Graspable Testimonies – Testimonies to Piety from Another Time: Part 1

On 16 October, 2014, Gorny & Mosch will auction off the collection of Werner Jaggi (1927-2002) in Munich with auction sale #226. Over the course of several decades, the distinguished expert on religious art mainly of the Alpine region assembled the largest collection of numismatic testimonies on religious beliefs and customs the market has ever seen. After the natural sciences have explained the world to us, we have lost the understanding of the unconditional belief that is expressed in these objects. Hence, only few people can still appreciate what a gnadenpfennig or an amulet may have meant to its wearer back then.

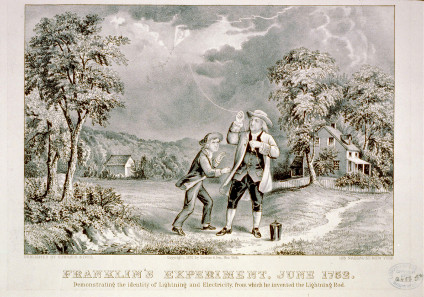

Franklin’s Experiment, June 1752 Demonstrating the identity of Lightning and Electricity, from which he invented the Lightning Rod.

In 1749, Benjamin Franklin constructed the first lightning arrester. In 1859, Charles Darwin published his book “On the Origin of Species”. And in 1876, Robert Koch for the first time described the role bacteria plays in the formation of an illness. Scientists like these explained the world to the modern man, enabled him to at least understand some things, like severe weather or an illness, if not necessarily defeat them. In doing so, they initiated the conception of the world to radically change, leading the way to the modern man which is strongly shaped by the ratio and for whom religion and eschatological beliefs are nothing more than a lifestyle.

Way into the 19th century, all people – craftsmen, peasants and noblemen alike – had felt victim to an unpredictable fate. Life could have been cut short at every second. A thunderstorm destroyed the crop and caused famines. A plague cost the life of the entire family. Help could only be expected from divine entities, security could only be achieved in the Netherworld. The human being was both powerless and defenseless. Naturally, the distressed one looked for a way to do something in this state of emergency. He went on a pilgrimage or pledged a holy trip, a financial donation, in order to have his share in the blessing – and this, by the way, is something not only the Catholics did.

Votive paintings in the Grace Chapel in Altötting. Photograph: Martin Wimmer / http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0

When we today are faced with ‘pilgrimage’ as a term, then the important medieval pilgrimage destinations spring to mind: Jerusalem, Santiago, and Rome. Central to the people in Baroque times, though, were local pilgrimage destinations that were systematically enlarged by the leading figures of the Counter Reformation. Instead of a huge, one of a kind experience, which only a small elite circle amongst the believers could afford, a comprehensive infrastructure was created thanks to which it became possible for the ordinary believer, too, to enjoy a little religious timeout, at some instances a couple of times per year. In Catholic areas we still encounter a dense net of lavishly embellished pilgrimage churches including pictures with miraculous powers as well as an accompanying infrastructure with guest houses and gift shops. Andechs, Ottobeuren and Waldsassen, Mariazell, Maria Taferl and Maria Einsiedeln, Loreto, Montecassino and Subiaco – they all have one thing in common: the centuries-long veneration the believers paid to the divine. Today, thousands of votive pictures in these pilgrimage churches still bear witness to gratitude, danger and rescue.

Another kind of source for this chapter of our cultural history are pendants, amulets, crosses and so on, as they are available for sale as memento and talisman in front of the pilgrimage church in many countries.

These ‘gnadenpfennige’ were produced in large quantities. They were often consecrated explicitly in the context of the service and hence ‘activated’, as it were. Most of them feature the cult image of the pilgrimage. Thanks to their accurate depictions they can be taken as magnificent testimonies to local history. Their illustrations provide insight into particular religious notions, myths and legends and thus into a past which is seldom referred to in the non-churchly historical narrative. The sub-form of the religious medal became wearable thanks to a loop or a punched hole. And these items definitely were being worn, sometimes around the neck, but much more often being sewed onto the hat or the clothes. They simultaneously served as visible proof of the piety of its wearer to the public eye and the believer’s self-assurance of the divine powers.

The Werner Jaggi Collection comprises mainly European gnadenpfennige from four centuries. They were consecrated to a very special saint or refer to a certain pilgrimage. In addition, they mirror how animated both piety and veneration of saints were in the Catholic territories in the post-Reformation era which provided the people with support and guidance in their life before the Enlightenment ushered in the modern era.

Germany

3057: St. Leonard of Noblat. Silver pendant, upright oval, signed AT. Bavaria, 18th cent., in the style of the Seel workshop. The saint under a panoply, with crozier and chains, flanking below the blessings both of Zacharias and of Benedict. Rev. St. Martin riding r., encountering a beggar on the way. 40.4 x 33.5 mm. About very fine. Estimate: 75 euros.

St. Leonard is still a well-known figure in Bavaria thanks to the colorful Leonardi rides as they are performed at regular intervals in more than 50 communities in Bavaria. He is invoked as Holy Helper since the 11th century and is responsible mainly for the cattle.

According to a biography written in the 11th century, St. Leonard was a contemporary of Clovis, King of the Merovingians. Young Leonard appealed to the king time and again to free prisoners. His miraculous signs – he is said to have made the chains of captives burst – convinced the king eventually. His attributes, the chains, hark back to this myth. His crozier he owned to the story that he had refused the episcopal dignity and preferred retreating in a cell as a hermit instead.

The adjacent blessing of Zacharius apotropaically averted first and foremost the plague, but also witchcraft and severe weather. It came often in combination with the blessing of Benedict which was particularly promoted by the Mettern Abbey, Lower Bavaria, after six women accused of witchcraft had declared in 1647 that they had not been able to do harm due to the powerful protection provided by the blessing of Benedict inside.

