrated his troops for the great military campaign against the Parthians. He considered himself successor of Alexander and the one who was to defeat the empire in the east. He would have been only too pleased to see some descendants of the Macedonians amongst his ranks who, as far as he knew, had once colonized the Ptolemaic Empire. But the Alexandrinians of Caracalla’s days had nothing in common with the belligerent Macedonians of the past, quite the contrary: they fled from being recruited, even knocked some statues of the emperor down. With an imperial army being present in the city, that is always a bad idea.

Bust of Caracalla. Pergamon Museum, Berlin. Photograph: UK.

Caracalla sent for the magistrates – after all, since Septimius Severus the city had a politically responsible city council – and punished them in place of their fellow citizens. That caused further disturbances and so on and so forth, until it came to the notorious bloodbath that ancient authors describe with such relish in order to illustrate the cruelty of Caracalla: “Then he betook himself to Alexandria, and here he called the people together into the gymnasium and heaped abuse on them; he gave orders, moreover, that those who were physically qualified should be enrolled for military service. But those whom he enrolled he put to death …. In addition to this, he issued an order to his soldiers to slay their hosts and thus caused great slaughter at Alexandria.” (Historia Augusta, Caracalla 6.2-3)

Anyhow, the revolt was crushed. Caracalla issued special regulations to prevent such upheavals in the future. One such regulation forbade any spectacles and public banquets since they drew too big a crowd and hence provided a hotbed for riots. Additionally, the emperor divided the city into different districts, which were easier to control, by building several walls. Not forgetting, after his visit, no further Alexandrinian coin left the mint, at least not as long as he was in power. It was Macrinus under whose reign the coining slowly started again.

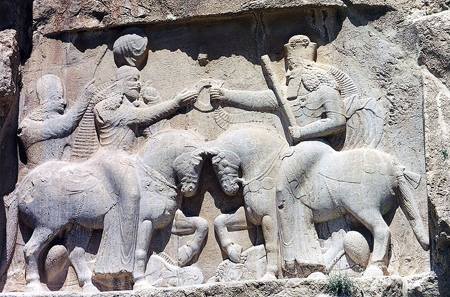

Ardashir I is given the ring of power by Ahura Mazda. Rock relief of Naqsh-e-Rostam. Photograph: Ginolerhino / http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

Fresh start with Roman help

In the 220s, the Sassanid Ardashir I defeated the Parthians, the old enemy of the Roman Empire, and founded his own empire that pursued a much more aggressive foreign policy than his predecessors had ever done. Certainly, Rome soon realized that another quarrel was imminent in the east. In order to make the necessary logistic preparations, the infrastructure had to be brought up to date which also included setting the old mint of Alexandria to work again. The few workers left weren’t able to produce all the coins required to pay the mobilization of Egypt.

Severus Alexander, 222-235. Tetradrachm, 224/5, Alexandria Mint. Rev. bust of Sarapis r. Blancon, list 31 (1999-2000), 344.

That was why, in the years 4, 5 and 7, hence 224/5, 225/6 and 227/8, the Alexandrinian coins were manufactured in Rome and then shipped to Egypt. We can easily tell the Roman tetrachdrachms from the local ones. They exhibit an entirely different style, and the year on the reverse is never abbreviated but always stated in full.

Severus Alexander, 222-235. Tetradrachm, 224/5, Rome Mint. Rev. bust of Sarapis r. Dürr-Michel (1998), 645.

Under the lead of Emperor Severus Alexander, the Romans managed to beat off the Sassanid attack in 232 and 233. Shortly after the assassination of the young emperor in 235, however, the horsemen of Ardashir invaded Mesopotamia again.

A rock relief at Naqsh-e Rostam (Iran) depicts the triumph of Shapur I over the Roman emperor Valerian. Photograph: Fabienkhan / http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/deed.en

The divided city

The Sassanids were to become one of the biggest concerns of Roman foreign policy. The year 260 even witnessed the emperor Valerianus being taken captive after having fought in the east – and he was the first emperor who ever experienced this –, while his son Gallienus held the west.

Macrianus, 260-261. Tetradrachm, 260/1. Rev. eagle standing l. Auctiones 26 (1996), 491. While the Roman imperial coins of Macrianus and Quietus are rather scarce, their coins can be found from time to time amongst the products of the Alexandrinian mint.

Macrianus…

Quietus, 260-261. Tetradrachmon, 260/1. Rv. eagle standing l. Blancon, list 31 (1999-2000), 622.

… and Quietus rose against the latter. They attracted great support in the east. But they didn’t manage to expand their territory into the west as well. Their army was beaten in Thrace in 261. Macrianus was killed in action. Quietus was killed by Septimius Odaenathus of Palmyra, husband of famous Zenobia, when he tried to escape. Their supporters more or less stood with their backs to the wall. A severe punishment by Gallienus was in store for them. No wonder that Mussius Aemilianus, prefect of Egypt, took the bull by its horns. Instead of surrendering unconditionally to Gallienus, he got himself proclaimed emperor.

Gallienus, 253-268. Tetradrachm, 261/2. Rev. eagle with wreath and palm branch standing l. Blancon, list 31 (1999-2000), 542. Although minting went on during the disturbances in Alexandria in 261, the emission is much smaller and the coins of that year are much scarcer than the similarly looking other specimens. In 260/1, only five different coin types were produced, whereas they added up to 18 again in the following year to which our piece dates.

That didn’t agree with Alexandria: Gallienus sent an army that successfully took a part of the city at once. Mussius Aemilianus, on the other hand, managed to hold the Greek Quarter and the vicinity of the palace, which made the famous boulevard of Alexandria become the demarcation line all of a sudden, separating the imperial Roman army from the troops of the Egyptian usurper.

With Dionysius, Bishop of Alexandria, we have a contemporary source that describes the unbearable situation in 261: “For it would be easier for one to go … from the east to the west, than from Alexandria to Alexandria itself. For the very heart of the city is more intricate and impassable than that great and trackless desert which Israel traversed for two generations.” (Eusebius, Church History 7.21.3-4).

At some point before 30th March 262, the Roman central power prevailed. Alexandria was conquered and Mussius Aemilianus killed. Yet another supporter of the crushed pretender to the throne rose up – he was called Memor and had served as high-ranking provincial official under Mussius. But he, too, was wiped out by the central power, which again claimed a high number of victims.

Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra, will be in the focus of the next episode.

You can find the other parts of this series here.

Together with Thomas Ganschow, Ursula Kampmann has written a catalog on the Alexandrinian coins. For ordering it, please click here.