December 23, 2010 – Few countries have as many coins depicting John Paul II as Poland. And few themes appear as often in Poland’s numismatic production as the portrait of the Polish pope. There are commemorative coins on occasion of his papal trips to Poland and also on his visit to the United States; moreover, the “10th Anniversary of Pontificate” is celebrated with a coin and the 25th anniversary, to be sure, as well. Even the Pope as a pilgrim and the blessing Pope are numismatic motifs. His visit to Our Lady of Czestochowa was remembered with a coin and, needless to say, his death in 2005.

The Poles have an especially close relationship to this pontiff. In the following, we would like to shed a bit of light on this connection.

10 Zlotych 2002. Photo: Mint of Poland.

The Roman-Catholic Church in Poland

Being a member of the Roman-Catholic Church goes without saying for a lot of Poles. The Church is part of their national identity; over centuries, the country’s spirit of togetherness has defined itself through faith. An early example for this is the successful resistance of the fortified monastery of Czestochowa against the Protestant invaders in 1655 during the Swedish deluge. Victory was credited to the Black Madonna of the monastery of Jasna Gora mountain, which to the present day still is one of the most highly venerated icons of the country.

Roman-Catholic faith became a home for those Poles who came under the rule of monarchs of different faith. No wonder that voices calling for independence were much louder in those territories than in the part ruled by the Catholic Habsburg dynasty.

In the 20th century the Roman-Catholic Church repeatedly took on a prominent role in the struggle for independence – in part even armed – during World War I and against the terror of the Nazis. One-fourth of all Polish priests died in the resistance against German rule.

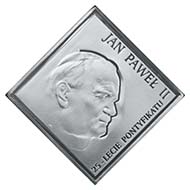

20 Zlotych 2003 on the occasion of the silver anniversary of the Pope’s ordination. Foto: Mint of Poland.

A Polish Biography

Karol Jozef Wojtyla was born on May 18, 1920, in Wadowice. He was from a poor family. Karol probably was just an ordinary child who liked playing soccer, swung the censer as an altar boy and studied well. In 1938, one year before the German invasion of Poland, he had enrolled in university. However, after occupying Poland the Germans closed all universities. Students and courageous lecturers went underground to operate a clandestine university – a dangerous undertaking. As many others, Wojtyla was arrested; however, he managed to avoid deportation to Germany.

Karol Wojtyla among friends in Cracow. Photo: Wikipedia.

In those years he entered the clandestine seminary of the Archdiocese of Krakow. On November 1, 1946, he was ordained a priest. Working as a pastor and, after receiving his doctorate, as a professor of theology and ethics Karol Wojtyla survived the Stalinist terror. In 1959 he was appointed an auxiliary bishop of Krakow. In this function he took part in the Second Vatican Council which would start the modernization of Catholic doctrine.

In 1964 Wojtyla became the Archbishop of Krakow. In continuous nonviolent resistance he demanded religious freedom for all Poles. His faithful flock experienced him as an undaunted fighter against communism. In Germany he became well-known for his efforts at initiating German-Polish reconciliation.

The Polish Pope

On October 16, 1978, Karol Wojtyla, previously regarded as an outsider, was elected the 264th pope by the conclave of 111 cardinals with 99 votes in the eighth ballot. He owed his election to the stalemate between the two leading (Italian) candidates and to the acclaim of the non-Italian cardinals who saw a chance to elect a non-Italian pope for the first time in almost 500 years.

Karol Wojtyla was the first Slav to become pope in history; besides, with only 58 years he was remarkably young.

The Pope’s second visit to Poland in 1987. Photo: Wikipedia.

The Visit to Poland

From the very beginning, the new pope revealed himself as an uncompromising fighter for freedom. As early as in 1979, only a few months after taking up office John Paul II traveled to his home country, following an invitation of the Polish government that had hoped to gain sympathy from the masses with this step. The invitation had been agreed on with Moscow, but the communist officials were shocked when they realized they had set off an avalanche.