3157: Ebersberg, Cloister Church of St. Sebastian. Cast silver pendant, gilded. Augsburg(?), Late 17th / early 18th cent., of Philipp Heinrich Müller. Half-length portrait of St. Sebastian frontal, with two arrows in his garment. Rev. haloed half-length portrait of St. Ignatius of Loyola l., praised as founder of the Jesuits. Signature of the artist in the arm’s exergue. 25.1 mm. Peus Coll. cf. 439. Very rare. Fine to very fine. Estimate: 100 euros.

The history of Ebersberg as pilgrimage destination has been forgotten even by the people of neighboring Munich. The famous relic, though, i.e. a braincase of Sebastian, martyr and saint, which the first provost had brought with him after a trip to Rome during the 10th century, attracted thousands of pilgrims as late as Baroque times. The obverse of this gnadenpfennig is devoted to the patron saint of the church. The reverse is even more interesting, bearing the portrait of Ignatius of Loyola. His Jesuits were the spearhead of the Counter Reformation. In 1595, they had been appointed by William V, their big supporter, to replace the former Benedictine convent and strongly advertise the pilgrimage of St. Sebastian.

3161: Erding. Pilgrimage Church Holy Blood. Silver pendant, upright oval, end of 17th cent., in the style of the Salzburg workshop Seel. Suffering Christ with aureola and crown of thorns, from his five wounds blood is pouring that is collected in a bow standing on a piedestal decorated with an IHS emblem. Rev. bowl with soil piled up standing on the ground, with IHS emblem radiating above. 39.38 x 34.5 mm. Peus Coll. -. Och p. 162f., nr. 90. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 150 euros.

While the ‘Erdinger Weißbier’ is a trademark that is well-known worldwide, only very few people know that there once was a flourishing pilgrimage to Holy Blood. A statue of suffering Christ bore this name that is connected with a miracle of the host: a rich and a poor peasant went to attend Communion in 1417. On the way, the rich peasant told the poor one that he owed his entire wealth to a consecrated host which he kept in a chest. The poor peasant took that as an example. He intended to not swallow the host but to take it home as talisman for his own prosperity. Of course, everything went wrong: according to the earliest narrative, the host hovered out of the man’s mouth only to disappear in front of everybody. Later sources have it that the host had sunken into the ground – as depicted on our gnadenpfennig – , after which the pilgrimage church had been built as atonement. More important than the legend is the reason why it was so strongly advertised. Two matters at once could be addressed with it, in a popular way. Firstly, there was the ongoing discussion with the Reformed about the doctrine of transubstantiation. While the Catholics regarded the transforming host as the body of Christ (hence capable of such wonders and worshipped as suffering Saviour by the church in Erding), the Protestants disputed it vehemently. They saw the host not as the true holy but rather as a sign. At the same time, the story was ideally suited to be used in the official church’s preaching and her fierce fight against superstition sparked off by such consecrated objects. The message reads: suffering Christ was not willing at all to bow to talismans and magic.

3189: Taxa. Maria Stern Abbey. Cast silver pendant, upright oval of Philipp Heinrich Müller, Augsburg, 17th/18th cent. Above the cloister site, the destination of approaching pilgrims which are greeted at the gates by a large crucifix, an altar and flags, the miraculous image of Maria Stern is hovering. Below is the egg depicted, dividing the year 1618 inscribed on the tile, hence the start of the local pilgrimage. Rev. St. Nicholas of Tolentino kneeling in front of Virgin Mary with Child in the clouds, receiving a wreath from the Child; flanking the artist’s signature. Beierlein (Bayerische Klöster) I, 237. Very fine. Estimate: 150 euros.

In 1606, Hans Wilhelm Hundt (1560-1630), Lord of Sulzemoos and Odelzhausen, took a vow. When in distress at sea, he vowed that he would build a chapel in honor of Mother of God at once given he reached the shore safely. But when he did, he forgot the vow until a hen reminded him of his promise 10 years later. As we are told by the writing of the well-known itinerant preacher Abraham a Sancta Clara, bearing the interesting title ‘Gack, Gack, Gack, Gack, a Ga’, the hen laid a special egg on a brand-new tile that exhibited the depiction of Mother of God with the aureole.

Not just the representation on the obverse of our amulet recalls this miracle but the coat of arms (which is still in use) of the community of Odelzhausen, site of the associated chapel.

The city fathers could thank the hen because – as can be seen on the amulet – pilgrims came in great number from far and abroad to the community. The little chapel was replaced by the baroque pilgrimage church already in 1654, which the Discalced Augustinians took care of. This is the reason why St. Nicholas of Tolentino is depicted on the reverse of the amulet. He was the first Augustinian to be canonized. In 1446, Pope Eugene VI (likewise an Augustinian) could draw on as many as 300 miracles (including at least 3 resurrections from the dead). He was a saint to the liking of the Counter Reformation: he entered the Augustinian Order when he was 16 years old. Modest and beneficent in person, he used drastic descriptions of the penalties in the afterworld in order to proselytize the sinners. The visions he received from the purgatory were so impressive that Leo XIII announced him Patron of the Souls in the Purgatory in 1884. With the Augustinian Order likewise the cult of St. Nicholas of Tolentino was brought to Southern Germany where he is venerated as patron saint of Bavaria. The sermon of another Augustinian, the aforementioned Abraham a Sancta Clara, made the cloister of Taxa widely known, to the effect that the cloister over time possessed 184 acres of forest and assets amounting to 19,400 gulden. That of course aroused the state’s interest. In 1802, the cloister of Taxa was secularized; cloister and church were torn down.

You can find the complete auction catalogue on the Gorny & Mosch website.

The second part will present objects from Austria, Switzerland and Italy.