by Ursula Kampmann

August 4, 2011 – Today’s stage takes us to several highlights of the journey: a peak of kindness in Pydna, a touristic highlight in the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki and a climax of the fight about the Greek austerity package…

Day 16, June 25, 2011, Pydna or: the end of the Macedonian Empire

Pydna – everyone dealing with ancient history is familiar with that name. It was here where the decisive battle between the Roman and the Macedonian armies took place on June 22, 168. According to Livy, 20,000 Macedonians lost their lives. Defeated King Perseus managed to escape but forfeited. Macedonia, rich in mineral resources, was liquidated by the Romans. What was left was a humiliated population which was barely able to support itself.

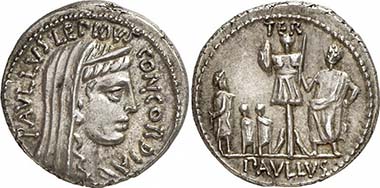

L. Aemilius Paullus. Denarius, 62. Concordia. Rev. Aemilius Paullus with trophy, captured Perseus with his sons in front of it. Gorny & Mosch 191 (2010), 1981.

Pydna, however, had a much longer history. The coastal city was founded in the 6th cent. B. C. Thanks to its easily accessible location it exported Macedonian raw materials and consequently became rich. Starting from Pydna, countless ships, mainly transporting building timber, sailed north to the big commercial centers. Themistocles from Athens, for example, found himself a ship here that brought him to Ephesos. The Macedonian kings and the Athenians would have been only too pleased to get Pydna under their control. But only Philipp II managed to integrate it into his empire successfully. Under Roman dominion, Pydna carved out its existence as provincial city.

Byzantine basilica of Kitros, ancient Pydna. Photograph: KW.

As testified by archaeological finds, a port was built in Byzantine times, close to the ancient city, with a basilica of which remains are extant. The archaeological excavation is not only accessible to the public but tidy and well-kept. This is accomplished by an individual who asks politely every person visiting ‘his’ excavation site if ones manages without any assistance or rather wishes to be guided – for free, of course (and he means it!). Subsequently, he asked for an entry in the guestbook to convince the administration of the importance of ‘his’ excavation.

Vista from the basilica to the sea. Photograph: KW.

I am angry with myself that I didn’t ask his name and didn’t take a photograph of him because I would like to thank him personally for his magnificent effort. It was a pleasure to get to know someone like him, so dedicated and doing all he could. People like him give Greece a friendly face.

The Frankish fountain in the Byzantine basilica. Photograph: KW.

Back to Byzantine Kitros. It flourished at the beginning of the 13th century, when, in 1204, the crusader’s army under Venetian leadership brought down the Byzantine emperor. That made Greece, which was formerly ruled by Constantinople, subject to negotiation. A Frankish army besieged and seized Kitros, burnt the city to the ground and established a fortress in the former basilica whose fountain well is preserved which had been drilled at that time.

Traces of lead in a column shaft. Photograph: KW.

Although the archaeological excavation of Kitros isn’t as significant as other sites in Macedonia, the one with eyes open discovers interesting things nonetheless. Like traces of lead in the remains of a column as it was used in antiquity to fix columns shafts flexibly.

Day 17, June 27, 2011, Thessaloniki: Archaeological Museum

We stayed in Platamon for an entire week. Now the time has come to move on. Destination is Thesaloniki, second largest city of Greece. Approximately one million people live in the city and its surroundings. Thessaloniki is renowned for its high number of Byzantine churches with their mosaic decoration being much better preserved than in Constantinople, capital proper.

Thessaloniki. Bronze, 187-31. Hermes. Rev. Pan with lagobolon. From Münzen & Medaillen Deutschland 30 (2009), 184.

Founded by Kassandros in 315 B. C., who named the new city after his wife Thessalonike – half-sister of Alexander the Great –, Thessaloniki soon became one of the most important harbors in Macedonia thanks to its easily accessible location.

Thessaloniki. Augustus. Bronze, c. 17 B. C. Head of Augustus. Rev. laurel wreath with city name. From auction Lanz 151 (2011), 677.

After the victory of the Romans, its importance increased still. In 146 B. C., the Romans had built the strategically so important Via Egnatia, artery between the Adriatic coast and the Bosporus. Thus every significant of insignificant Roman passed Thessaloniki on the way to Asia Minor, whether his name was Cicero or Paulus…

Maximianus Herculius. Argenteus, Thessaloniki, 302. Rev. Storehouse door. From auction Lanz 135 (2007), 932.

No wonder, then, that Thessaloniki became an important center of administration that got its own, well-frequented mint under the Tetrarchs. Galerius even extended the city as his residence. After Constantine, by contrast, it became slightly less important because Constantinople took over the role of a center in the East. Nevertheless, the Thessaloniki Mint continued its production. And the people got along well with their role of living in the second most significant city of the Byzantine Empire.