10 million people, about one-fourth of the entire Polish population or – in other words – every second adult Pole attended the public appearances of John Paul II. Thus, the Pope became a symbol of resistance against communism and attending his visit a political manifesto. Lech Walesa, then leader of the Solidarity workers’ movement, later would say that John Paul II had awakened the country when encouraging all Poles to forget about their fears.

Solidarity

On August 14, 1980, the 17,000 workers of the Gdansk Lenin shipyard went on strike, led by Lech Walesa. Soon, the resistance spread throughout the country. The whole world was waiting to see how the Soviet Union would react. On December 7, John Paul II was informed by American President Jimmy Carter that the Soviet Union apparently was planning to invade Poland. A good week later, John Paul II directly contacted Brezhnev, comparing the Soviet Union to the troops of the Nazis that once occupied his home country. We will never know whether it was the pope’s threat to inflame public opinion that made the Soviet leaders refrain from military intervention. After all, the invasion of Poland did not materialize.

As early as January 15, 1981, John Paul II received a delegation from Solidarity led by Lech Walesa at an audience in the Vatican. The moral support from the head of the Catholic Church with the Polish people who were thirsting for freedom played a part no to be underestimated – contributing to the destabilization of the Polish government and the perseverance of the Solidarity movement leaders.

The Assassination Attempt

Possibly, that was the reason for the assassination attempt committed by the Turkish right-wing extremist Mehmed Ali Agca on May 13, 1981. In 2006, an Italian investigation committee found out in 2006 that the attempt on the pope’s life had been planned by Russian intelligence in cooperation with the Bulgarian secret service. The Polish communists seem to have known nothing of it.

A few months later, in December 1981, martial law was declared in Poland. The Church remained the only organization where there still was some scope for resistance. Its decisive role in everyday life also had to do with the fact that it was allowed to distribute relief supplies from the West, mainly from Germany, among the needy population.

A Fighter Against Communism

On his 104 papal trips, John Paul II repeatedly visited Poland. In 1983, on his second trip to Poland, the Pope again met Lech Walesa, although the union leader in effect was under houses arrest and Solidarity meanwhile had been banned.

On another visit in 1987 he appealed to the government to respect human rights and lift the ban on Solidarity. No pope of modern times had ever interfered to that extent in political affairs. In fact, the Vatican State seems to have participated in the funding of the Polish resistance movement. Today, it is generally assumed that John Paul II arranged that the Polish resistance be financially supported by the Americans.

In 1989 the turning point had come. It was widely accepted that John Paul II played an important part in the fall of communism. He even received a piece of the Berlin wall as a gift, which can be seen in the Vatican Gardens today.

However, the Pope remained closely linked to Poland when it was free again, visiting his native country another five times – in 1991, 1995, 1997, 1999 and 2002. It was a programmatic decision that John Paul II canonized the Polish nun Mary Faustyna Kowalska as the first saint of the new millennium.

10 Zlotych 2005 on the occasion of the Pope’s death. Photo: Mint of Poland.

A Polish Saint?

When John Paul II died, on April 2, 2005, the whole country was in mourning. Rumors ran that the Pope had wished to be buried in Poland, his native country. Until the present day, the Polish Church hopes to secure the papal heart for Warsaw. In his will, in fact, the Pope left the decision about his burial to be taken by the College of Cardinals, which – until now – has not yet decided on that option.

3.5 millions of pilgrims attended the requiem mass for John Paul II in Rome, among them a vast multitude of Poles. Not even half a year later, the process of his beatification was initiated. This cause is being pursued with great urgency, unrivaled by any other previous beatification. Since December 19, 2009, John Paul II is called “Venerable Servant of God”, which is the step prior to beatification.

Addendum: Roman-Catholic Faith and Religious Freedom

An internal survey by the Polish episcopate reveals that religious devotion in Poland has radically declined since the overthrow of the communist regime. The number of churchgoers has dropped by up to one-third – mainly in the big cities. Notwithstanding, in Poland the percentage of practicing Catholics is still higher than in any other European country.

If you want to see film on the Pope’s visits to Poland, click here.