Yolande de Montferrat. Bulla, 1285-1317. In 1285, Yolande married Byzantine Emperor Andronikos II, but from 1303 onwards she stayed in Thessaloniki at all times where she pursued her own politics. From auction Lanz 144 (2008), 815.

When Constantinople was conquered in 1204, that changed. First, Thessaloniki became capital city of a Frankish kingdom unter Boniface of Montferrat. Then, the Despot of Epirus assumed power and got himself crowned as counter-emperor there. Thessaloniki became the new capital. That empire ended in 1246, when it was conquered by John III. His grandson managed in 1261, to take Constantinople from the Franks, too.

Ottomans. Mohammad V, 1909-1918. 10 Kurusch 1909, Thessaloniki Mint. On his visit to the city. From auction Gorny & Mosch 143 (2005), 5536.

In 1430, Murat II conquered Thessaloniki. It became part of the Ottoman Empire. The city flourished under Turkish rule. It continued to be an important commercial center and experienced a boom with the industrialization. A fire in 1890 not only made 20,000 people homeless but destroyed precious, partly ancient, structure. The damage, however, was soon repaired. Thessaloniki was regarded a wealthy, vibrant and intellectually very lively city. Corresponding to that, it was here where the Young Turk Revolution under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal, later Atatürk, began in 1908. Thessaloniki came to Greece only in the course of the shooting wars in the preliminary stages of World War I. The city, which was right in the middle of things, experienced bad times then. A major part of the refugees after the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) found a new home here, which made the Greek population in Thessaloniki become the majority for the first time again since antiquity.

Archaeological Museum in Thessaloniki. Photograph: KW.

First, we went to the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki. It is hard to think of a better start. The material housed here keeps up with the best museums of the world. Apart from the famous gold department a splendid exhibition of finds from Thessaloniki has been set up in the previous years.

A rare find: the eye of a goddess with glass inlays. Photograph: KW.

The first surprise was a special exhibition on glass. I was particularly fascinated by an eye of a monumental statue, made of glass with bronze eyelashes.

Gold of the Macedonians. Photograph: KW.

Part of the permanent exhibition is a presentation of the unparalleled gorgeous gold items that had been found in Macedonia. The visit is a must to realize how incredibly rich in precious metals this country was.

Gold wreath in the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki. Photograph: KW.

The Vergina finds are put in a perspective by that since not every gold wreath is likely to have decorated the head of a Macedonian king once – there are simply too many of them.

Macedonian coins. Photograph: KW.

Detailed information is provided on the Macedonian coinage. Big explanatory boards on mining, metal deposits and metal working preface the exhibition.

One of the medallions of the Egyptian find of Abukir. Photograph: KW.

Near Abukir in Egypt a hoard of gold medallions was found in 1902 of which two show Macedonian Olympias. Back then, the Thessaloniki Museum was able to acquire one of these. It is on display in the exhibition. (By the way, the other one is in Berlin.)

Gold pattern or cast after a tetradrachm from Akanthos. Photograph: KW.

It’s a mystery to me (and I couldn’t get close enough to solve it) if this magnificent gold piece is a cast after a tetradrachm from Akanthos or a pattern.

Famous Derveni Krater. Photograph: KW.

In 1962, this gorgeous mixing vessel was discovered in a tomb in Derveni, not far from Thessaloniki. It is made of gilded bronze, weighs 40 kilos and served in a final step as urn of the Thessalian nobleman Astiouneios from Larisa, son of Anaxagoras. His and his wife’s remains rested still in it when it was unearthed.

Detail of the Derveni Krater. Photograph: KW.

Depicted is the divine couple Dionysos and Ariadne, accompanied by maenads and satyrs. One can’t stop looking at it – in doing so, one gets pulled deeper and deeper into the depictions on this incredibly artistic piece.

Volute of the Derveni Krater. Photograph: KW.

Research disagrees as to when and where this art work was made. Some favor 350 B. C. and Thessaly, when the Aleuads, the big opponents of the tyrants of Pherai, were in power. Others consider a royal bronze smith of Philipp its father who created the showpiece between 330 and 320 B. C.

Sling lead – testimonies to the campaigns of Philipp II. Photograph: KW.

Apart from the gold exhibition, there is a magnificent gallery on Greek daily-life. Topics are war, trade and economy, house and family as well as burial customs.

Showcase in the room devoted to trade and economy. Photograph: KW.

In the room devoted to trade and economy numismatic objects as well as coins, weights and seals can be found.

Marble door of a sepulchral monument. Photograph: KW.

And here are just a few of the highlights that caught my eye – of course that doesn’t cover everything worth seeing in the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki. If you ever get the chance of visiting it make sure to take your time over it.

Plaster cast of a deceased’s face for the production of a death mask. Photograph: KW.

This mask, for example, is quite unusual. Surely, it is widely known that the Roman nobility had masks taken from their deceased ones from which portraits for private use were made but I have never seen an original mould before.

Archaic temple on Roman foundations. Photograph: KW.

Another surprise is provided by this Archaic temple from the 6th cent. which, according to its context, was made in Roman times. Yes, you’ve read right. Here we are faced with the rare of a case of temple relocation: the old temple of Aphrodite of Aineia was brought to Thessaloniki to serve the cult of Julius Cesar there.

Traces of protest: German chancellor Angela Merkel as vampir. Photograph: KW.

I don’t know how many hours we spent in the Archaeological Museum. Anyway, afterwards, we only had one thing in mind: to eat and drink something. We went into the city center where we (finally) come across traces of the protests against the austerity package that came to vote on June 29, 2011, in parliament. After the horrible pictures taken on Syntagma Square reality was rather modest. Just a few depictions of Mrs Merkel with elongated canines…

Protesters at the White Tower. Photograph: KW.

…and a camp site with protest signs at the White Tower. That was it. The demonstration was peaceful, and we didn’t notice any of the hostility against Germans evoked by the media. On the contrary, we had some nice talks in the tavern where we dined. Greeks are usually amazed when someone can read their writing (and they can’t make sense of someone reading their writing but not speaking their language). That was the opening to some interesting information. The worst thing for many young people surely is hopelessness. They had studied, and now they want a good job after long years of deprivation – economy, however, doesn’t need them or isn’t willing to pay for their efforts adequately. This happens whether your field of study was business administration, law, engineering or something of real importance to economy like archaeology.

Days 18/19 Tag, June 28-29, 2011, Thessaloniki

Let’s summarize the two days in Thessaloniki.We had found ourselves quarters in Panorama which is as beautifully situated as its name suggests, high above the city. The bus takes you directly to the old town. This is the perfect solution for getting there. Returning by public transport, by contrast, was a different thing – we were successful only at our third attempt. You see, the buses take a different route back, through the city center, and that may be something of a puzzle to a tourist.

Be that as it may, when we were standing in the bus, the driver addressed us in perfect German, with a slight Lower Rhenish accent. He used to work in Germany and really enjoyed applying his familiarity once again. Of course, we instantly were right in the middle of a lively discussion about the crisis. To him, the current situation was mainly due to two reasons: the unfairness of the Greek tax system that doesn’t even provide an incentive to being honest. Plus the fact that in Greece everybody wants to be boss immediately; and skilled manual work is ill-reputed. He had sent his daughter back to Germany for there ought to be a future for her…

Part of the unearthed Palace of Galerius. Photograph: KW.

The first thing we discovered in the morning during our walk was parts of the Palace of Galerius whose archaeological excavation is continually integrated into the cityscape.

Excavation in another part of the Place of Galerius. Photograph: KW.

There were even archaeological excavations conducted in another part of the Palace of Galerius.

Gathering to demonstrate in front of the Arch of Galerius. Photograph: KW.

Looking at the Arch of Galerius thoroughly was more difficult for were many students who gathered there to protest. Don’t get me wrong: it wasn’t aggressive at all. No one objected at us approaching and taking pictures, but it was terribly noisy while “Bella Ciao” blasted out of the loudspeakers.

Detail of the Arch of Galerius: sacrifice within the family circle. Photograph: KW

The arch was erected after the victory of Galerius in 298. It displays details in abundance – mainly of the campaign historians love to use as source because they lack other information.

Divus Galerius. Follis, 311, Thessalonika. Rev. sepulchral building with dome roof, eagle above. From auction Lanz 109 (2002), 841.

At roughly 100m distance to the Arch of Galerius there is the “Rotunda”, a building Galerius had erected in 360 A. D. which was probably intended as his tomb.

Rotunda of Galerius: an impressive building. Photograph: KW.

After his death, however, he was buried in Felix Romuliana (present-day Serbia). The Rotunda stood empty and was rebuilt by Constantine to become a church. The high-quality mosaics whose remains we marveled at in the Rotunda date to that time. When the Ottomans conquered the city, the building became a mosque with a minaret that still stands and was even renovated in 2004 even though the Greek Orthodox Clergy tries to convert it into a church again from time to time.

Mosaic remains in the Rotunda’s cupola from the 4th cent. A. D. Photograph: KW.

After all, many people consider the building the most ancient Christian Church of the world, albeit there are many candidates to that title. All the same…

Church of St. Demetrios. Photograph: KW.

Thessaloniki has interesting churches in abundance. We didn’t visit every single one. As to the ones we’ve been to, it would be boring top report in detail one after the other even though their foundation date to late imperial times and/or have wonderful mosaics.

Let’s stick to two: firstly, the one of St. Demetrios, and, secondly, the one of Hagia Sophia.

Alexios I Komnenos. Aspron Trachy, Thessaloniki, 1082-1087. Rev. St. Demetrios and emperor. From auction Peus 401 (2010), 756. Photograph: KW.

The earliest written sources on St. Demetrios date to the 9th cent. They tell of him being killed in Thessaloniki in the course of the persecution of Christians under Diocletian. Perhaps that tradition originated in a local martyr cult because archaeological finds in the church point to Demetrios being venerated there as early as the middle of the 5th cent. The relics were discovered later. By that time, the saint had already become patron saint of Thessaloniki – and motif for the coins.

Interior of the Church of St. Demetrios. Photograph: KW.

The first church building harks back on a private foundation of 412/3. The present-day basilica is located on the foundation of a building from the second half of the 5th cent. Unfortunately, much had to be repaired after a big fire in 1917, so that that are only a few mosaics and the magnificent columns in the nave left indicative of how old this building actually is.

Reliquiary shrine for the bones of St. Demetrios. Photograph: KW.

The bones lying in the reliquiary shrine have been found as late as the 7th cent. Much to the disgust of the local bishop John, by the way, who publicly voiced his doubts about their authenticity.

Center of the cult of Demetrios; the sacred oil was bottled here. Photograph: KW.

The bones are said to have proven their authenticity by oozing a kind of smelling liquid incense. That was skimmed at regular intervals…

Bottle for the sacred oil with a picture of St. Demetrios. Photograph: KW.

One reason was to prevent the sarcophagus from brimming over, the other to distribute the oil amongst the pilgrims (most probably for a generous donation). By the way, the oil allegedly still continues to pour.

Find coins from the crypt where today a museum is located. Photograph: KW.

All this takes place in the crypt, underneath the church. A small museum is located there, too, with Byzantine reliefs, ceramics and a number of coin finds as well.

Protesters in front of the Church of Demetrios. Photograph: KW.

While we visited the church, a demonstration of the unions against the austerity packages was conducted. It was peaceful and by no means seemed threatening. After the end of the demonstration we met the participants, who sat in the Cafés around the pedestrian zone.

Policemen on stand by. Photograph: KW.

It is very likely that the calm actions of the police contributed to the de-escalation. The stayed in the side streets and appeared rather relaxed, having put aside helmets and shields, sitting on the pavement, kidding and eating their packed lunches.

Greek agora of Thessaloniki. Photograph: KW.

The many remains of the Greek agora are likewise integrated into the cityscape. The Thessaloniki Mint allegedly was located here.

Hagia Sophia of Thessaloniki. Photograph: KW.

The church of Hagia Sophia, dating to the 8th cent., is particularly interesting because it is one of the few buildings from the time of the iconoclasm and survived until the present day. It is based on the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, of course.

Ceiling mosaic in the church of Hagia Sophia from the end of the 9h cent. Photograph: KW.

The gorgeous mosaic on the ceiling dates to the 9th cent. and hence to the time immediately following the iconoclastic era. It shows the Ascension of Jesus Christ in the circle of the apostles and Mary.

Capitel with acanthus leaves -‘gone with the wind’-style. Photograph: KW.

This chapter it surely not that remarkable to be absolutely shown here, but I couldn’t resist pointing at a local leaflet about the Byzantine buildings of Thessaloniki referring to these acanthus leaves as ‘gone with the wind’.

Byzantine city wall. Photograph: KW.

Thessaloniki is quite an arduous city, particularly when one doesn’t confine oneself to the attraction of the lower town but ascends to the upper town where not only a number of Byzantine churches are situated but very well-preserved fortification walls with towers and gates as well. Parts thereof were used until the 19th century. In the topmost part, the so-called “Heptapyrgion” (= Seven Towers), the Ottoman garrison stayed. After the buildings served as prison until 1989 where many political prisoners were kept mainly in the 20th century, the University is located here now.

View at Thessaloniki from the upper town. Photograph: KW.

In contrast to the upper town where many small, old houses have survived of which are restored for the major part today, the lower town is characterized by multistoried, modern buildings.

There was, of course, no chance to refer to everything we have seen in Thessaloniki. Otherwise this issue would have been much longer. Having spent two and a half days in the city, we naturally have only seen a fraction of all worth a visit. At any rate, Thessaloniki is a highlight of Macedonia, not only thanks to its unique Archaeological Museum but also to its many nice, open-mined people we have met here.

That will do for now. Don’t miss the next issue of the numismatic diary. The journey takes us to Chalkidiki as base camp for trips to places where some of the most beautiful coins of human history were produced. I just say two words: Amphipolis and Olynthos.

Anyone who would like to see the treasures of Northern Greece with his own eyes might be interested in a tour I will be guiding in autumn, on behalf of Klingenstein. For more information please click here (available in German only).

You can read all other parts of this diary here.